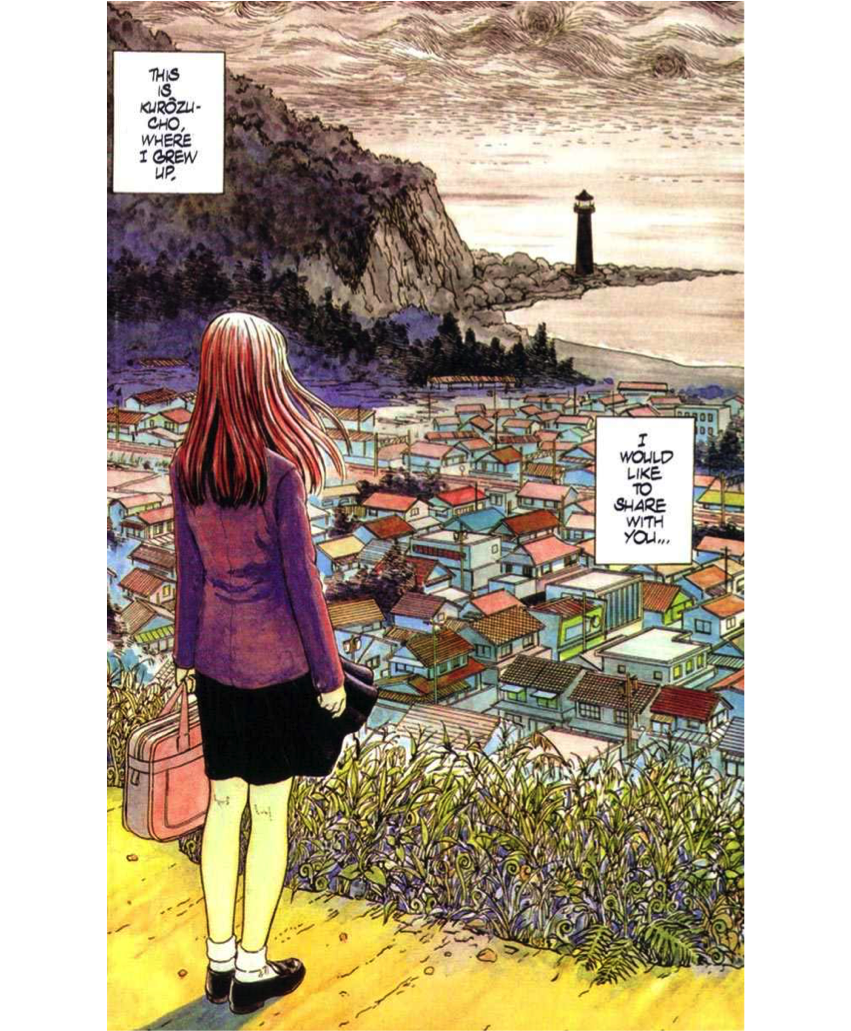

I

It was not until five weeks after his father’s funeral that Henry Farange was able to remove the white plastic milk crate containing the old man’s final effects from the garage. His reticence was a surprise: his father had been sick—dying, really—for the better part of two years and Henry had known it, had known of the enlarged heart, the failing kidneys, the brain jolted by mini-strokes. He had known it was, in the nursing home doctor’s favorite cliché, only a matter of time, and if there were moments Henry could not believe the old man had held on for as long or as well as he had, that didn’t mean he expected his father to walk out of the institution to which his steadily-declining health had consigned him. For all that, the inevitable phone call, the one telling him that his father had suffered what appeared to be a heart attack, caught him off-guard, and when his father’s nurse had approached him at the gravesite, her short arms cradling the milk crate into which the few items the old man had taken with him to the nursing home had been deposited, Henry’s chest had tightened, his eyes filled with burning tears. Upon his return home from the post-funeral brunch, he had removed the crate from his backseat and carried it into the garage, where he set it atop his workbench, telling himself he couldn’t face what it contained today, but would see to it tomorrow.

Tomorrow, though, turned into the day after tomorrow, which became the day after that, and then the following day, and so on, until a two week period passed during which Henry didn’t think of the white plastic milk crate at all, and was only reminded of it when a broken cabinet hinge necessitated his sliding up the garage door. The sight of the milk crate was a reproach, and in a sudden burst of repentance he rushed up to it, hauled it off the workbench, and ran into the house with it as if it were a pot of boiling water and he without gloves. He half-dropped it onto the kitchen table and stood over it, panting. Now that he let his gaze wander over the crate’s contents, he could see that it was not as full as he had feared. A dozen hardcover books: his father’s favorite Henry James novels, which, he had claimed, were all that he wanted to read in his remaining time. Henry lifted them from the crate one by one, glancing at their titles. The Ambassadors. The Wings of the Dove. The Golden Bowl. The Turn of the Screw. What Maisie Knew. He recognized that last one: the old man had tried twice to convince him to read it, sending him a copy when he was at college, and again a couple of years ago, a month or two before he entered the nursing home. It was his father’s favorite book of his favorite writer, and, although he was no English scholar, Henry had done his best, both times, to read it. But he rapidly became lost in the labyrinth of the book’s prose, in sentences that wound on for what felt like days, so that by the time you arrived at the end, you had forgotten the beginning and had to start over again. He hadn’t finished What Maisie Knew, had given up the attempt after chapter one the first time, chapter three the second, and had had to admit his failures to his father. He had blamed his failures on other obligations, on school and work, promising he would give the book another try when he was less busy. He might make good his promise yet: there might be a third attempt, possibly even success, but when he was done, his father would not be waiting to discuss it with him. Henry removed the rest of the books from the crate rapidly.

Here was a framed photo of him receiving his MBA, a smaller black and white picture of a man and woman he recognized as his grandparents tucked into its lower right corner. Here was a gray cardboard shoebox filled with assorted snapshots that appeared to stretch back over his father’s lifetime, as well as four old letters folded in their original envelopes. Here was a postcard showing the view up the High Street to Edinburgh Castle. Here was the undersized saltire, the blue and white flag of Scotland, he had bought for his father when he had stopped off for a weekend in Edinburgh on his way home from Frankfurt, just last summer. Here was a cassette tape wrapped in a piece of ruled notebook paper bound to it by a thick rubber band, his name written on the paper in his father’s rolling hand.

His heart leapt, and Henry slid the rubber band from the around the paper with fingers suddenly dumb. There was more writing on the other side of the paper, a brief note. He read, “Dear Son, I’m making this tape just in case. Listen to it as soon as possible. It’s all true. Love, Dad.” That was all. He turned the tape over: it was plain and black, no label on either side. Leaving the note on the table, he carried the tape into the living room, to the stereo. He slid the tape into the deck, pushed PLAY, adjusted the volume, and stood back, arms crossed.

For a moment, there was only the hum of blank tape, then a loud snap and clatter and the sound of his father’s voice, low, resonant, and slightly graveled, the way it sounded when he was tired. His father said, “I think I have this thing working. Yes, that’s it.” He cleared his throat. “Hello, Henry, it’s your father. If you’re listening to this, then I’m gone. I realize this may seem strange, but there are facts of which you need to be aware, and I’m concerned I don’t have much time to tell you them. I’ve tried to write it all down for you, but my hand’s shaking so badly I can’t make any progress. To tell the truth, I don’t know if the matter’s sufficiently clear in my head for me to write it. So, I’ve borrowed this machine from the night-duty nurse. I suppose I should have told you all this—oh, years ago, but I didn’t, because—well, let’s get to what I have to say first. I can fill in my motivations along the way. I hope you have the time to listen to this all at once, because I don’t think it’ll make much sense in bits and pieces. I’m not sure it makes much sense all together.

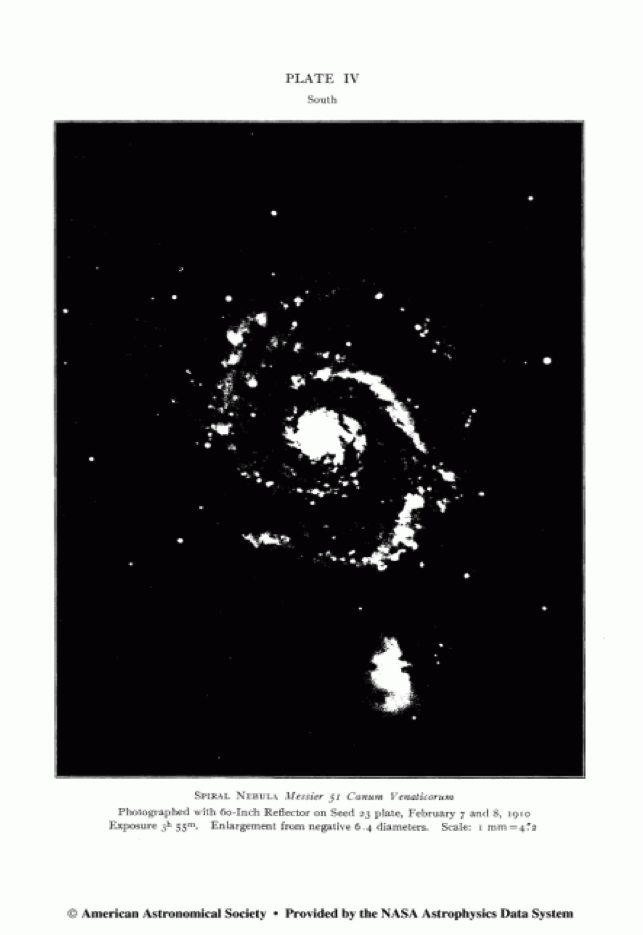

“The other night, I saw your uncle on television: not David, your mother’s brother, but George, my brother. I’m sure you won’t remember him: the last and only time you saw him, you were four. I saw him, and I saw his butler. You know how little I sleep these days, no matter, it seems, how tired I am. Much of the time between sunset and sunrise I pass reading—re-reading James, and watching more television than I should. Last night, unable to concentrate on What Maisie Knew any longer, I found myself watching a documentary about Edinburgh on public television. If I watch PBS, I can convince myself I’m being mildly virtuous, and I was eager to see one of my favorite cities, if only on the screen. It’s the city my parents came from; I know you know that. Sadly, the documentary was a failure, so spectacularly insipid that it almost succeeded in delivering me to sleep a good three hours ahead of schedule. Then I saw George walk across the screen. The shot was of Prince’s Street during the Edinburgh festival. The street was crowded, but I recognized my brother. He was slightly stooped, his hair and beard bone-white, though his step was still lively. He was followed by his butler, who stood as tall and unbending as ever. Just as he was about to walk off the screen, George stopped, turned his head to the camera, and winked, slowly and deliberately.

“From the edge of sleep, I was wide awake, filled with such fear my shaking hands fumbled the remote control onto the floor. I couldn’t muster the courage to retrieve it, and it lay there until the morning nurse picked it up. I didn’t sleep: I couldn’t. Your uncle kept walking across that screen, his butler close behind. Though I hadn’t heard the news of his death, I had assumed he must be gone by now. More than assumed: I had hoped it. I should have guessed, however, that George would not have slipped so gently into that good night; indeed, although he’s just this side of ninety, I now suspect he’ll be around for quite some time to come.

“Seeing him—does it sound too mad to say that I half-think he saw me? More than half-think: I know he saw me. Seeing my not-dead older brother walk across the screen, to say nothing of his butler, I became obsessed with the thought of you. Your uncle may try to contact you, especially once I‘m gone, which I have the most unreasonable premonition may be sooner rather than later. Before he does, you must know about him. You must know who, and what, he is. You must know his history, and you must know about his butler, about that…monster. For reasons you’ll understand later, I can’t simply tell you what I have to tell you, or perhaps I should say I can’t tell you what I have to tell you simply. If I were to come right out with it in two sentences, you wouldn’t believe me; you’d think I had suffered one TIA too many. I can’t warn you to stay away from your uncle and leave it at that: I know you, and I know the effect such prohibitions have on you; I’ve no desire to arouse your famous curiosity. So I’m going to ask you to bear with me, to let me tell you about my brother I what I think is the manner best-suited to it. Indulge me, Henry, indulge your old father.”

Henry paused the tape. He walked out of the living room back into the kitchen, where he rummaged the refrigerator for a beer while his father’s words echoed in his ears. The old man knew him, all right: his “famous” curiosity was aroused, enough that he would sit down and listen to the rest of the tape now, in one sitting. His dinner date was not for another hour and a half, and, even if he were a few minutes late, that wouldn’t be a problem. He smiled, thinking that despite his father’s protestations of fear, once the old man warmed up to talking, you could hear the James scholar taking over, his words, his phrasing, his sentences, bearing subtle witness to a lifetime spent with the writer he had called “the Master.” Henry pried the cap off the beer, checked to be sure answering machine was on, switched the phone’s ringer off, and returned to the living room, where he released the PAUSE button and settled himself on the couch.

