By Sean Moreland

This informal and image-driven essay is loosely based on two closely related conference papers. The first was given as part of the academic track of NecronomiCon, in Providence, RI, August 2017. The second was delivered as part of the Visual & Performing Arts & Audiences Division at the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts in March, 2018. I further develop my analysis of the relationship between Lovecraft’s “cosmic horror” and the aesthetics of the sublime in the essay “The Birth of Cosmic Horror from the S(ub)lime of Lucretius,” in New Directions in Supernatural Horror Literature. My analysis of the significance of spiral motifs in Lovecraft, and especially in his writings up to 1927, is developed in the article “Stages of The Spiral: Lovecraft’s Descent into the Maelstrom,” which will appear in the collection Lovecraftian Proceedings Volume 3, forthcoming summer 2019 from Hippocampus Press. Eventually, these ideas will be more fully developed as a chapter in my book-in-progress, Repulsive Influences: A Historical Poetics of Atomic Horror.

***

Asked in an interview about the influences on his magnum opus of comic-cosmic horror, Uzumaki, renowned mangaka Junji Ito replied that the “different stages of the spiral” visualized by the book “were definitely inspired from the mysterious novels of H.P. Lovecraft.”

As Ito’s remark suggests, Uzumaki responds to and adapts Lovecraft’s spirals as figurations of cosmic horror, figurations profoundly influenced by Lovecraft’s own historical, cultural, and scientific context.

HPL ala Ito

In Lovecraft’s writings, spirals initially figure visible cosmic order and scientific discovery, as suggested by his excited responses to early photographic images of the spiral nebula. In 1917, Lovecraft wrote:

“A recent discovery of immense importance to our knowledge of the structure of the universe is that of the incredibly rapid rotation of certain large spiral nebulae… how rudimentary is our present information regarding the larger outlines of the visible creation wherein we dwell.”

G.W. Ritchey’s 1910 photoplate of the M51 spiral nebula

In Lovecraft’s writings as of 1918, however, beginning with “The Poe-et’s Nightmare,” spirals increasingly come to figure disorder and chaos, an association intensified by Lovecraft’s gradual acceptance of the cosmic consequences of the second law of thermodynamics, contemporaneously with what he called the “maelstrom” of the First World War’s chaotic violence. As Lovecraft puts it in a 1923 letter to Frank Belknap Long:

“In art there is no use in heeding the chaos of the universe. I can conceive of no true image of the pattern of life and cosmic force, unless it be a jumble of mean dots arrang’d in directionless spirals.” It is a remark Lovecraft makes by way of criticizing the “chaotic” work created by Modernist and surrealist writers and artists, which (futilely, to his mind) attempts to reflect the (dis)order of existence by eschewing traditional formal structures.

1923 spiral photograph by Man Ray

Without explicitly referring to Lovecraft, Uzumaki provides a powerful realization of how spirals in his writing figure at once an ordered, mechanistic and predictably determinate universe, and a chaotic and unknowable one. I take Ito’s acknowledgement of Lovecraft’s influence as a license to frame Uzumaki (perhaps perversely) in terms of the context of Lovecraft’s work, although this necessarily means tearing it from the context of Japanese cultural, narrative and visual traditions in the late 20th century. Largely excluded from my discussion, for example, are Uzumaki’s connections to Ero-Guro-Nansensu, the spiral patterns of Hokusai’s ukiyo-e, Ito’s parodying of conventions of popular romance manga, or his homages to fellow horror mangaka Kazuo Umezu.

Katsushika Hokusai’s ukiyo-e often feature spiral motifs, including many of his “laughing demon” images and the better-known Great Wave off Kanagawa.

Similarly, I don’t explore the topic of Lovecraft’s wider cultural reception in Japan. Readers interested in this topic should see Hisadome Kenji, “The Cthulhu Mythos in Japan,” trans. Edward Lipsett, Night Voices, Night Journeys Volume One: Lairs of the Hidden Gods, edited by Asamatsu Ken (Fukuoka: Kurodahan, 2005), 339-352,. Those interested in HPL’s pervasive influence in manga and anime could start with Jason Thompson’s NSFW piece here.

