John Langan in his natural environment

***

Hi John, and thanks so much for agreeing to an interview for our readers.

Thanks very much for having me, Sean.

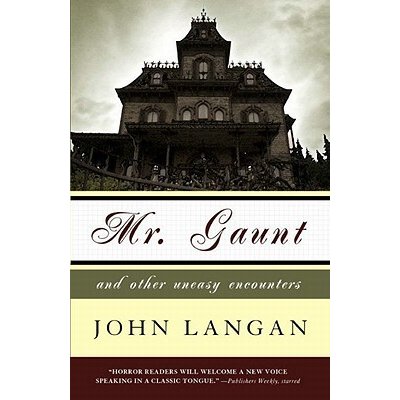

I’m deeply impressed by both your inaugural collection Mr. Gaunt (2008) and the more recent The Wide, Carnivorous Sky (2013.) I’d like to ask you a few general questions about these collections, to begin with.

I’m struck by the aptitude of the sub-titles appended to both collections. Mr. Gaunt bears the subtitle, “and other uneasy encounters.” Why “uneasy” (as opposed to, say, unsettling, or terrifying, or some other adjective)?

My first collection was published before I had been thinking I would bring out a book of stories. I figured I’d have to wait for a novel (or two) to establish me for a wider audience, and then I’d try a collection. When I had the chance to publish the collection, though, I took it. I figured I should title the book after what was the best known of my early stores, but Mr. Gaunt seemed too short—that, and I didn’t want to create the impression I’d expanded the story into a novel. A subtitle seemed like a good way to solve this problem. I liked the idea of thinking about the stories as encounters, both in terms of their plot action, and of the reader’s interaction with them. I think it’s one of Eliot’s poems where the speaker describes himself at the end as “no longer at ease.” I liked the idea of uneasiness as a way to describe the tenor of the stories’ plots and the effect I hoped they’d have on the reader. (Also, let’s face it: you call your stories terrifying, and you’re inviting a critic to tell you they aren’t.)

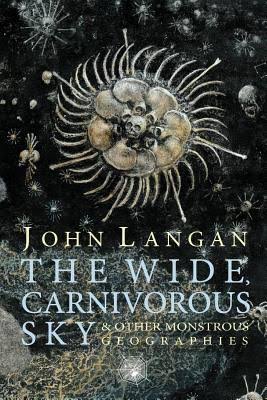

The Wide, Carnivorous Sky, on the other hand, bears the sub-title “& Other Monstrous Geographies.” What inspired this subtitle, and how is “monstrous geography” an important conceptual thread running through the stories in this collection?

Actually, the original title of my second collection was Technicolor and Other Revelations. I had followed the logic I’d used in naming my first collection and chosen the story that I was best known for to serve as the title. I thought the idea of revelation was a good way to conceptualize the experiences my characters had over the course of their narratives. My publisher, however, was worried that Technicolor was a copyrighted term, and asked if we couldn’t change the title to The Wide, Carnivorous Sky? I decided that my original subtitle didn’t work as well with this new title, so I tried to come up with something that fit better. I thought the idea of the sky suggested large spaces, which led me to geography, which led to geographies. Since each story took place in its own, different setting, the word seemed like a decent fit, but I also liked the idea of conceiving the space of each story as a geography. Monstrous was perhaps a bit on the nose, but since the book was also a kind of catalogue of traditional monsters, I thought it worked. Now that I’m writing this, it occurs to me that, since the stories play with narrative form, you might say that gives the word monstrous an additional application.

One of the differences between these two collections is that the stories in Mr. Gaunt are treated more as framed narratives, whereas those in The Wide, Carnivorous Sky are more varied – the second collection, in short, covers more ground, and the stories therein show a much greater diversity of voice and style. How would you characterize the evolution you underwent in the intervening five years between these two collections?

I think the major development in my writing actually occurred in the midst of the stories that constitute Mr. Gaunt. The first drafts of my first two published stories, “On Skua Island” and “Mr. Gaunt,” were written within a few months of one another, and while I subsequently worked revising “Mr. Gaunt” on and off for almost a year after I wrote it, its Jamesian orientation was already in place. By the time I came to write “Tutorial,” I was trying to work in a more explicitly meta-fictional mode. Then, after “Tutorial,” I took the next couple of years to write my first novel, House of Windows, in which I indulged my Jamesian obsessions to the hilt. The story I wrote after that, “Episode Seven: Last Stand Against the Pack in the Kingdom of the Purple Flowers,” was an extravaganza that drew on writers I’d mentioned in “Tutorial,” such as Samuel Delany, as well as Stephen King, but whose example I hadn’t yet engaged. Shortly thereafter, I wrote “How the Day Runs Down,” my zombified Our Town, and “Technicolor,” my Poe phantasia. I suppose what was happening was an increased willingness on my part to try different approaches to narrative construction.

Are there any marked shifts you can pin-point in your approach to writing fiction?

In terms of my work habits—writing every day, say—I remained fairly consistent. Where I think I may have developed was in my comfort with trying different narrative structures, as well as with being willing to engage the material of horror in more direct and intensive ways.

Are there any major literary influences that either became foregrounded or receded for you during this period of time?

My early stories and first novel draw quite explicitly on the examples of Henry James and Charles Dickens; though I also recognize the ghosts of figures from Robert E. Howard to John Fowles to Peter Straub lurking within them. James and Dickens have remained important to me, but I think they’ve probably receded a bit, while Faulkner and Robert Penn Warren have moved a bit more to the foreground. Straub has remained essential to me, and I continue to appreciate how important Stephen King has been to all of my work.

The ghost of Henry James seems to loom large over many of the stories in Mr. Gaunt – most notably the titular tale, one of whose narrators is a James scholar, but also through “On Skua Island,” “Tutorial” and others. Why and how did James’s shadow come to fall so extensively over this collection?

Since reading “The Jolly Corner” during my sophomore year of college, I’ve been a big fan of James. I found in his work a richness of language, of art, that seemed so much more profound to me than much of the rest of what I was reading. (The same thing was true of Faulkner.) I turned to James’s example as an alternative to certain trends in contemporary literature—the kind of flatness of language that I associate with more naturalistically inflected fiction. In a way, I think what I was responding to in James was analogous to what other readers have responded to in Lovecraft, or Ligotti: that sense of indulgence in language, of delight in the extremes to which style can be taken. It’s a welcome rejoinder to the excessive sway varieties of minimalism have exercised on literature in general. In the case of James, I also loved that so much of his work fell under the banner of the supernatural; his example helped to calm my lingering anxieties about the literariness (or lack thereof) of working in the horror field. I loved the way that he anatomized the processes of his characters’ consciousnesses, of the ebb and flow of their perceptions. You saw, in a story like “The Jolly Corner” or The Turn of the Screw, the way in which his characters’ reactions to the supernatural changed over time, gathered weight and resonance. I thought his example remained compellingly relevant to writing in the horror field.