His father’s voice returned.

II

Once upon a time, there was a boy who lived with his father and his father’s butler in a very large house. As the boy’s father was frequently away, and often for long periods of time, he was left alone in the large house with the butler, whose name was Mr. Gaunt. While he was away, the boy’s father allowed him to roam through every room in the house except one. He could run through the kitchen; he could bounce on his father’s bed; he could leap from the tall chairs in the living room. But he must never, ever, under any circumstances, go into his father’s study. His father was most insistent on this point. If the boy entered the study…his father refused to say what would happen, but the tone of his voice and the look on his face hinted that it would be something terrible.

That was how the story used to begin, as if it were a fairy tale that someone else had written and I just happened to remember. I suppose it sounds generic enough: the traditional, almost incantatory, beginning; the nondescript boy, father, butler, and house. Do you remember the first time I told it to you? I don’t imagine so: you were five, although you were precocious, which was what necessitated the tale in the first place. You were staying with me for the summer—your mother and her second husband were in Greece—in the house in Highland. That house! all those rooms, the high ceilings, the porch with its view of the Hudson: how I wish you didn’t have to sell it to afford the cost of putting me in this place. I had hoped you might choose to live there. Ah well, as you yourself said, what use is a house of that size to you, with no wife or family? Another regret…

But I was talking about the story, and the first time you heard it. Like some second-rate Bluebeard, I had permitted you free access to every room in the house save one: my study, which contained not the head of my previous wife (if only! sorry, I know she’s your mother), but extensive notes, four years’ worth of notes towards the book I was about to write on Henry James’s portrayal of family relations. Yes, yes, I should have known that declaring it forbidden would only pique your interest; it’s one of those mistakes you not only can’t believe you made, but that seems so fundamentally obvious you doubt whether in fact it occurred. The room was kept locked when I wasn’t working in it, and I believed it secure. All this time later, I have yet to discover how you broke into it. I can see you sitting in the middle of the hardwood floor, four years’ work scattered and shredded around you, a look of the most intense concentration upon your face as you dragged a pen across my first edition of The Wings of the Dove. I’m not sure how, but I remained calm, if not quite cheerful, as I escorted you from my study up the stairs to your bedroom. I sat you on the bed and told you I had a story for you. You were very excited: you loved it when I told you stories. Was it another one about Hercules? No, it wasn’t; it was another kind of story. It was the story of a little boy just about your age, a little boy who had opened a door he was not supposed to.

Then and there, my brain racing, I told you the story of Mr. Gaunt and his terrible secret, speaking slowly, deliberately, so that I would have time to shape the next event. Does it surprise you to hear that the story has no written antecedent? It became such a part of our lives after that. It frightened you out of my study for the rest of that summer; you avoided that entire side of the house. Then the next summer, when your friend Brad came to stay for the weekend and the three of us stayed up late while I told you stories, you actually requested it. “Tell about Mr. Gaunt,” you said. I can’t tell you how shocked I was. I was shocked that you remembered: children forget much, and it’s difficult to predict what will lodge in their minds; plus you had been with your mother and husband number two without interruption for almost nine months. I was shocked, too, that you would want to hear a narrative expressly crafted to frighten you. It frightened poor Brad; we had to leave the light on for him, which you treated with a bit more contempt than really was fair.

After that: how many times did I tell you that story? Several that same summer, and several every summer for the next six or seven years. Even when you were a teenager, and grew your hair long and refused to remove that denim jacket that you wore down to an indistinct shade of pale, even then you requested the story, albeit with less frequency. It’s never gone that far from us, has it? At dinner, the visit before last, we talked about it. Strange that in all this time you never asked me how I came by it, in what volume I first read it. Perhaps you’re used to my having an esoteric source for everything and assume this to be the case here. Or perhaps you don’t want to know: you find it adds to the story not to know its origin. Or perhaps you’re just not interested: literary scholarship never has been your strong point. That’s not a reproach: investment banking has been very good for and to you, and you know how proud I am of you.

There is more to the story, though: there is more to every story. You can always work your way down, peel back the layers ‘til you discover, as it were, the skull beneath the skin. Whatever you thought about the story’s roots, whatever you would answer if I were to ask you where you thought I had plucked it from, I’m sure you never guessed that it grew out of an event that occurred in our family. That donnee, as James would’ve called it, involved George, George and his butler and Peter, George’s son and your cousin. Yes, you haven’t heard of Peter before: I haven’t ever mentioned his name to you. He’s been dead a long time now.

You met George when you were four, at the house in Highland. I had just moved into it from the apartment in Huguenot I occupied after your mother and I separated. George was in Manhattan for a couple of days, doing research at one of the museums, and took the train up to spend the afternoon with us. He was short, stocky verging on portly, and he kept his beard trimmed in a Vandyke, which combined with his deep-set eyes and sharp nose lent him rather a Satanic appearance: the effect, I’m sure, intended. He wore a vest and a pocket watch with which you were fascinated, not having seen a pocket watch before. Throughout the afternoon and into the evening, you kept asking George what time it was. He responded to each question by slowly withdrawing the watch from his pocket by its chain, popping open its cover, carefully scrutinizing its face, and announcing, “Why, Hank,” (he insisted on calling you Hank; he appeared to find it most amusing), “it’s three o’clock.” He was patient with you; I will grant him that.

After I put you to bed, he and I sat on the back porch looking at the Hudson, drinking Scotch, and talking, the end result of which was that he made a confession—confession! it was more of a boast!—and I demanded he leave the house, leave it then and there and never return, never speak to me or communicate in any way with me again. He didn’t believe I was serious, but he went. I’ve no idea how or if he made his train. I haven’t heard from him since, all these years, nor have I have heard of him, until last night.

But this is all out of order. You don’t know anything about your uncle. I’ve been careful not to mention his name lest I arouse that curiosity of yours. Indeed, maybe I shouldn’t be doing so now. That’s assuming, of course, that you’ll take any of the story I’m going to relate seriously, that you won’t think I’ve confused my Henry James with M.R. James, or, worse, think it a sign of mental or emotional decay, the first hint of senility or depression. The more I insist on the truth of what I tell, the more shrill and empty my voice will sound; I know the scenario well. I risk, then, a story that might be taken as little more than a prolonged symptom of mental impairment or illness; though really, how interesting is that? In any event, it’s not as if I have to worry about you putting me in a home. Yes, I know you had no choice. Let’s start with the background, the condensed information the author delivers, after an interesting opening, in one or two well-written chapters.

George was ten years older than I, the child of what in those days was considered our parents’ middle age, as I was the child of their old age. This is to say that Mother was thirty-five when George was born, and forty-five when I was. Father was close to fifty at my birth, about the same age I was when you were born. Funny—as a boy and a young man, I used to swear that, if I was to have children, I would not wait until I was old enough to be their grandfather, and despite those vows that was exactly what I did. Do you suppose that’s why you haven’t married yet? We like to think we’re masters of our own fates, but the fact is, our parents’ examples exert far more influence on us than we realize or are prepared to realize. I like to think I was a much more youthful father to you than my father was to me, but in all fairness, fifty was a different age for me than it was for him. For me, fifty was the age of my maturity, a time of ripeness, a balance point between youth and old age; for Father, fifty was a room with an unsettlingly clear view of the grave. He died when I was fifteen, you know, while here I am, thanks to a daily assortment of colored pills closer to eighty than anyone in my family before me, with the exception, of course, of my brother.

I have few childhood memories of George: an unusually intelligent student, he left the house and the country for Oxford at the age of fifteen. Particularly gifted in foreign languages, he achieved minor fame for his translation and commentary on Les mysteres du ver, a fifteenth century French translation of a much older Latin work. England suited him well; he returned to see us in Poughkeepsie infrequently. He did, however, visit our parents’ brothers and sisters, our uncles and aunts, in and around Edinburgh on holidays, which appeared to mollify Father and Mother. (Their trips back to Scotland were fewer than George’s trips back to them.) My brother also voyaged to the Continent: France, first, which irritated Father (he was possessed by an almost pathological hatred of all things French, whose cause I never could discover, since our name is French; you can be sure, he would not have read my book on Flaubert); then Italy, which worried Mother (she was afraid the Catholics would have him); then beyond, on to those countries that for the greater part of my life were known as Yugoslavia: Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, and past them to the nations bordering the Black Sea. He made this trip and others like it, to Finland, to Turkey, to Persia as it was then called, often enough. I have no idea how he afforded any of it. Our parents sent him little enough money, and his scholarship was no source of wealth. I have no idea, either, of the purpose of these trips; when I asked him, George answered, “Research,” and said no more. He wrote once a month, never more and occasionally less, short letters in which a single nugget of information was buried beneath layers of formality and pleasantry; not like those letters I wrote to you while you were at Harvard. It was in such a letter that he told us he was engaged to be married.

Aside from the fact that it lasted barely two years, the most remarkable thing about your uncle’s marriage was your cousin, Peter, who was born seven months after it. Mother’s face wore a suspicious frown for several days after the news of his birth reached us (I think it came by telegram; your grandparents were very late installing a phone); Father was too excited by the birth of his first grandson to care. I didn’t feel much except a kind of disinterested curiosity. I was an uncle, but I was thirteen, so the role didn’t have the significance for me it might have had I been only a few years older. The chances of my seeing my nephew any time in the near future were sufficiently slim to justify my reserve; as it happened, however, my brother and his wife, whose name was Clarissa, visited us the following summer with Peter. Clarissa was quite wealthy; she was also, I believe, quite a bit older than George, though by how much I couldn’t say. Even now, after a lifetime’s practice, I’m not much good at deciphering people’s ages, which causes me no end of trouble, I can assure you. Their visit went smoothly enough, though your grandparents showed, I noticed, the razor edge of uneasiness with their new daughter-in-law’s crisp accent and equally crisp manners. Your grandmother used her wedding china every night, while your grandfather, whose speech usually was peppered with Scots words and expressions, spoke what my mother used to call “the King’s English.” Their working class origins, I suspect, rising up to haunt them.

Peter was fat and blond, a pleasant child who appeared to enjoy his place on your grandmother’s hip, which from the moment he arrived was where he spent most of his days. Any reservations Mother might have had concerning the circumstances of his birth were wiped away at the sight of him. When he returned from work, Father had a privileged place for his grandson on his knee: holding each of the baby’s hands in his hands, Father sat Peter upright on his knee, then jiggled his leg up and down, bouncing Peter as if he were riding a horse, all the while singing a string of nonsense syllables: “a leedle lidel leedle lidel leedle lidel lum.” It was something Father did with any baby who entered the house; he must have done it with me, and with George. I tried it with you, but you were less than amused by it. After what appeared to be some initial doubt at his grandfather’s behavior, when he rode up and down with an almost tragic expression on his face, Peter quickly came to enjoy and even anticipate it, and when he saw his grandfather walk in the door, the baby’s face would break into an enormous grin, and he waved his arms furiously. Clarissa was good with her son, handling him with more confidence than you might expect from a new mother; George largely ignored Peter, passing him to Clarissa, Mother, Father, or me whenever he could manage it. Much of his days George spent sequestered in his room, working, he said, on a new translation. Of what he did not specify, only that the book was very old, much older than Les mysteres du ver. He kept the door to the room locked, which I discovered, of course, trying to open it.

The three of them stayed a month, leaving with promises to write on both sides, and although it was more than a year later, it seemed the next thing anyone heard or knew Clarissa had filed for divorce. Your grandparents were stunned. They refused to tell me the grounds for Clarissa’s action, but when I lay awake at night I heard them discussing it downstairs in the living room, their voices faint and indistinguishable except when one or the other of them became agitated and shouted, “It isn’t true, for God’s sake, it can’t be true! We didn’t raise him like that!” Clarissa sued for custody of Peter, and somewhat to our parents’ surprise, I think, George counter-sued. It was not only that he did not appear possessed of sufficient funds; he did not appear possessed of sufficient interest. The litigation was interminable and bitter. Your grandfather died before it was through, struck dead in the street as we were walking back from Sunday services by a stroke whose cause, I was and am sure, was his elder son’s divorce. George did not return for the funeral; he phoned to say it was absolutely impossible for him to attend—the case and all—he was sure Father would have understood. The divorce and custody battle were not settled for another year after that. When they were, George was triumphant.