Unlike artists Osamu Tezuka, Richard Corben, John Coulthard, or Ian Culbard, Ito has never produced a literal adaptation of Lovecraft’s stories. Unlike Alan Moore, he is not known for his re-imaginings of Lovecraft’s characters or plots; nevertheless, Ito is among the most important visual interpreters of Lovecraftian cosmic horror, and Uzumaki is his greatest expression of it to date. Ito is open about Lovecraft’s influence; he remarks, with apposite vagueness, that Lovecraft’s “expressionism with regard to atmosphere greatly inspires my creative impulse.” Ito’s characterization of Lovecraft echoes Lovecraft’s own definition of weird fiction in Supernatural Horror in Literature, which emphasizes “A certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces,” and “a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.”

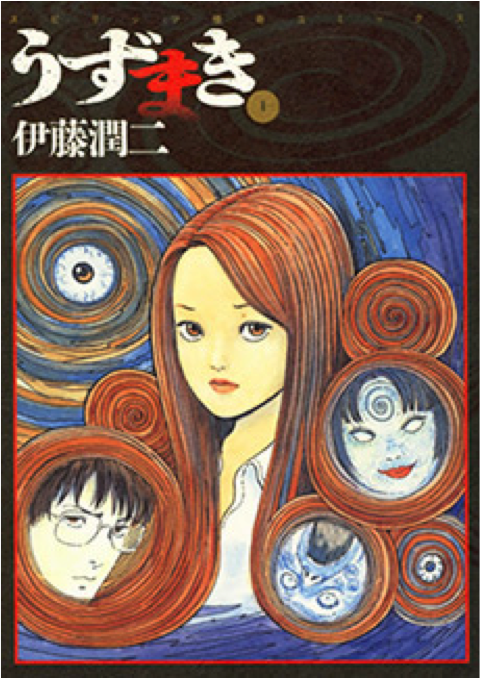

Uzumaki provides such a suspension by visualizing the gradual speiromorphosis of a coastal Japanese town, portraying an ensemble cast of ill-fated characters while often focusing on the futile escape attempts of two students, Kirie Goshima and Shuichi Saito. Uzumaki offers a few implicit homages to Lovecraft’s stories, particularly with the chapter “The Medusa,” reminiscent of Lovecraft’s collaboration, “Medusa’s Coil” (minus the viciously racializing subtext.)

Junj Ito, Uzumaki, trans. Yuji Oniki (San Francisco: VIZ Media, 2010)

However, Ito’s interest in the epistemological and aesthetic roots of Lovecraft’s spiral obsession is most evident in the “lost” chapter of Uzumaki, making it an effective bridge between the early 20th century astronomical context of Lovecraft’s cosmic horror and the turbulent transfigurations of Uzumaki as a whole.

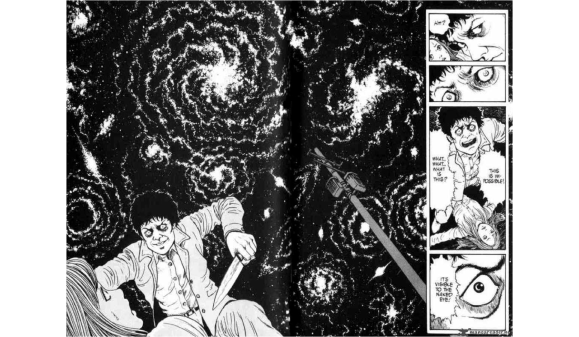

Called “Galaxies,” this chapter is disconnected from the rest of the arc, appearing in the VIZ omnibus edition as a sort of postscript. “Galaxies” introduces the spiral as an alien astronomical phenomenon.

Junj Ito, Uzumaki, trans. Yuji Oniki (San Francisco: VIZ Media, 2010)

It begins with Shuichi telling Kirie that he has discovered a galaxy that “isn’t listed in any book,” insisting she look through his telescope to see for herself. Kirie is the visual focus of the opening panels; the reader looks at her. With the fourth panel, we see the spiral phenomenon for the first time through her eyes, a traditional suturing technique in both comics and film.

We see the human locus of our identification, then we see the supernatural threat through their eyes, then we see their reaction to it, and so on. Inside the panel’s square borders is a circular secondary border representing the telescopic lens. Inside that, a twisting spiral stellar formation, strongly reminiscent of early photographs of the spiral nebulae.