In a recent podcast interview with Scott Nicolay, you make some interesting remarks about Shirley Jackson’s achievement, and particularly her pre-Hill House novel, The Sundial. Can you talk a little more about your fascination for this novel, in particular?

I’m pretty sure it was Stephen King who steered me in the direction of The Sundial through his praise of it in Danse Macabre. I was fascinated by the novel’s observance of the Aristotlean unities of time and space, and the way in which it lensed an apocalyptic narrative through the experience of a single family—even as it maintained doubt as to whether there was any apocalypse going on, at all. It’s an astonishing performance, one I wish more people knew.

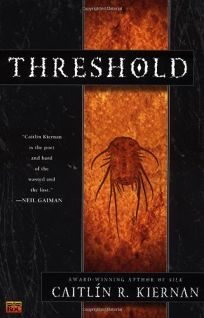

The title of The Wide, Carnivorous Sky is derived from a story by Caitlin R. Kiernan. To what extent would you say Kiernan has been an influence on you? Can you share some of your thoughts on her work, and its relationship to your own?

When I read Caitlin Kiernan’s second novel, Threshold, I was absolutely floored by it. It remains, in my estimation, one of the great novels of supernatural horror of the first decade of the twenty-first century. I hold her novella, “Onion,” in the same regard. What she managed to do with her first five novels and many of her early stories, braiding them together into a greater narrative, still strikes me as a remarkable achievement, one that I think deserves more critical attention. I don’t perceive a direct influence of her work on mine; I tend to think of her more as a contemporary writer who has done amazing work within the field of fantastic fiction.

Speaking of influence and literary precursors, while you are often associated with Lovecraftian horror, you also generally avoid making overt allusions or homages to Lovecraft’s fictions in your own. Is this something you intentionally avoid? Do you have any thoughts on the super-abundance of Lovecraft-homage fiction out there? Are there any particular writers who, to your mind, manage to use this approach to powerful effect?

I wouldn’t say it’s been intentional so much as a case of Lovecraft being one of those writers I came to somewhat later than seems to be the norm for a lot of horror writers. I knew his name from Danse Macabre, among other places, but the only Lovecraft I read when I was in my early teens was The Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath and a few of the stories associated with Randolph Carter. Those left me unmoved. Later on, at the end of my teens/beginning of the my twenties, I got a copy of the old Del Rey selection of Lovecraft’s greatest hits, Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre, and that was when I started to read Lovecraft’s work in earnest. The Penguin classics editions of his stories, edited by S.T. Joshi, appeared a few years later, and Joshi’s extensive annotations deepened my appreciation of Lovecraft’s achievement. At this point, I think I’ve delivered more conference presentations on Lovecraft’s fiction than I have on anyone else’s work, thanks in part to the annual Lovecraft Forum at SUNY New Paltz; while there’s about a hundred and sixty pages of what was going to be a dissertation on Lovecraft and Robert Browning hibernating on my computer. At this point, I suppose my fiction has appeared in enough Lovecraft-themed anthologies for me to be lumped in with the Lovecraftian crowd, but I’m not sure the fit is all that good. For a while, there, whenever I would sit down to write a piece of Lovecraft-inflected fiction, I would spend as much of the story working in mimetic naturalist mode (i.e. “The Shallows,” “Children of the Fang”). Actually, I think I still tend to do that kind of thing, to pull the cosmic back to the personal. I want to attribute my failure to connect with Lovecraft in what I guess you might call an emotional way to not having read him until I was older, but I read M.R. James’s stories later still, and loved them, so it may be as much a matter of the quirks of my personality.

As for the superabundance of Lovecraft-inspired fiction currently available: I think it’s attributable on at least some level to the cultural clout Lovecraft has gained this past decade or so, from those Penguin editions to the Library of America selection of his work, but I also think it has something to do with a number of writers working in the field Lovecraft plowed and raising something more than mere pastiche. Of course, there’s an economic imperative on the part of publishers big and small: Lovecraft, and especially Cthulhu, sells—it really does seem to occupy the same niche zombies did a few years ago, and vampires before that.

And as far as writers using cosmic horror to powerful effect: among my contemporaries, I can’t think of anyone who’s worked with cosmic horror more powerfully than Laird Barron. Especially in stories such as “Hallucigenia,” “Mysterium Tremendum,” and “The Men from Porlock,” as well as his novel, The Croning, he’s re-invented the field for a new generation. I also think Gemma Files has written some wonderfully strange cosmic horror stories, and Richard Gavin deserves mention for engaging the more visionary aspects of the field in his stories.

In a blog post published on Aug 12, 2015, you discuss your relationship with your former professor and mentor, noted Lovecraft scholar Robert Waugh, and single out in particular his essay on Lovecraft, “The Subway and the Shoggoth,” noting that “the essay – and Bob’s critical work in general – has served as a model for my own critical efforts.” Can you tell us a little more about your relationship with Waugh, how his approach has affected your work as a scholar, as a teacher, or as a writer of fiction?

Bob Waugh is one of my oldest and dearest friends and teachers. I met him during my the first semester of my freshman year at SUNY New Paltz, and the inaugural H.P. Lovecraft Forum, one of the events that helped reassure me I had made the right choice in deciding to attend New Paltz. The following semester, he was my professor for my Honors English composition class, in which we read selections from Poe’s stories, among other things. Bob is something like my Platonic ideal of a college professor: he seems to have read everything under the sun; he can read most of the major European languages (though with a dictionary, he would hasten to add); he has a knowledge of history, music, and art that’s almost as extensive as his literary knowledge. He’s the opposite of that type that’s cropped up in academia the last twenty five years or so, the specialist. I think it’s in my critical work that I find Bob’s influence the most evident. Bob has always combined a close, almost monkish attention to textual detail with his awareness of the larger contexts of the writer’s biography, cultural context, and general literary history. Thus, he’s placed Lovecraft in relation to Pope, Keats, Leopardi, and Pound, among others, arguing for Lovecraft as part of a kind of idiosyncratic tradition in western literature. I still think his two books on Lovecraft, The Monster in the Mirror and A Monster of Voices, are the best critical studies anyone has done of him, and I recommend them wholeheartedly.

Waugh’s essay tackles in a particularly incisive way one aspect of the relationship between Lovecraft’s literary achievement and his racist and xenophobic views, something that Lovecraft’s critics and admirers have wrestled with in a variety of different ways, particularly over the last few years. Do you have any further thoughts on the relationship between Lovecraft’s literary achievements, his xenophobia and views on race or sexuality, and the consequences of both for his continuing cultural legacy?