I don’t know if you remember the opening lines of What Maisie Knew. The book begins with a particularly messy divorce and custody fight, in which the father, though “bespattered from head to foot,” initially succeeds. The reason, James tells us, is “not so much that the mother’s character had been more absolutely damaged as that the brilliancy of a lady’s complexion (and this lady’s, in court, was immensely remarked) might be more regarded as showing the spots.” I can recall reading those lines for the first time: I was a senior in high school, and a jolt of recognition shot up my spine as I recognized George and Clarissa, whose final blows against one another had been struck the previous fall. I think that’s when I first had an inclination I might study old James. Unlike James’s novel, in which the custody of Maisie is eventually divided between her parents, George won full possession of Peter, which he refused to share in the slightest way with Clarissa. I imagine she must have been devastated. George packed his and Peter’s bags and moved north, to Edinburgh, where he purchased a large house on the High Street and engaged the services of a manservant, Mr. Gaunt.

Oh yes, Mr. Gaunt was an actual person. Are you surprised to hear that? I suppose he did seem rather a fantastic creation, didn’t he? I can’t think of him with anything less than complete revulsion, revulsion and fear, more fear than I wish I felt. I met him when I was in Edinburgh doing research on Stevenson and called on my brother, who had returned from the Shetlands that morning and was preparing to leave for Belgium later that same night. The butler was exactly as I described him to you in the story, only more so.

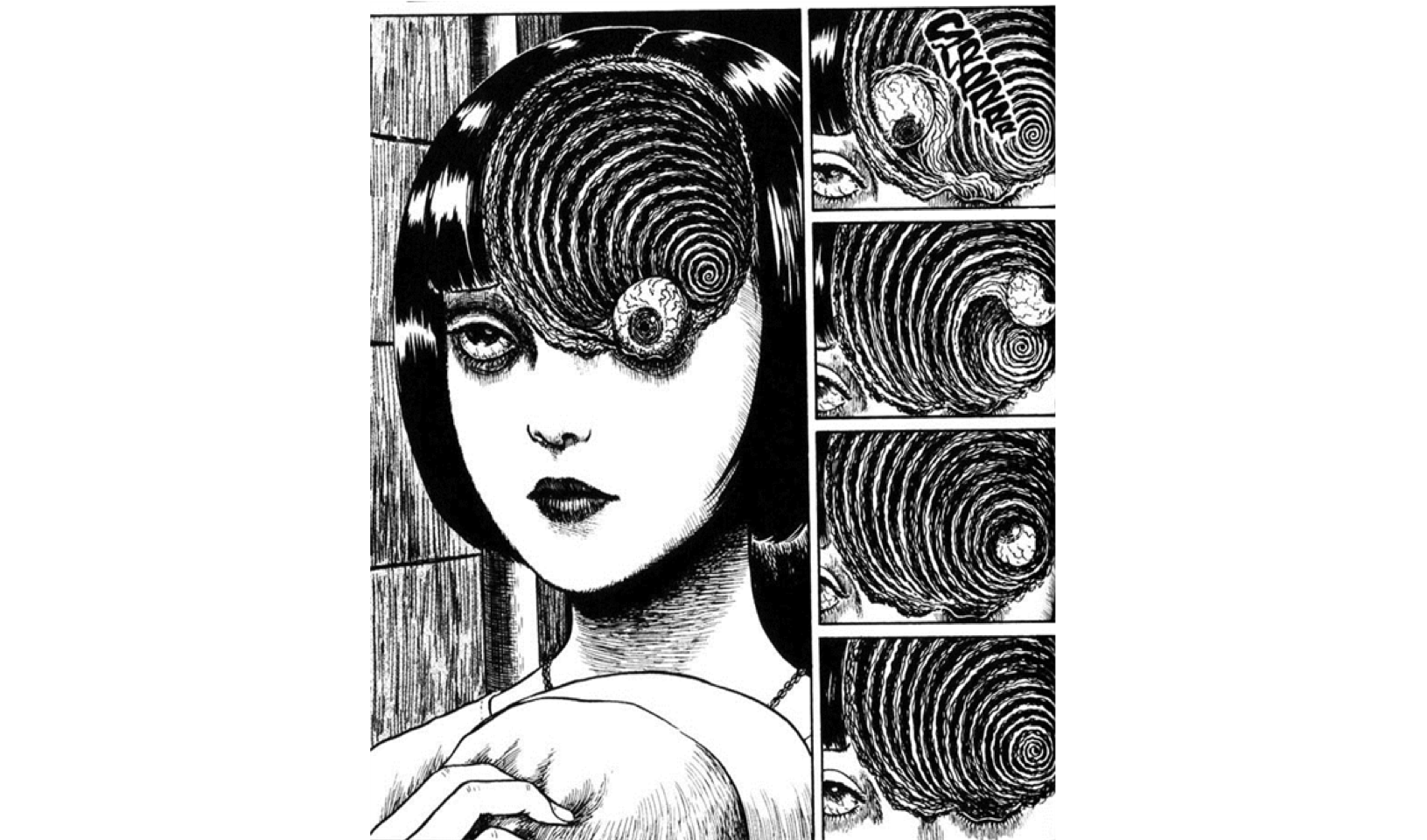

Mr. Gaunt never said a word. He was very tall, and very thin, and his skin was very white and very tight, as if he were wearing a suit that was too small. He had a long face and long, lank, thin, colorless hair, and a big, thick jaw, and tiny eyes that peered out at you from the deep caverns under his brows. He did not smile, but kept his mouth in a perpetual pucker. He wore a black coat with tails, a gray vest and gray pants, and a white shirt with a gray cravat. He was most quiet, and if you were standing in the kitchen or the living room and did not hear anything behind you, you could expect to turn around and find Mr. Gaunt standing there.

Mr. Gaunt served the meals, though he himself never ate that the boy saw, and escorted visitors to and from the boy’s father when the boy’s father was home, and, on nights when he was not home, Mr. Gaunt unlocked the door of the forbidden study at precisely nine o’clock and went into it, closing the door behind him. He remained there for an hour. The boy did not know what the butler did in that room, nor was he all that interested in finding out, but he was desperate for a look at his father’s study.

Your uncle claimed to have contracted Gaunt’s service during one of his many trips, and explained that the reason Gaunt never spoke was a thick accent—I believe George said it was Belgian—that marred his speech and caused him excruciating embarrassment. As Gaunt served us tea and shortbread, I remember thinking that something about him suggested greed, deep and profound: his hands, whose movements were precise yet eager; his eyes, which remained fixed on the food, and us; his back, which was slightly bent, inclining him towards us but having the opposite effect, making him seem as if he were straining upright, resisting a powerful downward pull. No doubt it was the combination of these things. Whatever the source, I was noticeably glad to see him exit the room; although, after he had left, I had the distinct impression he was listening at the door, hunched down, still greedy.

As you must have guessed, the boy in our fairy tale was Peter, your cousin. He was fourteen when he had his run in with Mr. Gaunt, older, perhaps, than you had imagined him; the children in fairy tales are always young children, aren’t they? I should also say more about the large house in which he lived. It was a seventeenth century mansion located on the High Street in Edinburgh, across the street and a few doors down from St. Giles’s Cathedral. Its inhabitants had included John Jackson, a rather notorious character from the early nineteenth century. There’s a mention of him in James’s notebooks: he heard Jackson’s story while out to dinner in Poughkeepsie, believe it or not, and considered treating it in a story before rejecting it as, “too lurid, too absolutely over the top.” The popular legend, of whose origins I’m unsure, is that Jackson, a defrocked Anglican priest, had truck with infernal powers. Robed and hooded men were seen exiting his house who had not been seen entering it. Lights glowed in windows, strange cries and laughter sounded, late at night. A woman who claimed to have worked as Jackson’s chambermaid swore there was a door to Hell in a room deep under the basement. He was suspected in the vanishings of several local children, but nothing was proved against him. He died mysteriously, found, as I recall, at the foot of a flight of stairs, apparently having tumbled down them. His ghost, its neck still broken, was sighted walking in front of the house, looking over at St. Giles and grinning; about what, I’ve never heard.

Most of this information about the house I had from George during my visit; it was one of the few subjects about which I ever saw him enthused. I don’t know how much if any of it your cousin knew; though I suspect his father would have told him all. Despite the picture its history conjures, the house was actually quite pleasant: five stories high including the attic, full of surprisingly large and well-lit rooms, decorated with a taste I wouldn’t have believed George possessed. There was indeed a locked study: it composed the entirety of the attic. I saw the great dark oaken door to it when your uncle took me on a tour of the house: we walked up the flight of stairs to the attic landing and there was the entrance to the study. George did not open it. I asked him if this was where he kept the bodies, and although he cheerfully replied that no, no, that was what the cellar was for, his eyes registered a momentary flash of something that was panic or annoyance. I did not ask him to open the door, in which there was a keyhole of sufficient diameter to afford a good look into the room beyond. Had my visit been longer, had I been his guest overnight, I might have stolen back up to that landing to peak at whatever it was my brother did not wish me to see. Curiosity, it would appear, does not just run in our family: it gallops.

Peter lived in this place, his father’s locked secret above him, his only visitors his tutors, his only companion the silent butler. That’s a bit much, isn’t it? During our final conversation, George told me that Peter had been a friendless boy, but I doubt he knew his son well enough to render such a verdict with either accuracy or authority. Peter didn’t know many, if any, other children, but I like to think of your cousin having friends in the various little shops that line the High Street. You know where I’m talking about, the cobbled street that runs in a straight line up to the Castle. You remember those little shops with their flimsy t-shirts, their campy postcards, their overpriced souvenirs. We bought the replica of the Castle that used to sit on the mantelpiece at one of them, along with a rather expensive pin for that girl you were involved with at the time. (What was her name? Jane?) I like to think of Peter, out for a walk, stopping in several shops along the way, chatting with the old men and women behind the counter when business was slow. He was a fine conversationalist for his age, your cousin.

I had met him again, you see, when he was thirteen, the year before the events I’m relating occurred. George was going to be away for the entire summer, so Peter came on his own to stay with your grandmother. I was living in Manhattan—actually, I was living in a cheap apartment across the river in New Jersey and taking the ferry to Manhattan each morning. My days I split teaching and writing my dissertation, which was on the then-relatively-fresh topic of James’s later novels, particularly The Golden Bowl, and their modes of narration. Every other week, more often when I could manage it, I took the train up to your grandmother’s to spend the day and have dinner with her. This was not as great a kindness as I would like it to seem: my social life was nonexistent, and I was desperately lonely. Thus, I visited Peter several times throughout June, July, and August.

At our first meeting he was unsure what to make of me, spending most of the meal silently staring down at his plate, and asking to be excused as soon as he had finished his dessert. Over subsequent visits, however, our relationship progressed. By our last dinner he was speaking with me freely, shaking my hand vigorously when it was time for me to leave for my bus and telling me that he had greatly enjoyed making my acquaintance. What did he look like? Funny: I don’t think I have a picture of him; not from that visit, anyway. He wasn’t especially tall; if he was due an adolescent growth-spurt, it had yet to arrive. His hair, while not the same gold color it had been when he was a baby, still was blond, slightly curled, and his eyes were dark brown. His face, well, as is true with all children, his face blended both his parents’, although in his case the blend was particularly fine. What I mean is, unlike you, whose eyes and forehead have always been identifiably mine and whose nose and chin have always been identifiably your mother’s, Peter’s face, depending on the angle and lighting, appeared to be either all his father or all his mother. Even looking at him directly, you could see both faces simultaneously. He spoke with an Edinburgh accent, crisp and clear, and when he was excited or enthusiastic about a subject, his words would stretch out: “That’s maaaarvelous.” He told your grandmother her accent hadn’t slipped in the least, and she smiled for the rest of the day.

He was extremely bright, and extremely interested in ancient Egypt, about which his father had provided him with several surprisingly good books. He could not decide whether to be a philologist, like his father, or an Egyptologist, which sounded more interesting; he inclined to Egyptology, but thought his father would appreciate him following his path. Surprising and heartbreaking—horrifying—as it seems in retrospect, Peter loved and missed his father. He was very proud of George: he knew of and appreciated George’s translations, and confided in us his hope that one day he might achieve something comparable. “My father’s a genius,” I can hear him saying, almost defiantly. We were sitting at your grandmother’s dining room table. I can’t remember how we had arrived at the subject of George, but he went on, “Aye, a genius. None of his teachers were ever as smart as him. None of them could make head nor tail of Les mysteres du ver, and my father translated the whole thing, on his own. There was this one teacher who thought he was something, and he was pretty smart, but my father was smarter; he showed him.”

“Of course he’s smart, dear,” your grandmother said. “He’s a Farange. Just like you and your uncle.”

“And your Granny,” I said.

“Oh, go on, you,” she said.

“He’s translated things that no one’s even heard of,” Peter went on. “He’s translated pre-dynastic Egyptian writing. That’s from before the pyramids, even. That’s fifty-five centuries ago. Most folk don’t even know it exists.”

“Has he let you see any of it?” I asked.

“No,” Peter said glumly. “He says I’m not ready yet. I have to master Latin and Greek before I can move on to just hieroglyphics.”