The next page shifts scenes and elides time, showing Kirie at school, telling her science teacher about the discovery. While skeptical, he agrees to ask his friend, “an armchair astronomer” to verify Shuichi’s find. Another turn of the page brings the reader to that night, and the home of Torino, struck with manic elation when he sees the spiral galaxy for himself (617). The discovery leads to “a sudden astronomy boom” in Kirie’s school, the “new” galaxy becoming an object of community-wide obsession. This obsession is especially powerful for Shuichi and Torino, who both experience “radio waves” emanating from “some entity” in the spiral galaxy, an echo of the interstellar telepathic communication practiced by many of Lovecraft’s alien entities.

Shuichi is desperate to escape this nefarious astral influence, while Torino wants to use it to glorify himself. He tells Shuichi that he must kill him, in order to get credit for the discovery. Eventually, more new galaxies are discovered, emerging as if in correspondence with the individual subjectivities of the town’s residents, beckoning each of them to their own particular sidereal dissolution, a conceit closely related to that at the heart of Ito’s manga, The Enigma of Amigara Fault. Delirium and violence ensue, culminating in Torino’s attempts to kill Kirie, who objects to his taking credit for Shuichi’s discovery:

As he overpowers her, the sky behind him erupts into a swirling mass of stellar spirals. Kirie is spared as Torino shouts up to the swirling mass of stars, demanding they acknowledge him as their discoverer; he is then swept up in a cosmic whirlwind, his head twisting into a nested series of spirals, until it explodes outwards and up, turning into a small galaxy and surging up to the heavens. “Galaxies” is a grotesque mockery of the anthropocentric hubris of the romantic sublime, in which the object is observed, absorbed, and used to stabilize and elevate human subjectivity. Instead of this stabilization, Torino is translated into an astronomical object himself, displaying what Vivian Ralickas, with reference to Lovecraft’s stories, calls an “inherent, anti-humanist critique of sublimity.” Ito follows Lovecraft in revealing the pseudo-apotheosis of religious and romantic sublimes to be ridiculous, while expressing this absurdity in images that are themselves sublime; stellar nebulae, hurricanes, whirlpools, cyclopean subterranean structures.

Uzumaki proper opens very differently, with an establishing full-bleed splash: Kirie stands atop a hill, her back to the reader, looking out over the town and toward a misty grey sea, distant black lighthouse and scuttling clouds.

Junj Ito, Uzumaki, trans. Yuji Oniki (San Francisco: VIZ Media, 2010)

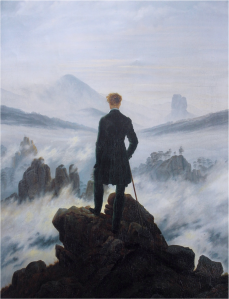

This composition is in many ways a traditional Rückenfigur, echoing a painting long associated with Romantic sublimity, Kaspar David Friedrich’s “Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog” (1818).

Kaspar David Friedrich’s “Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog” (1818).

Friedrich’s painting puts viewers in the position of witnessing the encounter between human subject and sublime landscape, inviting them to revel in this figure’s mastery of nature. The Wanderer’s position conceals his face, universalizing the encounter between spectator and spectacle while inviting disinterested reflection by preventing the emotional contagion of a facial close-up. An elevated, masculine figure, Friedrich’s Wanderer is an emblem for the mastery of nature by a transcendental aspect of human subjectivity, whether it is understood to be sensibility (as in Ann Radcliffe’s novels) or moral reason and a sensus communis (as in the Kantian version of the sublime encounter.)

The Wanderer’s placement is paralleled by Kirie’s, but with a number of significant differences. Where the Wanderer’s stance bespeaks strength and mastery, his arms cocked confidently as he leans on his cane, Kirie’s bespeaks apprehension and vulnerability. One hand clenches the handle of a schoolbag, its pinkish colour linking it to the roofs of the tidy houses below; her feet, close together, point directly toward the gathering storm visible on the horizon, the line of her narrow shadow stretching behind her, suggesting her inexorable movement toward it. Subtly, this signals the agency of the spiral itself, an agency to which Kirie and the other human characters can only passively respond. Kirie’s other hand hangs half-curled at her side in a nervous clench, index finger slightly open, as though she is about to point the storm out to the viewer who lurks, unseen, behind her. Where the Wanderer surmounts his environment and is fully centred, Kirie is offset. Despite her elevated vantage above the town and sea, she is askew, displaced. Where the Wanderer seems implacable, Kirie is buffeted by unseen powers.