What I admire about Bob’s essay is the way it engages the relationship between Lovecraft’s more offensive views and his fiction first by analyzing the language both discourses have in common and then by using the fiction as a way to read those views. It’s the opposite of what a lot of the more recent responses to Lovecraft’s work have done, i.e. treat the fiction as essentially an allegory—and a simple one, at that—for his assorted prejudices. Bob’s essay is able to get at something of the complexity of Lovecraft’s writing without looking away from or excusing its troubling aspects. I’m not sure there’s more for me to add to Bob’s essay, except to repeat my desire that both Lovecraft’s detractors and apologists might read it. In the long run, I’m not sure how our knowledge of Lovecraft’s racism and xenophobia will affect the continued status of his literary reputation. We’ve been able to tolerate a lot from a lot of writers. I imagine it will have more to do with how well his fiction succeeds with readers over time. As long as the stories find an appreciative audience, then they’ll endure.

You’ve often cited Stephen King as an influence, even describing him as “part of my writing DNA in a way distinct from almost any other writer.” Can you elaborate on what you meant by this?

Stephen King was the first writer I encountered whose work inspired in me the overwhelming urge to imitate what I had read. My reaction was so strong it felt as if it was coming from outside myself, as if the text was choosing me. To say that King influenced me feels like an understatement. His work enveloped me, compelled me, fundamentally shaped the way I thought about narrative construction, character representation.

Looking back on the experience, I’m reminded of Althusser’s notion of hailing or interpellation, the process by which your internalization of certain socio-cultural dynamics causes you to feel that something outside yourself is constituting you as part of an ideological structure, giving you your identity. Just as Althusser borrowed certain notions from psychoanalysis in his revision of Marx, it may be that this notion of his should be borrowed and applied to the psychology of creativity. Certainly, there are cases where other writers have described something similar: Ramsey Campbell speaks of his first encounter with Lovecraft’s fiction in these terms, as does Lovecraft his experience of Poe. For a while, I thought that Harold Bloom’s Anxiety of Influence best accounted for this kind of experience, but I’ve since found that Bloom’s theories are much more limited in their applications and implications than he would like them to be, and indeed, when all is said and done, may best be applied to Bloom, himself.

To return to the original subject of your question, though: when all is said and done, I think the deep structure of my work continues to owe as much if not more to the example of Stephen King’s fiction, as my thinking about the horror field does to Danse Macabre, than to any other single writer.

Can you tell us a little about when and how you first discovered his fiction, and about the ways in which it may have influenced you?

I was aware of King’s fiction for some time before I actually read it; the foil-embossed covers of books like ‘Salem’s Lot and The Shining stared at me from the display stands at the front of the local Waldenbooks and Book & Record stores. The first story of King’s I read was “Battleground,” which was reprinted in a slightly-edited form in a monthly-magazine that my seventh grade reading class got. I was impressed with the idea of an army of toys hunting a hitman, but otherwise, it didn’t have a great effect on me. Nor did the first novel of King’s I read, Cujo, during the summer between eighth and ninth grade. A few months later, though, the paperback of Christine was released, and something about the book made me pick it up. Was it that I knew this book had a more explicitly supernatural situation than Cujo? Was it that its characters were high school students, as was I, now? I can’t quite remember. In any event, that was the book that produced in me the response I described in my previous answer. After that, I had to read everything King had written.

And I had to write, too, my own horror stories. I have no doubt that King’s example permeates most if not all of what I’ve written, but where I remain most aware of it on the local level is in the pacing of his fiction, his willingness to let the narrative unfold in its own time. This could lead to interminable stories, if it weren’t complemented by his ability to construct a compelling narrative voice. On a more global level, the integrity with which King treated the writing of horror fiction made a tremendous impression on me (I recognized the same quality in Laird Barron, when I began corresponding with him, years later), as did his extensive knowledge of the horror field, and his willingness to engage the examples of the writers who’d come before him.

One of the best recent essays I’ve read on King’s fiction is your contribution to the collection Lovecraft and Influence, edited by Robert Waugh. Have you published, or are you planning to publish, more critical work on King’s fiction? What inspired you to approach King’s story “Graveyard Shift” through the troubled aesthetic discourse of the sublime? (A discourse that also seems to me central to your novella, “Laocoon, or the Singularity.”)

I don’t have any immediate plans to do more critical work on King; if I did, it would expand the essay you mention to consider the influence of Lovecraft’s “The Colour Out of Space” on King’s fiction—which, as far as I can tell, is the single piece of Lovecraft’s that casts the longest shadow over King’s work. Almost every time King turns to something like science fiction, especially in his novels The Tommyknockers, Dreamcatcher, and From a Buick Eight, he comes back to “The Colour Out of Space.” The essay on “Graveyard Shift” and “The Rats in the Walls” grew out of a paper I delivered at one of the annual Lovecraft Forums at SUNY New Paltz. For a number of years, each time the Forum drew near, I started thinking about Lovecraft’s influence on a different writer, from Fritz Leiber to Peter Straub to T.E.D. Klein to, of course, King. Possibly—probably as a result of a conversation with Bob Waugh about Lovecraft and King—it occurred to me that “Graveyard Shift” was in fact King’s response to and rewriting of “Rats in the Walls.” My use of the idea of the sublime—and in King’s case, what I called the animal sublime—emerged from an attempt to differentiate the two stories’ ultimate effects. It continues to seem to me that, especially when discussing cosmic horror fiction, the notion of the sublime remains indispensable, and if King’s story doesn’t employ the idea in quite the same way as does Lovecraft’s, it nonetheless reaches for something analogous in its vision of the animal.

In a recent PstD interview, David Nickle went so far as to call King “the John Milton of modern horror.” However tongue-in-cheek, do you think there is merit in this analogy?

I appreciate David’s comparison as a way to try to get at King’s stature and sway within the horror field, but at the risk of dissecting a joke and ruining it, I’d suggest another figure: Geoffrey Chaucer, I think. The problem with the Milton analogy is that he’s an exhaustive poet, one of those writers who uses up all the oxygen in the room for a generation or two. It takes English literature over a hundred years to produce another great epic poem, Wordsworth’s Prelude, and even then, Wordsworth has to turn to the subject of his own interior growth because Milton has so dominated possible historical and mythological topics (Yes, there’s Pope’s Dunciad in between, but that’s a strange, satiric work that doesn’t even try to complete with Milton.) I don’t see King as having used up the horror field in the same way; rather, I view him as having opened up its possibilities more thoroughly even than Lovecraft. It’s for that reason that I reach to Chaucer for my preferred comparison, because his work (particularly The Canterbury Tales, of course) represents an opening up of possibility for a writer working in English. In the same way, Stephen King expands the possibilities for writers of horror fiction.