“I’m sure you will,” your grandmother said, and we moved on to some other topic. Later, after Peter was asleep, she said to me, “He’s a lovely boy, our Peter, a lovely boy. So polite and well-mannered. But he seems awfully lonely to me. Always with his nose in a book: I don’t think his father spends nearly enough time with him.”

Peter did not speak of his mother.

He knew ancient Egypt as if he had lived in it: your grandmother and I spent more than one dinner listening to your cousin narrate such events as the building of the Great Pyramid of Giza, the factual accuracy of which I couldn’t verify but whose telling kept me enthralled. Peter was a born raconteur: as he narrated his history, he would assume the voices of the different figures in it, from Pharaoh to slave. “The Great Pyramid,” he would say, addressing the two of us as if we were a crowd at a lecture hall, “was built for the Pharaoh Khufu. The Greeks called him Cheops. He lived during the Fourth Dynasty, which was about four and half thousand years ago. The moment he became Pharaoh, Khufu started planning his pyramid, because, really, it was the most important thing he was ever going to build. The Egyptians were terribly concerned with death, and spent much of their lives preparing for it. He picked a site on the western bank of the Nile. The Egyptians thought the western bank was a special place because the sun set in the west. The west was the place of the dead, if you like, the right place to build your tomb. That’s all it was, after all, a pyramid. Not that you’d know that from the name: it’s a Greek word, ‘pyramid;’ it comes from ‘wheat cake.’ The Greeks thought the pyramids looked like giant pointy wheat cakes. We get a lot of names for Egyptian things from the Greeks: like ‘pharaoh,’ which they adapted from an Egyptian word that meant ‘great house.’ And ‘sarcophagus,’ that comes from the Greek for ‘flesh-eating.’ Why they called funeral vaults flesh-eaters I’ll never know.” And so on. He did love a good digression, your cousin: he would have made a fine college professor.

So you see, all this is why I dispute your uncle’s claim that he was friendless, solitary: given the right set of circumstances, Peter could be positively garrulous. I have little trouble picturing him keeping the proprietor of a small bookshop, say, entertained with the story of the Pharaoh—I can’t remember his name—who angered his people so that after his death his statues and monuments were destroyed and he was not buried in his own tomb; no one knew what had become of his body. No one knew what happened to his son either. I planned to take Peter to the Met, to see their Egyptian collection, but for reasons I can’t recall we never went. At our final visit, he suggested we write. Initially, I demurred: I was buried in the last chapter of my dissertation, which I had expected to be forty pages I could write in a month but which rapidly had swelled to eighty-five pages that would consume my every waking moment for the next four months. We could write when I was finished, I explained. Peter pleaded with me, though, and in the end I agreed. We didn’t write much, just four letters from him and three replies from me.

I found myself leafing through Peter’s letters the winter after his visit, when your uncle telephoned your grandmother to inform her that your cousin was missing: he had run away from home and no one knew where he was. Your grandmother was distraught; I was, too, when she called me with the news of Peter’s vanishing. She was upset at George, who apparently had shown only the faintest trace of emotion while delivering to her what she rightly regarded as terrible information. He was sure Peter would turn up, George said, boys will be boys and all that, what can you do? Lack of proper family feeling in anyone bothered your grandmother; it was her pet peeve; and she found it a particularly egregious fault in one of her own, raised to know better. “It’s a good thing your father isn’t alive to see this,” she said to me, and I was unsure whether she referred to Peter’s running away or George’s understated reaction to it.

At the time, I suspected Peter might be making his way to his mother’s, and went so far as to contact Clarissa myself, but if such was her son’s plan she knew nothing about it. Through her manners I could hear the distress straining her voice, and another thing, a reserve I initially could not understand. Granted that speaking to your former brother-in-law is bound to be awkward, Clarissa’s reticence was still in excess of any such awkwardness. Gradually, as we stumbled our way through a conversation composed of half-starts and long pauses, I understood that she was possessed by a mixture of fear and loathing: fear, because she suspected me of acting in concert with my brother to trick and trap her (though what more she had left to lose at that point I didn’t and don’t know; her pride, I suppose); loathing, because she thought that I was cut from the same cloth as George. Whatever George had done to prompt her to seek divorce a dozen years before, her memory and repugnance of it remained sufficiently fresh to make talking to me a considerable effort.

Peter didn’t appear at his mother’s, or any other relative’s, nor did he return to his father’s house. Against George’s wishes, I’m sure, Clarissa involved the police almost immediately. Because of her social standing and the social standing of her family, I’m equally sure, they brought all their resources to bear on Peter’s disappearance. The case achieved a notoriety that briefly extended across the Atlantic, scandalizing your grandmother; though I’m not aware that anyone ever connected George to us. Suspecting the worst, the police focused their attentions on George, bringing him in for repeated and intense questioning, investigating his trips abroad, ransacking his house. Strangely, in the midst of all this, Gaunt apparently went unnoticed. After subjecting George to close scrutiny for several weeks—which yielded no clue to where Peter might be or what might have happened to him—the detective in charge of the investigation fell dead of a heart attack while talking to your uncle on the telephone. As the man was no more than thirty, this was a surprise. His replacement was more kindly disposed to George, judging that he had underwent enough and concentrating the police’s attentions elsewhere. Your cousin was not found; he was never found. Though your grandmother continued to hold out hope that he was alive until literally the day she died, thinking he might have found his way to Egypt, I didn’t share her optimism, and reluctantly concluded that Peter had met his end.

I was correct, though I had no way of knowing how horrible that end had been. What happened to Peter took place while his father was out of the house; in Finland, he said. It was late winter; when Scotland has yet to free itself from its long nights and the sky is dark for much of the day. Peter had been living with his father’s locked study for eleven years. So far as I know, he had shown no interest in the room in the past, which strikes me as a bit unusual, although I judge all other children’s curiosity against yours, an unfair comparison. Perhaps George had told his own cautionary tale. There was no reason to expect Peter’s interest to awaken at that moment, but it did. He became increasingly intrigued by that heavy door and what it concealed. I know this, you see, because it was in the first letter he sent to me, which arrived less than a month after his return home. He decided to confide in me, and I was flattered. Though he didn’t write this to me, I believe he must have associated his father’s study with those Egyptian tombs he’d been reading about; he must have convinced himself of a parallel between him entering that room and Howard Carter entering Tutankhamun’s tomb. His father provided him a generous allowance, so I know he wasn’t interested in money, as he himself was quick to reassure me in that same letter. He didn’t want me to suspect his motives: he was after knowledge; he wanted to see what was hidden behind the dark door. Exactly how long that desire burned in him I can’t say; he admitted that while he’d been wandering the woods behind your grandmother’s house, he’d been envisioning himself walking through that room in his father’s house, imagining its contents. He didn’t specify what he thought those contents might be, and I wonder how accurate his imagination was. Did he picture the squat bookcases overstuffed with books, scrolls, and even stone tablets; the long tables heaped with goblets, boxes, candles, jars; the walls hung with paintings and drawings; the floor chalked with elaborate symbols? (I describe it well, don’t I? I’ve seen it—but that must wait.)

It was with his second letter that Peter first disclosed his plans to satisfy his curiosity; plans I encouraged, if only mildly, when at last I sent him a reply. He would have to be careful, I wrote, if he were caught, I had no doubt the consequences would be severe. I didn’t believe they actually would be, but I enjoyed participating in what I knew was, for your cousin, a great adventure. I suggested that he take things in stages, that he try a brief trip up to the attic stairs first and see how that went. What length of time was required for him to amass sufficient daring to venture the narrow flight of stairs to the attic landing I can’t say. Perhaps he climbed a few of the warped, creaking stairs one day, before his nerve broke and he bolted down them back to his room; then a few more the next day; another the day after that; and so on, adding a stair or two a day until at last he stood at the landing. Or perhaps he rushed up the staircase all at once, his heart pounding, his stomach weak, taking the stairs two and three at a time, at the great dark door almost before he knew it. Having reached the landing, was he satisfied with his accomplishment? or were his eyes drawn to the door, to the wide keyhole that offered a view of the room beyond? We hadn’t discussed that: did it seem too much, a kind of quantum leap from what he had risked scaling the stairs? or did it seem the next logical step: in for a penny, in for a pound, as it were? Once he stood outside the door, he couldn’t have waited very long to lower his eye to the keyhole. When he did, his mouth dry, his hands shaking slightly, expecting to hear either his father of Mr. Gaunt behind him at every moment, he was disappointed: the windows in the room were heavily curtained, the lights extinguished, leaving it dim to the point of darkness on even the brightest day, the objects inside no more than confused shadows.

Peter boiled down all of this to two lines in his third letter, which I received inside a Christmas card. “I finally went to the door,” he wrote, “and even looked in the keyhole! But everything was dark, and I couldn’t see at all.” Well, I suggested in my response, he would need to spy through the door when the study was occupied. Why not focus on Mr. Gaunt and his nine o’clock visitations? His father’s returns home were too infrequent and erratic to be depended upon, and I judged the consequences of discovery by his father to be far in excess of those of discovery by the butler. (If I’d known….) Peter felt none of my unease around Mr. Gaunt, which was understandable, given that the butler had been a fixture in his home and life for more than a decade. In his fourth and final letter, Peter thanked me for my suggestion. He had been pondering a means to pilfer Gaunt’s key to the room, only to decide that, for the moment, such an enterprise involved a degree of risk whatever was in the room might not be worth. I had the right idea: best to survey the attic clearly, then plan his next step. He would wait until his father was going to be away for a good couple of week, which wouldn’t be until February. In the meantime, he was trying to decipher the sounds of Mr. Gaunt’s nightly hour in the study: the two heavy clumps, the faint slithering, the staccato clicks like someone walking across the floor wearing tap shoes. I replied that it could be the butler was practicing his dancing, which I thought was much funnier at the time than I realize now it was, but that it seemed more likely what Peter was hearing was some sort of cleaning procedure. He should be careful, I wrote, obviously, the butler knew Peter wasn’t supposed to be at the study, and if he caught him there, he might very well become quite upset, as George could hold him responsible for Peter’s trespass.

I didn’t hear from Peter again. For a time, I assumed this was because his enterprise had been discovered and him punished by his father. Then I thought it must be because he was burdened with too much schoolwork: the tutors his father had brought to the house for him, he had revealed in his second letter, were most demanding. I intended to write to him, to inquire after the status of our plan, but whenever I remembered my intention I was in the middle of something else that absolutely had to be finished and couldn’t be interrupted, or so it seemed, and I never managed even to begin a letter. Then George called your grandmother, to tell her Peter was gone.

It was more than a quarter-century until I learned Peter’s fate. Sitting there on the back porch of the house in Highland, I heard it all from my older brother who, in turn, had had it from Gaunt. Oh yes, from Mr. Gaunt: our story, you see, was never that far from the truth. Indeed, it was closer, much closer, than I wish it were.

George left Scotland for an extended trip to Finland the first week in February. He would be away, he told Peter, for at least two weeks, and possibly a third if the manuscripts he was going to view were as extensive as he hoped. Peter wore an appropriately glum face at his father’s departure, which pleased George, who had no idea of his son’s secret ambition. For the first week after his father left, Peter maintained his daily routine. When at last the appointed date for his adventure arrived, though, he spent it in a state of almost unbearable anticipation, barely able to maintain conversation with any of his shopkeeper friends, inattentive to his tutors, uninterested in his meals. This last would not have escaped Mr. Gaunt’s notice.