The horizon, fog and wind in Friedrich’s painting are soft, nebulous, edgeless in contrast to the Wanderer, who is as solid as the indomitable rocky promontory on which he stands; contrastively, the dark density of the lighthouse in Ito’s image draws both Kirie and the reader’s eyes, underlining the stormy sky’s surge of black lines. In three places, these lines converge into whirlwinds. These whorls are echoed by a series of tiny spiralling plants emerging from the clutch of wild grasses visible between Kirie and the town. These green fuses appear innocuous here, but their presence on this page crucially distinguishes its introduction of speiromorphism from that in “Galaxies” by portraying it not as an extra-planetary, alien force, but as an elemental principle, already diffusely present in the earth and its diverse life.

Junj Ito, Uzumaki, trans. Yuji Oniki (San Francisco: VIZ Media, 2010)

When readers turn to the second page, the small spirals on the opening splash are supplanted by a single, brush-stroked, vaporous spiral, extending to the edges of the full-bleed two-page spread that follows. Kirie’s apprehensive face stares off the facing page, where presumably the clouds still swirl ominously. Opposite her, beneath the line of her gaze, past the grass, more of which now coils, the town sprawls. Friedrich created space for disinterested contemplation by putting the Wanderer between viewer and landscape and excluding his face from the image. While this effect is echoed by Uzumaki’s opening page, it is shattered here, as the reader comes face-to-face with Kirie’s wide-eyed visage. It is a jarring transition, especially because the swerve of perspective that produces it means readers have executed a spiral in relation to Kirie’s position, curving ahead of and moving menacingly toward her.

From its outset, Uzumaki uses its visual style and structure to aggressively undermine the privileging of the human figure in images informed by Romantic capitulations of the sublime encounter. It also subtly sutures the reader’s perspective, but not to Kirie (as the more traditionally structured “Galaxies” does). In these opening pages, we are invited to watch Kirie, rather than identify with her, while our perspective is sutured instead to the invasive swerves of the spiral. Thus Ito visually realizes Lovecraft’s dictum that the “true ‘hero’” in weird fiction is a “set of phenomena”:

“Individuals and their fortunes within natural law move me very little. They are all momentary trifles bound from a common nothingness toward another common nothingness. Only the cosmic framework itself—or such individuals as symbolize principles (or defiances of principles) of the cosmic framework—can gain a deep grip on my imagination and set it to work creating. In other words, the only “heroes” I can write about are phenomena.”

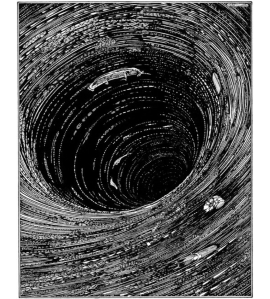

While its presentation varies widely from episode to episode, the phenomenon at Uzumaki’s core is, effectively, the idea that under a certain set of unexplained conditions, at certain times, every object and entity in the vicinity of Kurozo-Cho becomes subject to a perverse version of fluid mechanics, spontaneously beginning a gradual transition from a laminar to a turbulent flow regime, assuming the form of a vortex or eddying whirl. This transition is signalled by Ito’s visual references to Harry Clarke’s illustration of Poe’s “A Descent into the Maelstrom”:

Clarke’s 1919 illustration for Poe’s tale

Poe’s description of the marine vortex in “Maelstrom,” deeply influenced by his interest in 19th century mathematics and astronomy, has been held up by some physicists as uncannily anticipating contemporary research into the dynamics of marine and astronomical vortices, leading some contemporary physicists to use it as verbal demonstration of the mechanics of a Lagrangian vortex, arguing that it “resonates with our intuition for black holes in cosmology.”

The whirled horizon on Uzumaki’s opening page also suggests a second visual parallel, this time to Van Gogh’s “Starry Night.” This parallel becomes more evident as Uzumaki unfolds.

Vincent Van Gogh, “The Starry Night,” 1889.

In Uzumaki’s opening splash, the too-close vertical shape of the poplar trees in “Starry Night” is paralleled by Kirie’s figure, and where the emerging spire of a church punctures Van Gogh’s town, it is the distant, but darkly prominent, image of the lighthouse that punctures Ito’s.