One exception to your tendency to avoid overt Lovecraft allusions in your stories occurs in “Mr. Gaunt” (reprinted here) whose sinister, esoteric scholar is said to have translated a Medieval text called Les Mysteres du Ver (page 59). The title is a French translation of Des Vermiis Mysteris, or Mysteries of the Worm, a nefarious grimoire invented by Robert Bloch for his Lovecraftian tale of the same name. What are your thoughts on the advantages and disadvantages of drawing on notable “Mythos” titles such as this? Why did you decide to include that fictional tome, in particular, in the story, rather than, say, a Lovecraftian coinage like the Necronomicon?

As the character of George Farange, the sinister, esoteric scholar, solidified in my mind, I thought it would be a nice touch to have him translate some kind of occult text. I could have invented my own, but I liked the idea of tying him into the library of weird tomes that’s been assembling since Chambers’s King in Yellow. The Necronomicon seemed a bit too much on the nose, its ubiquity likely to jolt the reader out of the story. I thought about Howard’s invention, the Unaussprechlichlen Kulten, but since I wasn’t dealing with nameless cults, passed on it in favor of the Mysteries of the Worm, which seemed to tie in more directly to the story’s concern with the corruption of the body. Even as I wanted to invoke the earlier book, though, I also wanted to distinguish my use of it, and thus the French edition. I thought this would simultaneously acknowledge the tradition in which I was working, and differentiate my take on it.

Speaking of “Mr. Gaunt,” can you tell us a little about the origins, inspiration, context, and subsequent textual history of this story?

If I may be excused for doing so, I’ll quote from the (edited) story notes in my first collection: This was a difficult story. I wrote the first draft of it over the course of a month and a half in the summer of 2000. Both the length of time I spent writing and the length of the finished story were a surprise. When I first conceived it, I imagined “Mr. Gaunt” done in under two weeks and twenty pages. Having completed “On Skua Island” I felt the urge to write another short story. I had been investigating publishing possibilities for “On Skua Island” and discovered that most magazines wanted relatively short stories. Before I had the faintest idea what my next story was going to be about, I decided I should write something that I would be able to place with a magazine more easily than the almost fifty page “Skua Island.” Needless to say, this did not happen.

I had discussed possible ideas for my next story with Bob Waugh, at whose house on Cape Cod I had written “On Skua Island.” The theme of our conversation, I suppose, was Monsters Who Might Be Rehabilitated. During the course of it, I suggested the skeleton, whose simplicity I found appealing. Bob agreed that the skeleton was intriguing, but thought it brushed the edges of a mordant humor that would undo any effect of horror. “It’s too witty,” he said. I did not disagree with his assessment, but took it as a challenge.

That challenge floated just under the surface of my brain until I had lunch with my then-nine-year-old son, Nicholas, visiting from Maryland. Recently, Nick had written and illustrated his own short book for school, which told the story of a pair of friends who discover a magic sword; now, he was contemplating his next project, whose plot he had mapped out and needed only to write (a situation with which I can sympathize). It would relate the tale of a Spanish knight, (“Like Don Quixote,” he said), who would meet his end at the hands of a monstrous skeleton even as he dispatched it. “That’s funny,” I said when he had finished his summary, “I was thinking about writing about a skeleton, too. Maybe I will.”

The picture of a small boy trapped in a room with the skeleton formed in my mind soon thereafter. Although I could envision the room, which would be walled with bookcases, and contain a large varnished table and a globe, I could see little else. Despite my initial planning, I did not commence work on “Mr. Gaunt” for another couple of weeks. I put the skeleton aside in favor of the witch, who seemed a more promising subject, only to find I had no better idea what might be done with her. Frustrated, I took a long walk one Saturday afternoon with my wife up a local my wife that skirts a stream before climbing a steep hill. Along the way, while stopping to admire old farmhouses set back from the road, horses grazing in pastures, birds flitting from bush to telephone wire to tree, we discussed possibilities for my next story. Nothing sounded right. It was only when we were almost back at the car that the kernel of “Mr. Gaunt” suggested itself. We had been talking, on and off, about the excess of witches in children’s stories, and as we returned to that fact yet again, I suddenly had the thought that you might write a story in which a fairy tale was revisited and given an adult gloss. As that prospect occurred to me, it was followed almost immediately by the realization that this was how I could approach the skeleton. I sketched the idea to Fiona: you could write a story in which you recited parts of a children’s fairy tale, and then commented on those parts. “Like Pale Fire,” I said.

The first page of the story already written mentally, I began writing—typing, actually: for what it’s worth, this was one of the few stories I began working on on the computer. (Subsequently, I shuttled back and forth between computer and yellow legal pad.) In a relatively short span of time, maybe two weeks, I saw that what was intended to be twenty pages would exceed that limit. I had intended to give and gloss more of the fairy tale than was emerging in the story, but the gloss was running away with the story, the narrator establishing himself more firmly with every (long) sentence. I wrestled with the work, trying not to let my narrator take me on too many lengthy digressions, frequently having to double back to an earlier point in the story and begin again. Through those false leads, however, I learned quite a bit about the man telling this tale; indeed, I knew more about him than any other narrator I had employed up to this point. Over the course of my writing, the focus of the story changed, as I came to see that it was not so much Mr. Gaunt, whose name I hit on immediately, as it was George who was the story’s true villain. By the time I came to what had originally seemed the story’s climax, Peter’s being chased through the streets of Edinburgh by the skeleton, I knew that it was not in fact the story’s apex, or that it was only the first. The real high point was to occur on the narrator’s back porch.

Early on in “Mr. Gaunt,” I knew the narrator was a James scholar. I also knew that I would include references to What Maisie Knew as a way to extend the narrative’s concerns, particularly that with the relations between parents and children and with children who are forced to be party to things they should not be. As my work proceeded, I recognized that this narrator, in his concern with the act of telling his tale, in his intrusions into his story, was a more explicitly Jamesian narrator than the narrator of “On Skua Island.” The story became increasingly caught up with voice, with voice creating character through speaking itself. Like a lot of horror stories, it’s concerned with the voices of the dead.

When I started “Mr. Gaunt,” I saw myself as attempting to follow up on the experimentation I had begun with “On Skua Island.” By the time I was done, the story did not have the feeling of a bold step forward that marked “On Skua Island;” rather, I thought of it as refining certain techniques I had played with previously. At the risk of sounding too self-satisfied, now that I have somewhat more distance from it, I see that “Mr. Gaunt” is a bit more experimental than I was aware.

Lest I sound too pleased with myself, however, I should mention that the first magazine to which I sent “Mr. Gaunt” wasted no time in rejecting the story. The brief note they sent to me reproached the story for being “murky” and suggested I really needed to read Strunk & White’s Elements of Style. Upon receiving the rejection, I told myself it was just as well: had “On Skua Island” and “Mr. Gaunt” both been accepted for publication, it would have been extremely difficult for me to maintain a real focus on my academic work. However it would be another full year before I returned to “Mr. Gaunt.” The following Christmas, I brought a copy of the story with me when Fiona and I visited her family in Scotland; she read the story attentively and offered an array of perceptive suggestions for how I might improve it. I made some revisions during that trip, then largely abandoned the story until the following summer, when I sat down to the computer and substantially revised the story, adding what are now its first and third parts, bracketing my original tale, giving it more context through the third-person story of the narrator’s son. I sent it out to Fantasy & Science Fiction, and, once again, Gordon Van Gelder sent me a letter of acceptance and a check.