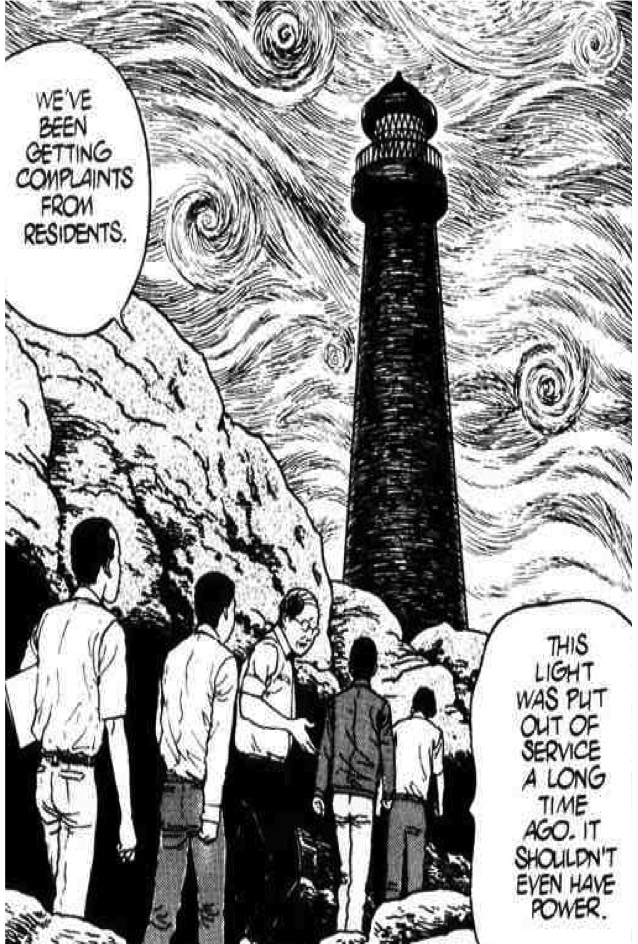

After spending the late afternoon and early evening roaming through the first three floors of the house, leafing through the library, practicing his shots at the pool table, spinning the antique globe in the living room, Peter declared he was going to make an early night of it, which also would have caught the butler’s attention. From first-hand experience, I can tell you that Peter was something of a night owl, retiring to bed only when your grandmother insisted and called him by his full name, and even then reading under the sheets with a flashlight. Gaunt may have suspected your cousin’s intentions; I daresay he must have. This would explain why, an hour and a half after Peter said he was turning in, when his bedroom door softly creaked open and Peter, still fully dressed, crept out and slowly climbed the narrow staircase to the attic landing, he found the door to the study standing wide open. It could also be that the butler had grown careless, but that strikes me as unlikely. Whatever Mr. Gaunt was, he was most attentive.