Later in Uzumaki, the lighthouse assumes the position of Van Gogh’s poplars, uncannily underlining the unruly animation of an architectural object that is itself subject to seemingly undirected, turbulent transformation. Ito and Lovecraft’s shared fascination for vortices also accounts for Uzumaki’s many visual allusions to Van Gogh’s paintings, which have fascinated modern physicists by their detailed visual representations of turbulent flow.

Junj Ito, Uzumaki, trans. Yuji Oniki (San Francisco: VIZ Media, 2010) a caption

Ito excels at creating awe-inspiring and horrifying effects through his curvilinear visual designs and narrative structure. His detailed, dynamic depictions of turbulent matter lend a realism to Uzumaki that make a suspension of disbelief possible even during its most outré episodes. His line-work serves a purpose similar to the gradual accumulation of physical detail that shores up Lovecraft’s greatest works of mature cosmic horror, “At the Mountains of Madness,” The Colour out of Space,” and “The Shadow Out of Time.”

Ito’s vortical techniques create unforgettably inventive grotesques. Their cumulative effect is a distortion, and eventually an erasure, of the human figure, one first made explicit by the fate of Shuichi’s father:

You and me…. or proto-maki? Junj Ito, Uzumaki, trans. Yuji Oniki (San Francisco: VIZ Media, 2010)

Uzumaki‘s third chapter introduces Azami, a new student at Kirie’s school. A visual echo of Ito’s earlier manga character Tomie, Azami has a small crescent-shaped scar on her forehead, which she claims typically makes her irresistibly attractive. Under Uzumaki’s turbulent regime, however, the scar rapidly transmutes from a charming crescent into a spiral, continually increasing its dimensions by drawing more and more material into its involutions, absorbing first the majority of Azami’s face, and then objects and characters in her vicinity.

During this episode, a series of panels focused on Azami’s face forces readers to follow the course her eye takes as it spirals into the vortex most of her visage has become, finally receding into the depths of the panel and disappearing. By forcing readers to follow Azami’s displaced eye down a vortex into subliminal oblivion, this page provides a disturbing metonymy of Uzumaki’s suturing of the reader’s gaze to spirality itself:

Junj Ito, Uzumaki, trans. Yuji Oniki (San Francisco: VIZ Media, 2010)

Uzumaki uses its weird regime of turbulent flow to birth numerous grotesques, torquing human forms over and over again into spiral mutations in a relentless visual erasure of the anthropic that is, arguably at least, more “Lovecraftian” than anything Uncle Theobald himself ever wrote.

The manga is at its most Lovecraftian during Kirie and Shuichi’s descent into the subterranean mega-spiral structures that turn below the transfigured town. This brief procession of panels in particular echoes the “palaeogean megalopolis” discovered by Danforth, Dyer and co. in At the Mountains of Madness.

Junj Ito, Uzumaki, trans. Yuji Oniki (San Francisco: VIZ Media, 2010)

Appropriately enough, it is in Mountains that the tension between the spiral as chaotic emblem of undirected mutation and the spiral as emblem of harmonious order becomes most evident. Here, the admirable (for HPL, in any case) civilization of the Elder Things is embodied in their architectural art, oriented around a “spiral band of heroic proportions,” while the revolting, destructive power of the shoggoth is likewise figured by the spiral waves of force that surge before its protoplasmic bulk.

Ultimately, however, Ito draws his readers into cosmic horror with a rather unLovecraftian comical twist. Much as “Galaxies” humorously subverts the lofty aspirations of the cosmic sublime, Uzumaki romantically subverts Lovecraft’s grimdarkest reaches with a dark grin.

Its final, and strangely sweet, visualization of speiranthropy occurs with the culmination of Kirie and Shuichi’s star-crossed romance. The beset teens finally share an embrace that leads to their coiling around one another in a serpentine double-helical structure. In these panels, speiranthrôpos marries the microcosmic spirals of DNA to the macrocosmic mega-spiral that absorbs the entire town into its unity on the pages that follow.

This is the last glimpse Uzumaki offers readers of an anthropic form. The remaining panels provide interior images of the mega-spiral’s self-completion as vast, conjoined symmetrical speiromorphs interlink and twist. The panel borders fragment these massive forms, a Piranesian effect that amplifies their alien majesty. The relationship between panel-to-panel movement and narrative time is ambiguated; there is no narration, the images overlaid instead by sibilant, inhuman onomatopoeia that intersects the images it overlays in a disorienting, and literally posthuman, montage.

Until the reader turns to the last page, that is… But that’s another conversation.