That was not, however, the end of my work on this story. Gordon was unhappy with the ending as I had written it, and his complaint was a valid one. For several weeks after the story had been accepted, I tinkered with its closing scene, arriving at and developing an ending that I thought was more satisfying and e-mailing it to Gordon, who would reply a day or two later with an e-mail stating that this was better, yes, but still not all the way there. It took me three tries to get it right; to the very end, this story would not come easily.

Once it was published, however, the story was very well-received. Writing in Locus, Nick Gevers gave “Mr. Gaunt” an astute, appreciative review. The story was nominated for the International Horror Guild Award, and was reprinted in a year’s best fantasy anthology, which drew another fine review for it from Gary Wolfe, also in Locus. For years, this story, its success, loomed over my subsequent writing; I worried that with it, I’d peaked as a writer. I’ve since gotten over that, but it still seems to me an early high point in my fiction.

The story’s use of Egyptian necromancy links it to popular late 19th century Gothic fictions including Richard Marsh’s The Beetle and Conan Doyle’s “Lot 249.” More overtly, the story “On Skua Island” from the same collection is a horror tale involving mummies. Despite the popularity of the mummy as an icon of nineteenth century Gothic fiction and Golden Age horror film, there is a notable dearth of mummies in more recent and contemporary horror. Why do you think this is?

I think my use of Egyptian materials in both these stories owed a great deal to my academic study at the time, which was focused on Victorian literature. The Victorians were, of course, fascinated by the ancient Egyptians. In part, this was because of the discovery of the Rosetta stone, which allowed them to translate Egyptian hieroglyphics, which in turn allowed them a kind of access to ancient Egyptian culture they hadn’t had before. I suppose you can see that event feeding into the developing discipline of archaeology, which led to the excavation of so many ancient Egyptian structures. Needless to say, all of this, from the discovery of the Rosetta stone to the unearthing of King Tut’s tomb, was part and parcel of Britain’s colonial enterprise in Egypt, a chapter in the U.K.’s history that is viewed now in a much more critical light. I would guess that it’s this shift in perspective that accounts for the decline of the traditional mummy in recent horror fiction and film.

Have there been any recent ancient-Egypt-themed (or mummy-centric) fictions that have captured your interest? Are there any older fictions (or films) that use these tropes in a way that particularly impressed you?

While I enjoyed Stephen Sommers’s The Mummy and The Mummy Returns, those films—although borrowing some plot details from the 1932 movie—had more in common with the Indiana Jones franchise than they did with older mummy narratives. I think that Don Coscarelli’s Bubba Ho-Tep (adapted, of course, from the story by Joe Lansdale) is probably the best of recent mummy films, the one that’s able to take the figure of the mummy and do something interesting with it. In terms of older works, I find that Conan Doyle’s mummy stories retain a lot of their creepy potency; though I think that the definitive mummy story, for me, remains the ’32 film. Boris Karloff’s resurrected Egyptian priest/necromancer is one of his finer performances, and the film’s plot is nicely understated. In later film versions of the monster, it becomes little more than a juggernaut in bandages, which can be frightening, but lacks the weird depths of the original.

With these stories, were you setting out with the deliberate intention of resurrecting (pun intended) an older trope of horror fiction, or was that incidental to your intentions with the story?

Yes, it was absolutely intentional on my part. When I returned to writing horror fiction, I did so through writing an early draft of what would become my werewolf story, “The Revel.” It wasn’t until after I had finished my next story, “On Skua Island,” though, that I realized I could make my way through the traditional horror monsters/tropes. Despite having read a great deal in the field, I was still finding my footing as a writer of it, and from this perspective, focusing on a well-established figure such as the werewolf or mummy gave me a frame to build my story around, since the traditional monsters tend to come trailing individual narrative details with them. This gave me a great deal to play with in my own stories. As of this writing, I’ve made my way through the werewolf and mummy, as well as the zombie (four times), the vampire (three times), the ghoul, the ghost, a number of Lovecraft’s creations, the cursed object (and its accompanying exorcism), kaiju (twice), and the manticore, and I have plans for the gill-man and Frankenstein’s monster. Oh, and mole-men: lately, I’ve been writing a lot of stories about mole-men.

Like “Mr Gaunt” and many of the other stories in that collection, your first novel, House of Windows (2009) is infused by your fascination for and study of Victorian literature. Narrated by a young writer, also a new father, who is in turn told a haunting tale by an attractive widow during a weekend retreat on Cape Cod, it circulates around the apparent haunting and mysterious disappearance of a Victorian literature scholar who specializes in Charles Dickens. These days, Dickens’s name rarely comes up in conversation in horror and weird fictional circles, it seems. What can you tell us about Dickens’s importance for you, about his legacy for Gothic and supernatural fiction?

The first time I read Dickens, I hated him. This was during my junior year in high school, when Great Expectations was one of three novels we were required to read for our Regents English class. (The other two were Jane Eyre and Lord of the Flies, both of which I loved.) True to my procrastinating tendencies, I put off reading Great Expectations until about two days before I was due to be take a test on it, when I panicked and sent my parents out to pick up a copy. I spent the next two nights trying to get through the book, whose long, leisurely sentences seemed to take me forever to plow through. Needless to say, my grade on that particular exam was not among my highest. In best teenage fashion, I blamed this on Dickens, specifically, his style. He was getting paid by the word, I said, and you could tell. A few years later, when I was an undergraduate, I gave Dickens another try, based on the recommendation of a professor whose opinion I esteemed highly. This time, it was Bleak House I struggled through for what seems to have been weeks, emerging from the book with my low opinion of Dickens substantially unchanged. You would think that would have been the end of my efforts with him, but when I was in my later twenties, I decided to give him another try. I was house sitting for a couple of weeks during the summer, and I brought a copy of Great Expectations with me. And finally, Dickens clicked for me. He more than clicked: the novel blew me away. Over the next decade, I made my way through several of Dickens’s other books: Bleak House (which I liked much more the second time around), Hard Times, Little Dorrit, and Dombey and Son among them. While I never stopped finding Dickens slow going, the rewards for that going increased dramatically, as I came to appreciate more what his style was doing, the way his figures transformed his characters and the settings through which they moved in fantastical ways—not to mention, his astonishing grasp of psychology, his endless fascination with the varieties of humanity. Although his novels aren’t quite Gothic in the way that his friend Wilkie Collins’s are, they’re certainly Gothic-inflected in their interest in the persistence of the past. I’m not sure how to chart Dickens’s influence on the horror literature that came after him. Certainly, it’s there in the fictions of a writer like M.R. James, and Kafka loved his work—which perhaps suggests how much there is in Dickens for a weird writer to respond to. More recently, both Stephen King and Peter Straub have referred to him. To speak for myself: as I moved further into writing my own fiction, Dickens came to seem more important to me. I suppose I saw him as a complement to Henry James; although there was something about Dickens, a certain flamboyance to his metaphors, a kind of generosity of spirit in his treatment of his characters, that seemed a bit more humane than James. As with James, for me, Dickens represented another alternative to minimalism.