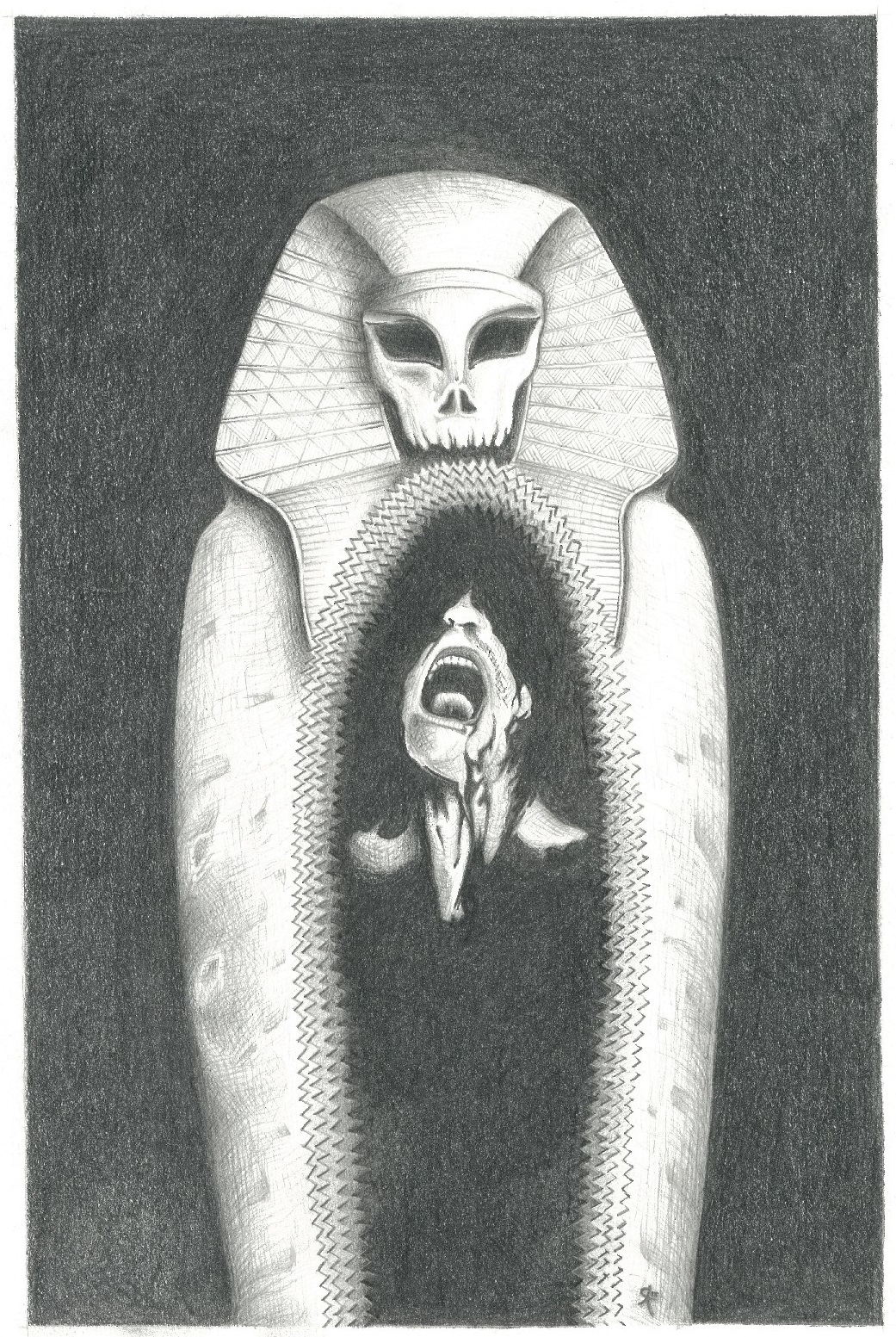

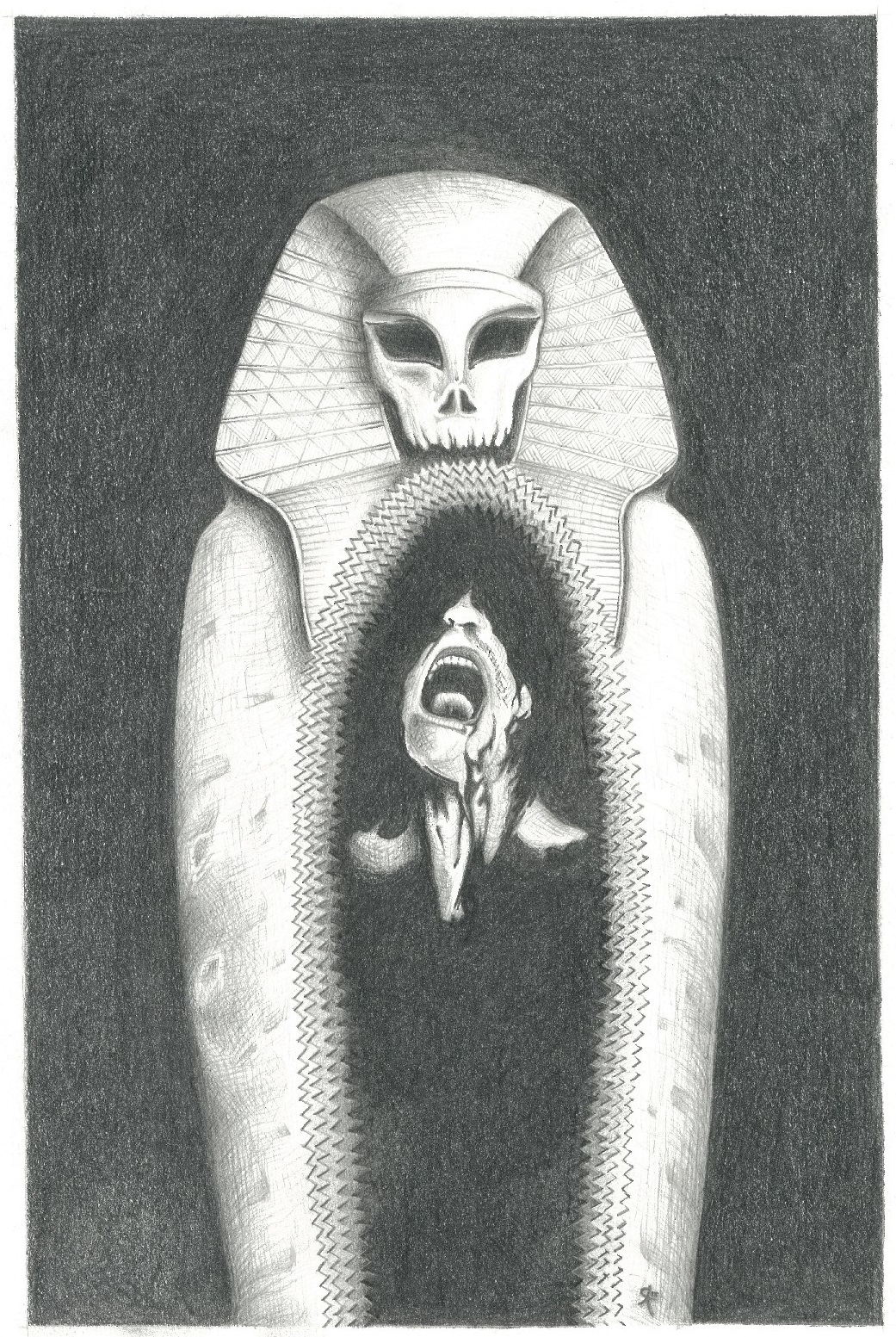

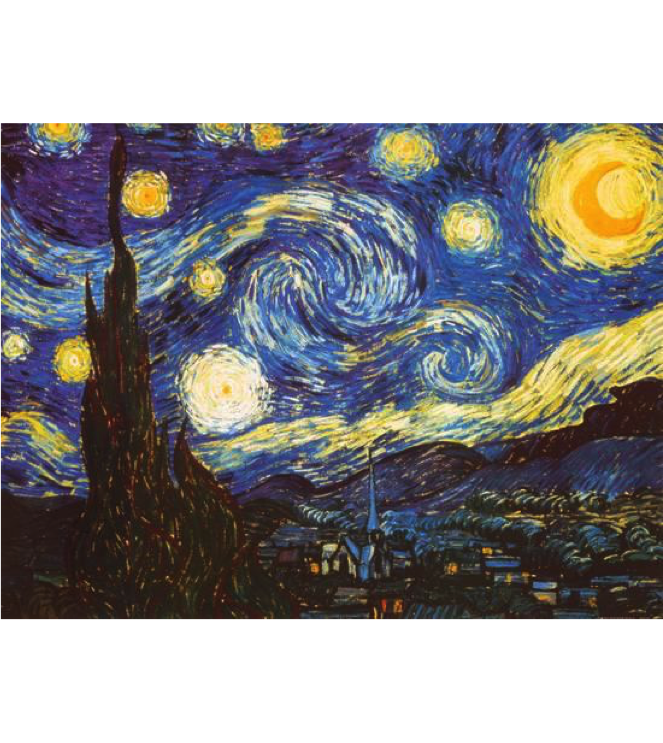

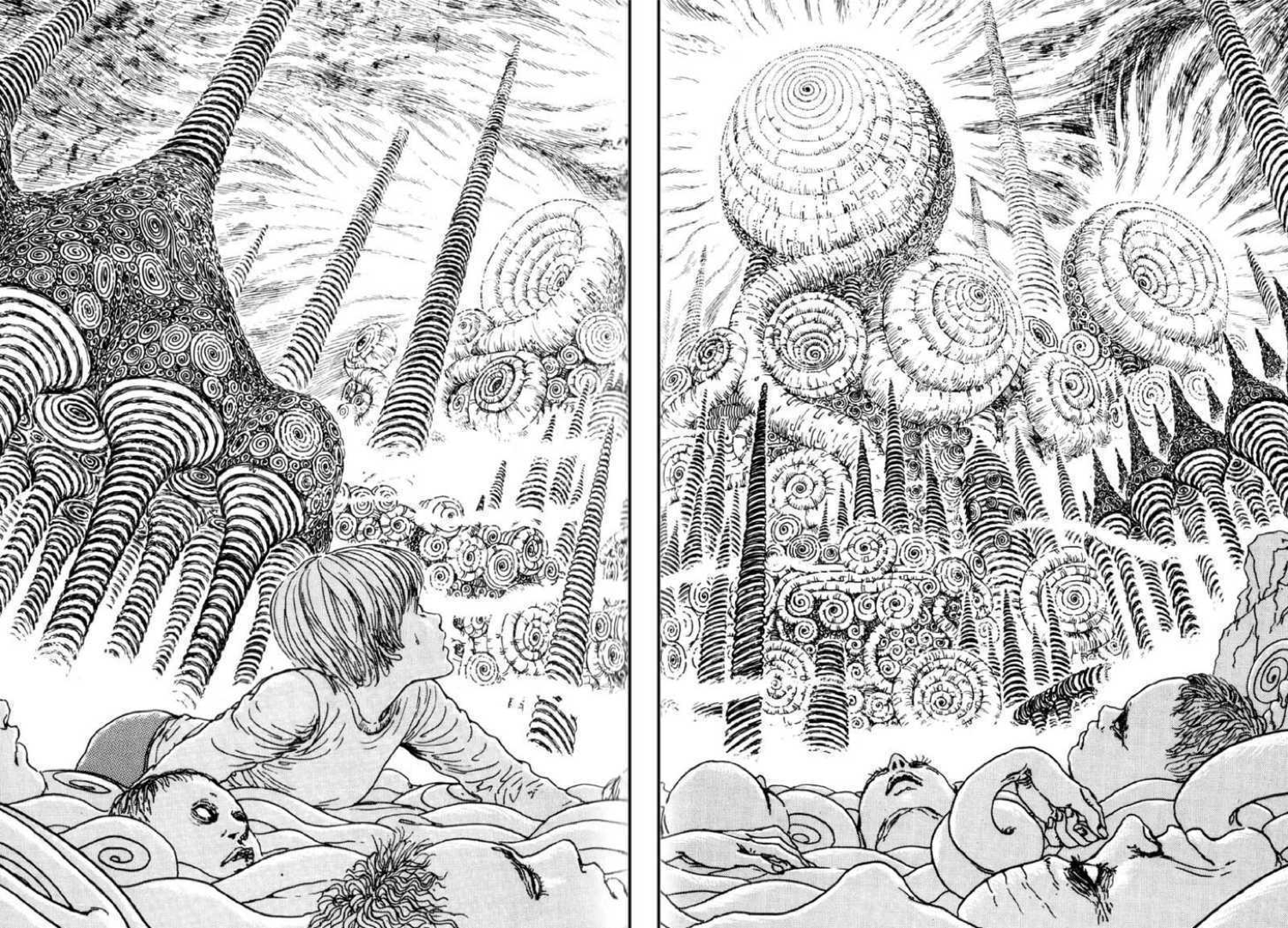

Your cousin stood there at the top of the stairs, gazing at the room that stretched out like a hall and was lit by globed lights dangling from the slanting ceiling. He saw the overstuffed bookcases. He saw the tables heaped high with assorted objects. He saw the paintings crowding the walls, the chalked symbols swarming over the floor. If there was sufficient time for him to study anything in detail, he may have noticed the small Bosch painting, The Alchemical Wedding, hanging across from him. It was—and still is—thought lost. It’s the typical Bosch scene, crowded with all manner of people and creatures real and fantastic, most of them merrily dancing around the central figures, a man in red robes and a skeleton holding a rose being married by a figure combining features of a man and an eagle. The nearest table displayed a row of jars, each of them filled with pale, cloudy fluid in which floated a single, pink, misshapen fetus; approaching to examine them, he would have been startled to see the eyes of all the tiny forms open and stare at him. If any object caught his attention, it would have been the great stone sarcophagus leaning against the wall to his left, its carved face not the placid mask familiar to him from photos and drawings, but vivid and angry, its eyes glaring, its nostrils flaring, its mouth open wide and ringed with teeth. That would have chased any fear of discovery from his mind and brought him boldly into the study.

It could be, of course, that Peter’s gaze, like the boy in our story’s, was immediately captured by what was hanging on the antique coat-stand across from him.

At first, the boy thought it was a coat, for that is, after all, what you expect to find on a coat-stand. He assumed it must be Mr. Gaunt’s coat, which the butler must have taken off and hung up when he entered the study. Why the butler should have been wearing a coat as long as this one, and with a hood and gloves attached, inside the house, the boy could not say. The more the boy studied it, however, the more he thought that it was a very strange coat indeed: for one thing, it was not so much that the coat was long as that there appeared to be a pair of pants attached to it, and, for another, its hood and gloves were unlike any he had seen before. Where the coat was black, the hood was a pale color that seemed familiar but that the boy could not immediately place. What was more, the hood seemed to be hairy, at least the back of it did, while the front contained a number of holes whose purpose the boy could not fathom. The gloves were of the same familiar color as the hood.

The boy stood gazing at the strange coat until he heard a noise coming from the other end of the study. He looked toward it, but saw nothing: just a tall skeleton dangling in front of another bookcase. He looked away and the noise repeated, a sound like a baby’s rattle, only louder. The boy looked again and again saw nothing, only the bookcase and, in front of it, the skeleton. It took a moment for the boy to recognize that the skeleton was not dangling, but standing. As he watched, its bare, grinning skull turned toward him, and something in the tilt of its head, the crook of its spine, sent the boy’s eyes darting back to the odd coat. Now, he saw that it was a coat, and pants, and hands, and a face: Mr. Gaunt’s hands and face. Which must mean, he realized, that the skeleton at the other end of the room, which replaced the book it had been holding on top of the bookcase and stepped in his direction, was Mr. Gaunt. The boy stared at the skeleton slowly walking across the room, still far but drawing closer, its blank eyes fixed on him, and, with a scream, ran back down the stairs. Behind him, he heard the rattle of the skeleton’s pursuit.

There in his father’s study, your cousin Peter saw a human skeleton, Mr. Gaunt’s skeleton—or the skeleton that was Gaunt—rush toward him from the other side of the room. The skeleton was tall, slightly stooped, and when it moved, its dull yellow bones clicked against each other like a chorus of baby rattles. Peter screamed, then bolted the room. He leapt down the attic stairs two and three at a time, pausing at the fourth floor landing long enough to throw closed the door to the stairs and grasp at the key that usually rested in its lock but now was gone, taken, he understood, by Mr. Gaunt. Peter ran down the long hallway to the third floor stairs and half-leapt down them. He didn’t bother with the door at the third floor landing: he could hear that chorus of rattles clattering down the stairs, too close already. He raced through the three rooms that lay between the third floor landing and the stairway to the second floor, hearing Gaunt at his back as he hurdled beds, chairs, couches; ducked drapes; rounded corners. A glance over his shoulder showed the skeleton running after him like some great awkward bird, its head bobbing, its knees raised high. He must have been terrified; there would have been no way for him not to have been terrified. Imagine your own response to such a thing. I wouldn’t have been able to run; I would have been paralyzed, as much by amazement as by fear. As it was, Gaunt almost had him when Peter tipped over a globe in his path and he fell crashing behind him. With a final burst of speed, Peter descended the last flight of stairs and made the front door, which he heaved open and dashed through into the street.

Between Peter’s house and the house to its left as you stood looking out the front door was a close, an alley. Peter rushed to and down it. It could be that panic drove him, or that he meant to evade Gaunt by taking a route he thought unknown to the butler. If the latter was the case, the sound of bones rattling across the cobblestones, a look back at the naked grin and the arm grasping at him, would have revealed his error instantly, with no way for him to double-back safely. I suspect the skeleton did something to herd Peter to that alley, out of sight of any people who might be on the street; I mean it worked a spell of some kind. The alley sloped down, gradually at first, then steeply, ending at the top of a series of flights of stone stairs descending the steep hillside to Market Street below. From Market Street, it’s not that far to the train station, which may have been Peter’s ultimate destination. His heart pounding, his breath rushing in and out, he sped down the hill, taking the stairs two, three, four at a time, his shoes snapping loudly on the stone, the skeleton close, swiping at him with a claw that tugged the collar of his sweater but failed to hold it.

Halfway down the stairs, not yet to safety but in sight of it, Peter’s left foot caught his right foot, tripping and tumbling him down the remaining stairs to the landing below, where he smashed into the bars of an iron guardrail. Suddenly, there was no air in his lungs. As he lay sprawled on his back, trying to breathe, the skeleton was on him, descending like a hawk on a mouse. He cried out, covering his eyes. Seizing him by the sweater front, Gaunt hauled Peter to his feet. For a second that seemed to take years, that fleshless smile was inches from his face, as if it were subjecting him to the most intense scrutiny. He could smell it: an odor of thick dust, with something faintly rancid beneath it, that brought the bile to his throat. He heard a sound like the whisper of sand blowing across a stone floor, and realized it was the skeleton speaking, bringing speech from across what seemed a great distance. It spoke one word, “Yes,” drawing it out into a long sigh that did not stop so much as fade away: Yyyeeeeeessssssss…. Then it jerked its head away, and began pulling him back up the stairs, to the house and, he knew, the study. When, all at once, his lungs inflated and he could breathe again, Peter tried to scream. The skeleton slapped its free hand across his mouth, digging the sharp ends of its fingers and thumb into his cheeks, and Peter desisted. They reached the top of the stairs and made their way up the close. How no one could have noticed them, I can’t say, though I suspect the skeleton had done something to insure their invisibility; yes, more magic. At the front door, Peter broke Gaunt’s grip and attempted to run, but he had not taken two steps before he was caught by the hair, yanked off his feet, and his head was slammed against the pavement. His vision swimming, the back of his head a knot of agony, Peter was led into the house. His knee cracked on an end-table; his shoulder struck a doorframe. As he was dragged to the study, did he speak to the creature whose claw clenched his arm? A strange question, perhaps, but since first I heard this story myself I have wondered it. Your cousin had a short time left to live, which he may have suspected; even if he did not, he must have known that what awaited him in the study would not be pleasant, to say the least. Did he apologize for his intrusion? Did he try to reason with his captor, promise his secrecy? Or did he threaten it, invoke his father’s wrath on his return? Was he quiet, stoic or stunned? Was his mind buzzing with plans of last minute escape, or had it accepted that such plans were beyond him?

There are moments when the sheer unreality of an event proves overwhelming, when, all at once, the mind can’t embrace the situation unfolding around it and refuses to do so, withholding its belief. Do you know what I mean? When your grandfather died, later that same afternoon I can remember feeling that his death was not yet permanent, that there was some means still available by which I could change it, and although I didn’t know what that means was, I could feel it trembling on the tip of my brain. When your mother told me that she was leaving me for husband number two, that they already had booked a flight together for the Virgin Islands, even as I thought, Well it’s about time: I wondered how long it would take this to arrive, I also was thinking, This is not happening: this is a joke: this is some kind of elaborate prank she’s worked up, most likely with someone else, someone at the school, probably one of my colleagues; let’s see, who loves practical jokes? While she explained the way my faults as a husband had led her to her decision, I was trying to analyze her sentence structure, word choice, to help me determine who in the department had helped her script her lines. A few years later, when she called to tell me about husband number three, I was much more receptive. All of which is to say that, if it was difficult for me to accommodate events that occur on a daily basis, how much more difficult would it have been for your cousin to accept being dragged to his father’s study by a living skeleton?