At the emotional core of House of Windows are two (or perhaps three) powerful, and fatally fraught, relationships between fathers and sons. How much did your own experiences as both son and father inform the novel?

Oh man, that’s the mother lode, right there. I had a very complex relationship with my dad, who died when I was twenty-three. On the one hand, he was a great storyteller, and I think some measure of my own ability in this regard descends directly from his relating not only personal and family stories, but detailed summaries of movies he had seen and books he had read. On the other hand, he had a very forceful personality, and especially when I hit my teen years, I struggled with that. His death was unexpected and traumatic, and I suppose I’m still trying to come to terms with it.

In part, my experience as father to a pair of extraordinary sons has helped me to understand some of what passed between my dad and me. His anxieties about me—both the general fears that every parent has for a child and his specific concerns about me, about what I think he worried were some of my insane life choices—make much more sense now than they did when I was on the receiving end of them. But that father-son relationship is present, to varying degrees, in a majority of the fictions I’ve written.

Contrastingly, and apropos of your comment about Bloom’s anxiety of influence earlier, it seems to me that in many ways House of Windows is a novel about literary influence, and about how the stories of those who come before us can haunt, and even possess, our lives. It even struck me at one point that the novel could be read as a kind of literary exorcism, an attempt to conjure, or even abjure, the spirits of writers who left a deep impression on you. Do you think this is a fair reading, or did you feel, while you were writing the novel, that you were trying to do something of this sort?

It’s funny, I can remember the first time I heard Faulkner’s remark about the past not being past, it immediately struck me right to the core. For me, that emphasis on the persistence of the past is the through-line from the Gothic writers of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to Modernists like Faulkner and Woolf—and from them on to the horror writers of the later twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. It’s part of the reason I find Freud’s work, despite its abundance of problems, retains a certain blunt force: its recognition of the gravitational effect the past has on the present. Our lives are the results of all manner of stories, happening at all levels, feeding into the story we’re telling ourselves about ourselves. This remains one of the abiding virtues of horror fiction, its ability to recognize and wrestle with this state of affairs. Particularly when I’m writing at length, I find myself returning to these notions obsessively.

At the same time, as I guess my interest in literary influence makes clear, I think that literary works are constructed in an analogous fashion, in an over-determined way. This is very much so in House of Windows. The opening line is a rewriting of the first line of Henry James’s great story, “The Jolly Corner,” and the novel owes something to that piece, and to James in general. At the same time, the kind of explicit passions the book deals with would have been a bit much for James, which is where I suppose the example of Dickens assumes greater importance. In considering my use of those writers (and I’m sure of King and Straub as well) I’m not sure I’d use the word exorcism so much as exploration. It was more a case of discovering just how far these writers I loved could take me. In addition, in the course of writing the novel, I found other writers waiting in it whom I hadn’t anticipated, Shirley Jackson and Fritz Leiber in particular. (I think Edward Albee may be in the book, too, in some of the harsher exchanges between Roger and Ted, and also in the climax’s use of a kind of theater of the absurd-style staging.)

What’s interesting, as a kind of side note, is that when I look back on the novel now, from the distance of a few years, I see it as full of all manner of secondary narratives waiting to be expanded upon. From the life of Thomas Belvedere, my invented painter, to whatever happened in the Belvedere House during its time as a boarding house in the 1960’s, there’s a great deal more waiting to come out of the book.

As already mentioned, you are often associated with Lovecraftian horror, but in your notes to your Poe-themed (and perversely pedagogical) story “Technicolor” (among my favourites from The Wide, Carnivorous Sky, perhaps partially because of my own obsession with Poe, or my own professorial experiences) you write that, “it is with Poe that I have and feel the oldest, deepest connection.” Can you talk a little more about this felt connection, how it first emerged, how it has evolved over the course of your career, and how it plays out in your writing (critical, fictional, or both)?

I can still remember the first edition of Poe’s stories I had: it was called 18 Best Stories by Edgar Allan Poe, and boasted an introduction by Vincent Price (who was also credited as co-editor). I’m not sure when I purchased it; at a guess, I was probably in my early teens, and had already discovered Stephen King. I knew Poe’s work from before that, though. My seventh and eighth grade English teacher, Mrs. Lovelock—who was fearsome in the rules of grammar and in diagramming sentences—went a good way towards redeeming herself by reading “The Tell-Tale Heart” to our class for Halloween. I don’t remember being particularly frightened by the story, but I was impressed by Poe’s language. Possibly as a result of being raised Catholic, I was drawn to those writers whose language was more elaborate—more performative, you might say—a group that included Tolkien, Robert E. Howard in his more lyric mode, and Stan Lee when he was in full cosmic glory. Poe spoke to that in me. I read him in high school, then again, more intently, during my Honors English 2 class (with Bob Waugh) my freshman year of college. I think it was that Honors class that really opened me up to the depth of Poe’s achievement in stories such as “Ligeia” and “The Masque of the Red Death,” the combination of stylistic achievement, psychological insight, and dramatic intensity. Since then, I’ve returned to Poe’s work over and over again, sometimes to teach, others to respond to in my own writing. A couple of years ago, I picked up a three CD set of Vincent Price and Basil Rathbone reading some of Poe’s best stories, and when I’m on a long road trip to one convention or another, I try to listen to some of it. I think what continues to speak to me in Poe’s work is his insistence on pursuing his vision to whatever ends it takes him, as well as the way he situates what he’s doing within a larger literary context that expands to include Coleridge, the German Romantics, etc.

Speaking of the pedagogical connection, more than any other writer of fiction (and especially horror/weird fiction) I can think of, you often make tremendous and unsettling use of your experiences as an educator as the basis for your fictions. This is true not only in “Technicolor,” but also “Kids” (also from The Wide, Carnivorous Sky) and “Laocoon, or the Singularity” (from Mr. Gaunt). Beyond the old adage of “write what you know,” why do you think your experiences as a teacher have proven to be such fertile ground for you as a writer?