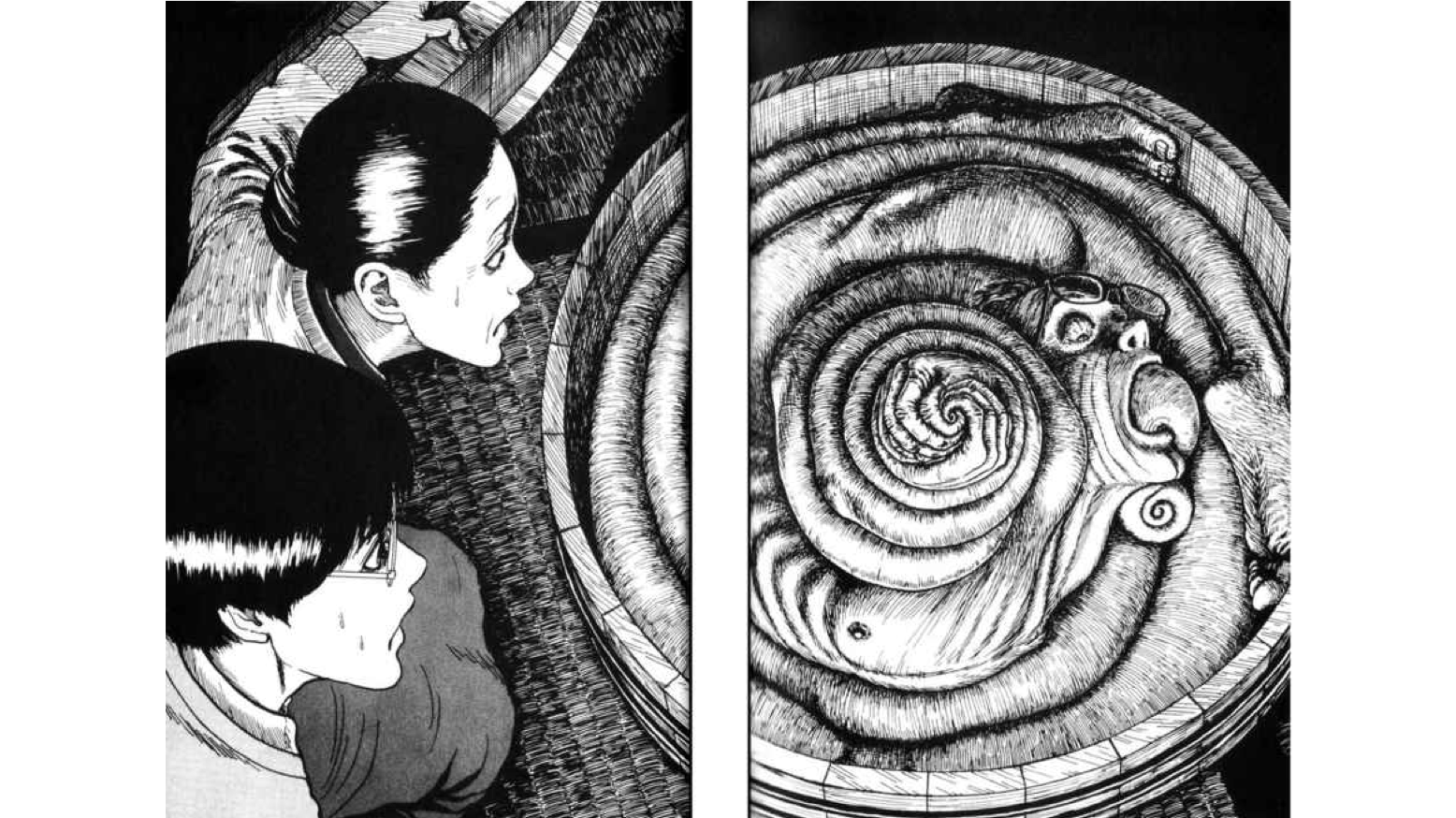

Once they were in the study, Gaunt wasted no time, making straight for the great stone sarcophagus. Peter screamed with all the force he could muster, calling for help from anyone who could hear him, then wailing in pure animal terror. The skeleton made no effort to silence him. At the sarcophagus with its furious visage, Gaunt brought his stark face down to Peter’s a second time, as if for a last look at him. He heard that faint whisper again, what sounded like the driest of chuckles. Then it reached out and slid the massive stone lid open with one spindly arm. The odor of decay, the ripe stench of a dead deer left at the side of the road for too many hot days, filled the room. Gagging, Peter saw that the interior of the sarcophagus was curiously rough, not with the roughness of, say, sandstone, but with a deliberate roughness, as if the stone had been painstakingly carved into row upon row of small sharp points, like teeth. The skeleton flung him into that smell, against those points. Before he could make a final, futile gesture of escape, the lid closed and Peter was in darkness, swathed in the thick smell of rot, his last sight the skeleton’s idiot grin. Nor was that the worst. He had been in the stone box only a few seconds, though doubtless it seemed an eternity, when the stone against which he was leaning grew warm. As it warmed, it shifted, the way the hide of an animal awakening from a deep sleep twitches. Peter jerked away from the rough stone, his heart in his throat as movement rippled through the coffin’s interior. If he could have been fortunate, his terror would have jolted him into unconsciousness, but I know this was not the case. If he was unlucky, as I know he was, he felt the sides of the sarcophagus abruptly swell toward him, felt the rows of sharp points press against him, lightly at first, then more insistently, then more insistently still, until—

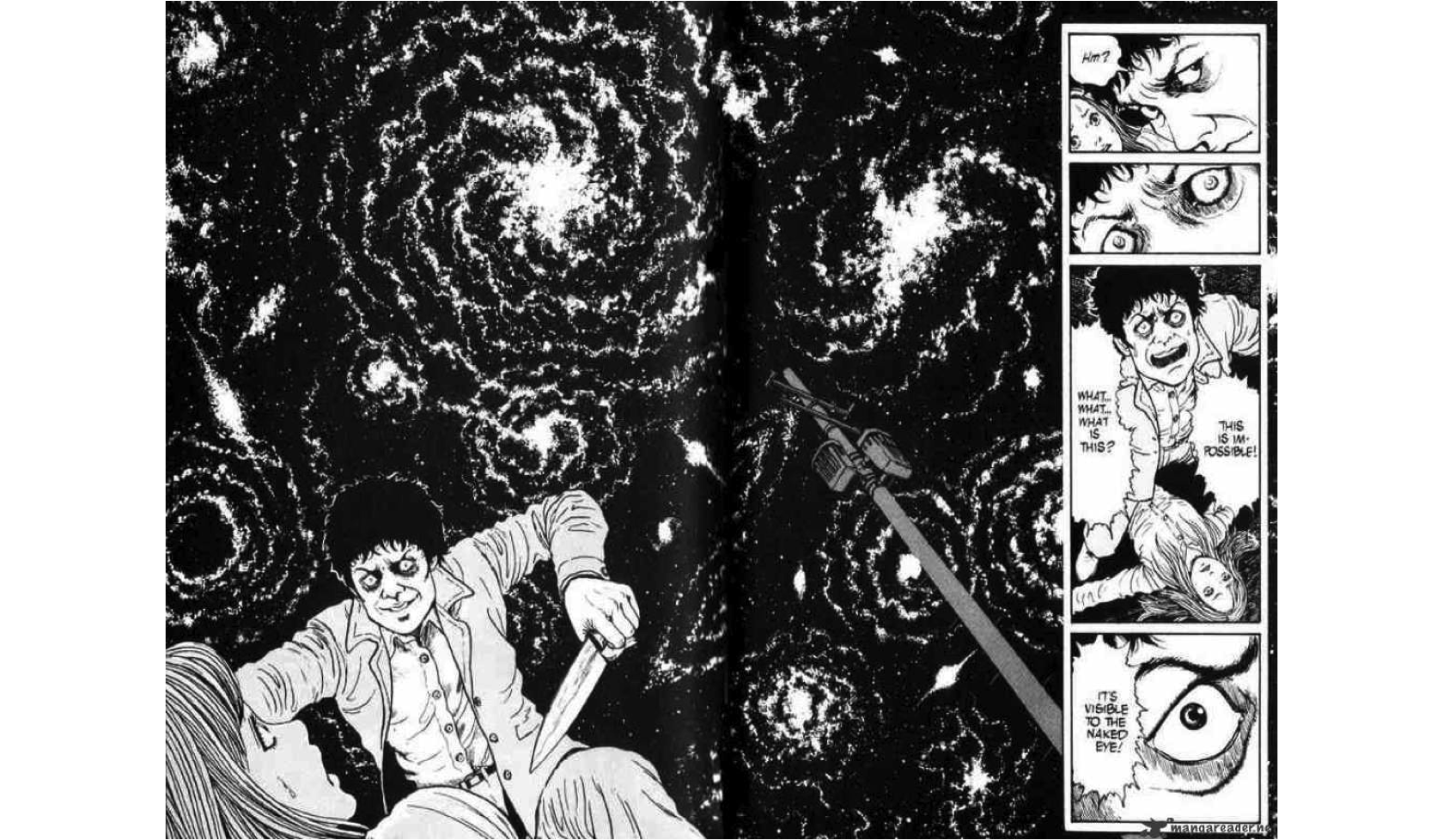

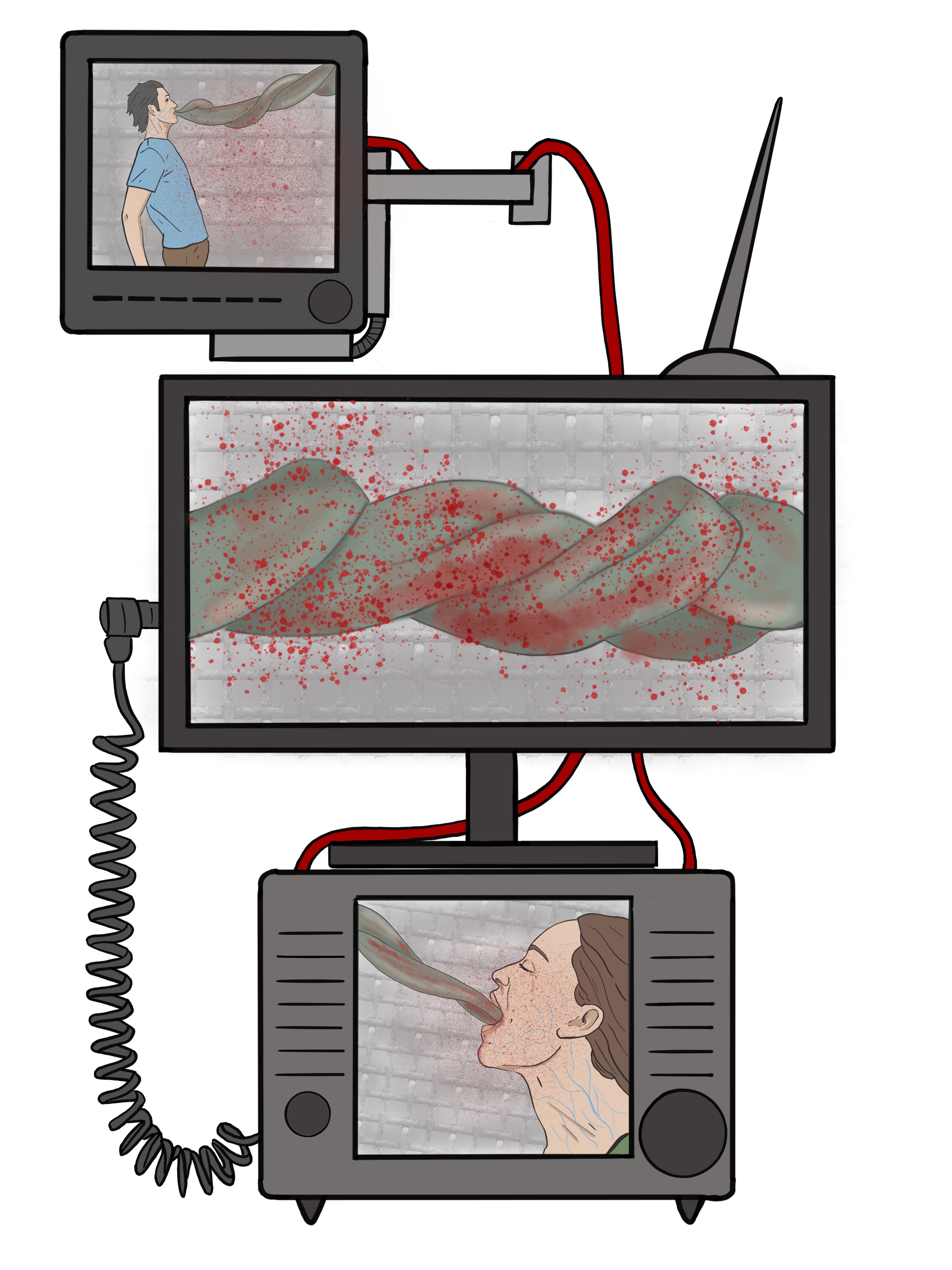

Illustration by Rob Thompson.