In part, I think this is due to the fact that all of my higher education has been conducted at public universities, at which I’ve encountered a tremendous variety of students and faculty. That might be enough of an answer, right there. However, SUNY New Paltz, the college at which I earned my BA and MA, and at which I’ve been an adjunct for a long, long time now, is also the center of the village of New Paltz. It’s the biggest source of revenue for the community, from the people it employs and from the money its students spend locally. It’s also the principle cultural center for the surrounding towns, staging plays, hosting art exhibits, putting on readings, etc. The point is, rather than standing apart from its surroundings (as the ivory tower of stereotype), the college is woven into the fabric of its community. In addition, a four year degree has become crucial to gaining decent employment in the current economy. All of this means that the university setting is relevant to a broader segment of the reading population than ever before. So it’s the kind of place where, as a writer, you can believably place a wide range of people in an equally wide range of situations. My use of the university also participates in the horror field’s ongoing obsession with places of learning, from Victor Frankenstein’s time at the University of Ingolstadt, to the scholarly haunts of M.R. James’s protagonists, to Lovecraft’s Arkham University. It’s a concern that mirrors the wider field’s ambivalence about knowledge: on the one hand, the university is the place where you can find all kinds of useful and necessary information about the supernatural menace you’re facing; on the other hand, said menace is likely to have been unleashed by someone messing around with old texts and/or conducting terrible experiments in that same spot.

Dennis, the sculptor-protagonist of your story “Laocoon, or the Singularity,” uses his young son as the model for his work. Knowing you are a devoted father who often writes about families (generally to whom terrible things happen) I can’t help but see a biographical parallel here. How extensively would you say you draw on your own family life for fictional inspiration? Has this ever led to any concerns?

While I’ve included my immediate family as characters in some of my work, I’ve tried to maintain what I hope is a healthy space between our life and what happens in my fiction. I do believe that the art you make is crafted from the materials of your life, but I prefer the idea of inventing from what you know as opposed to reproducing what you know. It’s been my experience that details from my life emerge in what I’m writing regardless of whether I’m conscious of them or not. That said, over the past couple of years, I experimented with writing a number of stories that were much more directly rooted in autobiographical materials. Even in that case, though, the resulting stories tended to diverge in significant ways from the material that inspired them. Now, I’m trying to do exactly the opposite, to write stories that have no direct relation to my life; I’m sure I’ll discover all sorts of hidden connections to my life in them.

It’s funny: a few years ago, I was on a panel at ReaderCon on exactly this topic. A couple of the panelists were quite regretful of the use they had made of their family members in past works. From the conversation, though, it seemed clear to me that what bothered them was that they had included their family members in their fiction in order to settle scores with them. If you’re going to do this, then I think it’s much more likely that you’re going to regret it at some point in the future. If you’re including family members because that’s what your story needs, then I think you’re much more likely to do so to better effect.

Your novelette, “Shadow and Thirst” is included in the recent anthology of vampire fiction, Seize the Night, edited by Christopher Golden. What can you tell us about the story, and about the anthology generally?

Chris Golden’s invitation to the anthology stated that he was looking for frightening vampire stories. No sympathetic vampires—and certainly, no romantic vampires—need apply. So anyone picking up the book should be aware that its vampires are not a sympathetic bunch. As for my story, it began with the image of a short tower at the foot of the hill in my backyard. I’ve spent a lot of time in recent years re-reading Robert Browning’s “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came” as part of a would-be dissertation on the poem’s relationship to Lovecraft’s fiction. The tower I visualized was this structure, the “round squat turret” Browning describes. I had the idea that it might appear and then disappear. At first, I thought about making the tower itself the vampire, but this seemed a bit too passive, so I decided that the tower would be connected to the vampire it was imprisoning. Of course, Stephen King has made extensive use of Browning’s poem in his Dark Tower series of novels and stories, which, to tell the truth, intimidated me a little. But I decided that the best thing to do was to embrace the poem and see what happened. At the time, my older son was a police officer in the city of Baltimore. He had relayed to me a number of anecdotes that seemed as if they might be part of the developing narrative (albeit, with the serial numbers filed off, so to speak); in fact, there wound up being quite a bit more of our shared history in the story than I had anticipated. As the story progressed, I realized that its vampire was connected to figures mentioned in my second novel, The Fisherman. The piece turned out to be packed full of things, some of which I didn’t pick up on, myself, until well after it was done (e.g. the parallel between the police officer son and the police officer vampire).

In a recent PstD interview, talking about his in-progress trilogy of vampire novels (Motherless Child and its sequels), Glen Hirshberg professed to be surprised to find himself writing vampire fiction, citing a lack of interest in most of what has been done with the vampire in recent popular culture. Do you feel similarly? What are some of the literary and/or cinematic treatments of vampirism that have made the greatest impression on you?

I love vampires. One of the first stories that scared me while I was reading it was a vampire story, Robert E. Howard’s “The Horror from the Mound.” The first time I read it, Stephen King’s ‘Salem’s Lot bowled me over, as did his short stories “One for the Road” and “The Night Flyer.” I loved John Skipp and Craig Spector’s The Light at the End. I was impressed by Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire, and enjoyed the hell out of The Vampire Lestat. I was completely absorbed by Elizabeth Kostova’s The Historian. I loved both of Glen Hirshberg’s vampire novels. Laird Barron’s “The Siphon” is a great story, as is Nathan Ballingrud’s “Sunbleached.” There are more great vampire movies than I can remember here: the original Nosferatu, Martin, the 1985 Fright Night, The Lost Boys, Near Dark, Habit, From Dusk till Dawn, Let the Right One In, Thirst, Byzantium, Only Lovers Left Alive, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night among them. And let’s not forget Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and Angel, and on the comic book side of things, Tomb of Dracula and 30 Days of Night. A few years ago, Paul Tremblay told me that I had to write a vampire novel; when I asked him why he said that, he explained that it was because I was always telling him this was what he had to do, which he took as a sign of my deep interest in the project. The moment he said this, I realized he was right. It’ll take me while to get to, but in the meantime, I’m sure I’ll be returning to the figure in shorter works.

You’ve commented in a blog post about “Shadow and Thirst” that it is best read alongside Laird Barron’s contribution to the same anthology. Can you give us a taste of how these stories are connected?

Without wanting to give too much away, I can tell you that there’s an important name that appears in both stories. I can also tell you that, if you pay attention to my story, you’ll find it’s picked up a passenger from Laird’s.

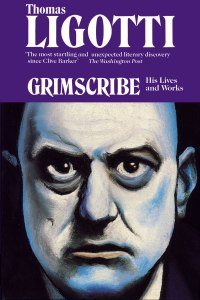

Upon reading your story in The Grimscribe’s Puppets, “Into the Darkness, Fearlessly,” I was struck by the close connection between it and Barron’s story “More Dark” from his collection The Beautiful Thing that Awaits Us All. Can you talk a little about the connection between these stories, and the relationship they both have to the work of Thomas Ligotti? About how these story-pairing collaborations between you and Barron evolve?

Laird and I chat all the time, via phone and in person. We’ll kick around story ideas, discuss things we’re working on, talk out challenges in our latest stories. He told me about “More Dark” as he was writing it; I was particularly struck by the detail of the horror writer whose head is found in the freezer of another writer he had tormented, and thought it would be interesting to flesh out that detail in a work of my own. Around the same time, Joe Pulver asked me to contribute to an anthology he was putting together of fiction inspired by the work of Thomas Ligotti. Given where the story was headed, I thought that it might fit into such a project in an interesting way. Ultimately, I think our two stories are different in their approach to Ligotti and his work. “More Dark” makes of him a kind of fearsome embodiment of all the darkness at the center of his work, while my story plays more with Ligotti’s themes, especially his concern with the way in which a character might be absorbed into a sinister conceptual system.

I understand you are close to publishing a third collection of short fiction, and your second novel, The Fisherman, has just been released. Can you give us a foretaste of these projects?

My second novel, The Fisherman, was released from Word Horde press in early summer of 2016. It tells the story of a pair of widowers who take a fishing trip to a stream which is reputed to allow contact with the dead. Along the way, the men learn the story of the stream’s origin, which connects to the construction of the Ashokan reservoir in the Catskill Mountains, and a monstrous evil the workers building the reservoir encountered.

Later in 2016—probably around Halloween, I think—my third collection of stories, Sefira and Other Betrayals, will be published by Hippocampus Press. It will bring together half a dozen previously-published stories: “In Paris, In the Mouth of Kronos,” “The Third Always Beside You,” “The Unbearable Proximity of Mr. Dunn’s Balloons,” “Bloom,” “Renfrew’s Course,” “Bor Urus,” and a new novella, “Sefira.” Oh, and story notes, too. Paul Tremblay has kindly agreed to write the introduction for the book.

Like James’s Turn of the Screw, Lovecraft’s “Call of Cthulhu,” and your earlier novel House of Windows, The Fisherman features a nested narrative structure, a story within a story. Why is this mediated structure so central to the history of modern horror fiction, and why did you decide to adopt it in both cases?

To a certain extent, I think you can trace the nested structure’s early examples—say, Frankenstein—to the narrative conventions of the age in which they were composed. Read a lot of late-eighteenth/early-nineteenth century novels, and you’ll find that they’re full of narratives tucked one inside the other, often contained within the letters the characters are writing back and forth. In the case of the Gothic novel, I have to confess, I wonder if the structure doesn’t in some way encode the opposing ideologies of its later-eighteenth century invention. What I mean is, on the one hand, there’s a great faith in reason; on the other, there’s an anxiety that the irrational (in the form of the supernatural, in particular, but also, I think, insanity) might be a stronger force. The mediated structure of the Gothic novel allows you to indulge both these points of view: you can have a story of the irrational contained within/counterpoised with a narrative that accounts for it rationally. I would guess that the continued use of the nested structure owes itself in part to simple imitation of these earlier narratives.

Questions of literary history aside, I think that the nested narrative allows for intriguing rhetorical effects. There’s a gap, after all, between the stories, and in order for that gap to be bridged, the reader must of necessity be involved in the process. There’s a way in which the connection-making reminds me of the leap that’s involved in a metaphor, of the flare of insight that results. Of course, when you have a text that contains a number of different nested narratives, you can wind up with an effect that’s more akin to transumption, the troping of a trope, which leads in all kinds of interesting directions.

The Fisherman is a richly intertextual novel, and invokes, in some cases explicitly, a wide range of literary influences, including many of those writers we’ve already discussed. Two earlier works that it foregrounds in particular, though, are King’s novel Pet Sematary and Melville’s Moby Dick. While they may seem like an unlikely pairing, The Fisherman forcibly hooks these very different literary leviathans together. Can you tell us about why these novels are particularly important for you personally, how you see them as being connected, and how they feed into the cold, deep stream of melancholy and terror that is The Fisherman?

What’s fascinating about this question is, The Fisherman’s use of Moby Dick was absolutely intentional, and was in keeping with my creative practice when I started it, which involved riffing on classic works of American literature. However, until I read your question, it never occurred to me once that Pet Sematary might be a part of the novel, too. And yet it is, it so totally and completely is. I remember when Pet Sematary was announced as the novel that Stephen King had thought too much—too bleak, too unrelenting—to publish. Of course, this made me want to read it immediately. Without really intending to, it’s the novel of his that I’ve come back to most frequently over the years. When I was in high school, I performed Jud Crandall’s story about the return of Timmy Baterman as a kind of dramatic monologue for the drama club. Over the years, I’ve taught the book a number of times. I agree with Ramsey Campbell that it’s one of King’s most daring, most heartfelt, and revelatory works. It’s a narrative that slices right down to the bone, to the terrible realities of suffering and death. It’s also a book that seems rooted in the literary soil of New England; there’s a lot of Hawthorne in there. What I think it has in common with Moby Dick is its portrayal of men driven to monstrous extremes by the awful situations into which they’re plunged. Both Ahab and Louis Creed come face to face with Melville’s famous pasteboard mask, the guise that existence wears, and both desire to punch through it, to find out what’s on the other side of it, no matter how terrible.

It’s funny: some years ago, I was on a long car trip with my older son, and the conversation turned to Stephen King’s works. He asked me about Pet Sematary (I’m not sure why; maybe something to do with the movie) and I wound up telling him the story of the novel as we drive south through New Jersey. At the end of my re-telling, when Louis’s shoulder is grasped by the hand of the dead, I grabbed my son’s knee, and I swear to God, he practically leapt out of the car. I suppose I took that as proof of the power of King’s novel.

And finally, in your notes to the novel, you mention that The Fisherman was partially informed by your son’s penchant for game fishing. Since The Fisherman features some pretty freaky fish (or are they?), what is the strangest thing your son has ever hooked?

A brief consultation with my son has revealed that, as far as he’s concerned, his strangest catch was a snapping turtle that took his lure in its jaws and did not release it until he reeled it into view; whereupon, it swam off. Speaking for myself, the eel he caught once was pretty freaky, and the mouth of the walleye he hooked was full of surprisingly sharp teeth.

***

John Langan is the author of two novels, The Fisherman (Word Horde 2016) and House of Windows (Night Shade 2009), and two collections,The Wide, Carnivorous Sky and Other Monstrous Geographies (Hippocampus 2013) and Mr. Gaunt and Other Uneasy Encounters (Prime 2008). With Paul Tremblay, he has co-edited Creatures: Thirty Years of Monsters (Prime 2011). He is one of the founders of the Shirley Jackson Awards, for which he served as a juror for their first three years. Forthcoming in later 2016 is his third collection, Sefira and Other Betrayals (Hippocampus). Currently, he is reviewing horror and dark fiction for Locus magazine. He lives in upstate New York with his wife, younger son, and he can’t remember how many animals.