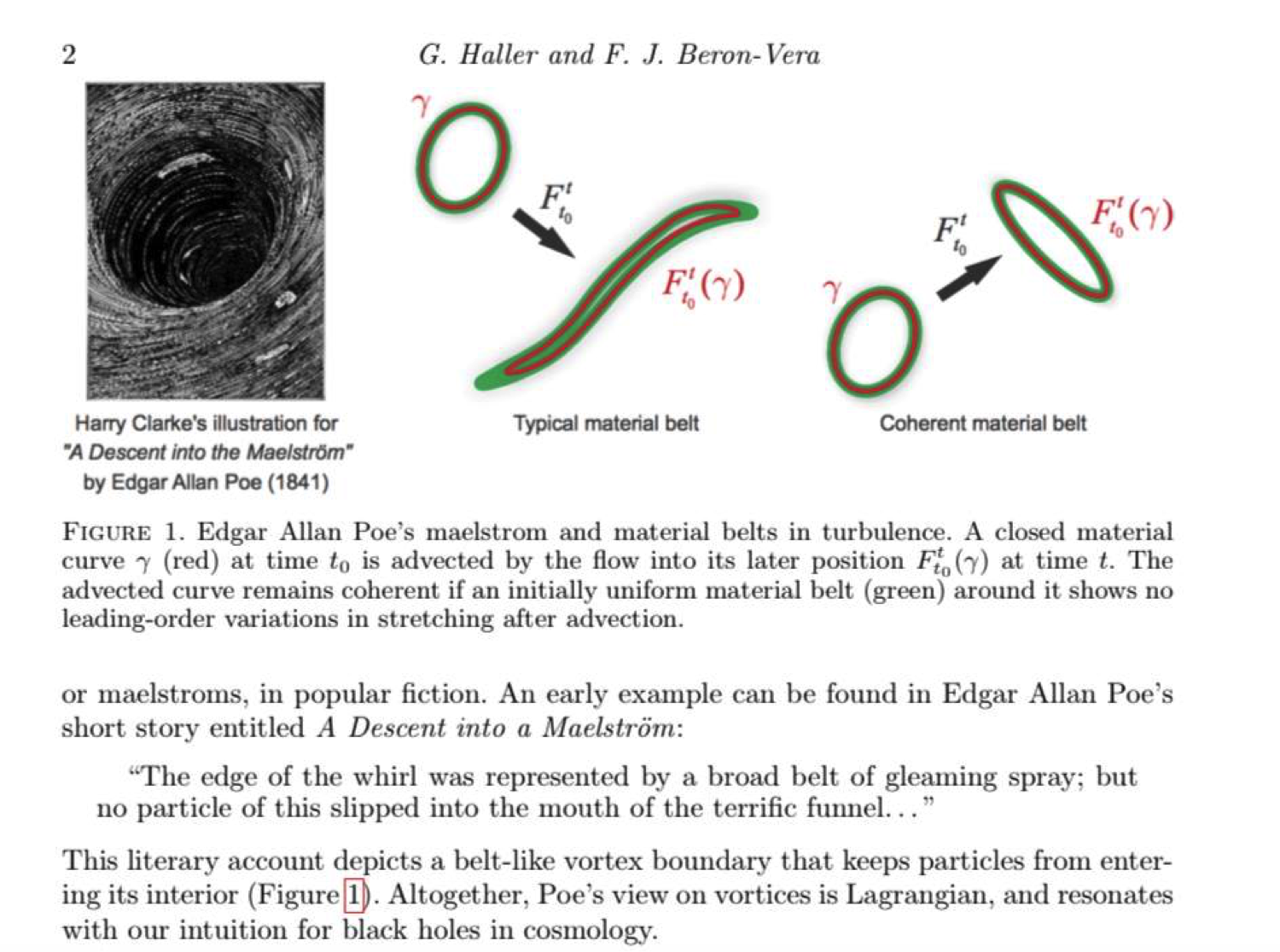

I’ve mentioned the root of the word “sarcophagus;” it was Peter, ironically enough, who told it to me. It’s Greek: it means “flesh eating.” Exactly how that word came to be applied to large stone coffins I’m unsure, but in this case it was quite literally true. Peter was enclosed within a kind of mouth, a great stone mouth, and it…consumed him. The process was not quick. By the time George returned to the house almost a week and a half later, however, it was complete. Sometime in the long excruciation before that point, Peter must have realized that his father was implicated in what was happening to him. It was impossible for him not to be. His father had brought Mr. Gaunt into the house, and then left Peter at his mercy. His beloved father had failed, and his failure was Peter’s death.

It took George longer than I would have expected, almost two full days, to discover Peter’s fate, and to discern the butler’s role in it. When he did so, he punished, as he put it, Mr. Gaunt suitably. He did not tell me what such punishment involved, but he did assure me that it was thorough. Peter’s running away was, obviously, the ruse invented by George to hide his son’s actual fate.

By the time your uncle told me the story I’ve told you, Clarissa had been dead for several years. I hadn’t spoken to her since our phone conversation when Peter first vanished, and, I must confess, she had been absent from my thoughts for quite some time when I stumbled across her obituary on the opposite side of an article a friend in London had clipped and sent me. The obituary stated that she had never recovered from the disappearance of her only son almost two decades prior, and hinted, if I understood its inference, that she had been addicted to antidepressants; although the writer hastened to add that the cause of death had been ruled natural and was under no suspicion from the police.

If George heard the news of his former wife’s death, which I assume he must have, he made no mention of it to me, not even during that last conversation, when so much else was said. Although I hadn’t planned it, we both became quite intoxicated, making our way through the better part of a bottle of Lagavulin after I had put you to bed. The closer I approach to complete intoxication, the nearer I draw to maudlin sentimentality, and it wasn’t long, as I sat beside my older brother looking across the Hudson to Poughkeepsie, the place where we had been born and raised and where our parents were buried, I say it wasn’t long before I told George to stay where he was, I had something for him. Swaying like a sailor on a ship in a heavy sea, I made my way into the house and to my study, where I located the shoebox in which I keep those things that have some measure of sentimental value to me, pictures, mostly, but also the letters that your cousin had sent me, tucked in their envelopes. Returning to the porch, I walked over to George and held them out to him, saying, “Here, take them.”

He did so, a look that was half-bemusement, half-curiosity on his face. “All right,” he said. “What are they?”

“Letters,” I declared.

“I can see that, old man,” he said. “Letters from whom?”

“From Peter,” I said. “From your son. You should have them. I want you to have them.”

“Letters from Peter,” he said.

“Yes,” I said, nodding vigorously.

“I was unaware the two of you had maintained a correspondence.”

“It was after the summer he came to stay with Mother. The two of us hit it off, you know, quite well.”

“As a matter of fact,” George said, “I didn’t know.” He continued to hold the letters out before him, as if he were weighing them. The look on his face had slid into something else.

Inspired by the Scotch, I found the nerve to ask George what I had wanted to ask him for so long: if he ever had received any word, any kind of hint, as to what had become of Peter? His already flushed face reddened more, as if he were embarrassed, caught off-guard, then he laughed and said he knew exactly what had happened to his son. “Exactly,” he repeated, letting the letters fall from his hand like so many pieces of paper.

Despite the alcohol in which I was swimming, I was shocked, which I’m sure my face must have shown. All at once, I wanted to tell George not to say anything more, because I had intuited that I was standing at the doorway to a room I did not wish to enter, for, once I stood within it, I would discover my older brother to be someone—something—I would be unable to bear sitting beside. We were not and had never been as close as popular sentiment tells us siblings should be; we were more friendly acquaintances. It was an acquaintance, however, I had increasingly enjoyed as I grew older, and I believe George’s feelings may have been similar. But my tongue was thick and sluggish in my mouth, and so, as we sat on the back porch, George related the circumstances of his son’s death to me. I listened to him as evening dimmed to night, making no move to switch on the outside lights, holding onto my empty glass as if it were a life-preserver. As his tale progressed, my first thought was that he was indulging in a bizarre joke whose tastelessness was appalling; the more he spoke, however, the more I understood that he believed what he was telling me, and I feared he might be delusional if not outright mad; by the story’s conclusion, I was no longer sure he was mad, and worried that I might be. I was unsure when he stopped talking: his words continued to sound in my ears, overlapping each other. A long interval elapsed during which neither of us spoke and the sound of the crickets was thunderous. At last George said, “Well?”

“Gaunt,” I said. “Who is he?” It was the first thing to leap to mind.

“Gaunt,” he said. “Gaunt was my teacher. I met him when I went to Oxford; the circumstances are not important. He was my master. Once, I should have called him my father.” I can not tell you what the tone of his voice was. “We had a disagreement, which grew into an… altercation, which ended with him inside the stone sarcophagus that had Peter, though not for as long, of course. I released him while there was still enough left to be of service to me. I thought him defeated, no threat to either me or mine, and, I will admit, it amused me to keep him around. I had set what I judged sufficient safeguards against him in place, but he found a way to circumvent them, which I had not thought possible without a tongue. I was in error.”

“Why Peter?” I asked.

“To strike at me, obviously. He had been planning something for quite a length of time. I had some idea of the depth of his hate for me, but I had no idea his determination ran to similar depths. His delight at what Peter had suffered was inestimable. He had written a rather extended description of it, which I believe he thought I would find distressing to read. The stone teeth relentlessly pressing every square inch of flesh, until the skin burst and blood poured out; the agony as the teeth continued through into the muscle, organ, and, eventually, bone; the horror at finding oneself still alive, unable to die even after so much pain: he related all of this with great gusto.

“The sarcophagus, in case you’re interested, I found in eastern Turkey, not, as you might think, Egypt; though I suspect it has its origins there I first read about it in Les mysteres du ver, though the references were highly elliptical, to say the least. It took years, and a small fortune, to locate it. Actually, it’s a rather amusing story: it was being employed as a table by a bookseller, if you can believe it, who had received it as payment for a debt owed him by a local banker, who in turn…”

I listened to George’s account of the sarcophagus’s history, all the while thinking of poor Peter trapped inside it, wrapped in claustrophobic darkness, screaming and pounding on the lid as—what? Although, as I have said, I half-believed the fantastic tale George had told, my belief was only partial. It seemed more likely Peter had suffocated inside the coffin, then Gaunt disposed of the body in such a way that very little, if any, of it remained. When George was done talking, I asked, “What about Peter?”

“What about him?” George answered. “Why, ‘What about Peter’? I’ve already told you, it was too late for me to be able to do anything, even to provide him the kind of half-life Gaunt has, much less successfully restore him. What the sarcophagus takes, it does surrender.”

“He was your son,” I said.

“Yes,” George said. “And?”

“’And’? My God, man, he was your son, and whatever did happen to him, he’s dead and you were responsible for his death, if not directly then through negligence. Doesn’t that mean anything to you?”

“No,” George said, his voice growing brittle. “As I have said, Peter’s death, while unfortunate, was unintentional.”

“But,” I went on, less and less able, it seemed, to match thought to word with any proficiency, “but he was your son.”

“So?” George said. “Am I supposed to be wracked by guilt, afflicted with remorse?”

“Yes,” I said, “yes, you are.”

“I’m not, though. When all is said and done, Peter was more trouble than he was worth. A man in my position—and though you might not believe it, my position is considerable—doing my kind of work, can’t always be worrying about someone else, especially a child. I should have foreseen that when I divorced Clarissa, and let her have him, but I was too concerned with her absolute defeat to make such a rational decision. Even after I knew the depth of my mistake, I balked at surrendering Peter to her because I knew the satisfaction such an admission on my part would give Clarissa. I simply could not bear that. For a time, I deluded myself that Peter would be my apprentice, despite numerous clear indications that he possessed no aptitude of any kind for my art. He was…temperamentally unsuited. It is a shame: there would have been a certain amount of pleasure in passing on my knowledge to my son, to someone of my own blood. That has always been my problem: too sentimental, too emotional. Nonetheless, while I would not have done anything to him myself, I am forced to admit that Peter’s removal from my life has been to the good.”

“You can’t be serious,” I said.

“I am.”

“Then you’re a monster.”

“To you, perhaps,” he said.

“You’re mad,” I said.

“No, I’m not,” he said, and from the sharp tone of his voice, I could tell I had touched a nerve, so I repeated myself, adding, “Do you honestly believe you’re some kind of great and powerful magician? or do you prefer to be called a sorcerer? Perhaps you’re a wizard? a warlock? an alchemist? No, they worked with chemicals; I don’t suppose that would be you. Do you really expect me to accept that tall butler as some kind of supernatural creature, an animated skeleton? I won’t ask where you obtained his face and hands: I’m sure Jenner’s has a special section for the black arts.” I went on like this for several minutes, pouring out my scorn on George, feeling the anger radiating from him. I did not care: I was angry myself, furious, filled with more rage than ever before or ever after, for that matter.

When I was through, or when I had paused, anyway, George asked, “Could you fetch me a glass of water?”

“Excuse me?” I said.

He repeated his request: “Could I have a glass of water?” explaining, “All this conversation has left my throat somewhat parched.”

Your grandmother’s emphasis on good manners, no matter what the situation, caught me off guard, and despite myself I heard my voice saying, “Of course,” as I set down my glass, stood, and made my way across the unlit porch to the back door. “Can I get you anything else?” I added, trying to sound as scornful as I felt.

“The water will be fine.”

I opened the back door, stepped into the house, and was someplace else. Instead of the kitchen, I was standing at one end of a long room lit by globed lights depending from a slanted ceiling. Short bookcases filled to bursting with books, scrolls, and an occasional stone tablet jostled with one another for space along the walls, while tables piled high with goblets, candles, boxes, rows of jars, models, took up the floor. I saw paintings crowding the walls, including the Bosch I described to you, and elaborate symbols drawn on the floor. At the other end of the room, a bulky stone sarcophagus with a fierce face reclined against a wall. Behind me, through the open door whose handle I still grasped, I could hear the crickets; in front of me, through the room’s curtained windows, I could hear the sound of distant traffic, of brakes squealing and horns blowing. I stood gazing at the room I understood to be my brother’s study, and then I felt the hand on my shoulder. Initially, I thought it was George, but when he called, “Is my water coming?” I realized he had not left his seat. Through my shirt, the hand felt wrong: at once too light and too hard, more like wood than flesh. The faintest odor of dust, and beneath it, something foul, filled my nostrils; the sound of a baby’s rattle being turned, slowly, filled my ears. I heard another sound, the whisper of sand blowing across a stone floor, and realized it was whatever was behind me—but I knew what it was—speaking, bringing speech from across what seemed a great distance. It spoke one word, “Yes,” drawing it out into a long sigh that did not stop so much as fade away: Yyyeeeeeessssssss….

“I say,” George said, “where’s my water?”