By Sean Moreland, PhD

This is the text of a conference paper I delivered as part of the inaugural Society for the Study of the American Gothic (SSAG) conference in Salem, Ma. in March 2024, as part of a panel focused on Poe and Lovecraft.

It represents the conjunction of my interest in the literary and cultural contexts of various forms of modern religious Satanism, Romantic literary Satanism, the history of “Satanic Panic” narratives, and, of course, Edgar Poe’s writings and cultural legacy in general.

In part, the paper stemmed from my interest in how the (chiefly British, German and later French) writers associated with early nineteenth-century Romantic Satanism were transmitted into the peculiarly American emergence of explicitly Satanic discourse and soi-disant Satanic organizations in the 20th century, and my realization that Poe is a crucial, but unrecognized, conduit for this transmission.

While I’ll eventually return to and develop it more fully (and it will likely end up breaking into a couple of longer pieces, as many of my conference papers tend to do; one will focus in more detail on the concept of, to echo the title of M. David Litwa’s fascinating recent study, the Gnostic concept of The Evil Creator in Poe’s work, Romantic Satanism, and American Transcendentalism more broadly; another will focus on the transformative reception of Poe’s work by Paschal Beverly Randolph and later esotericists) I thought I’d share the original conference version here, short and sketchy as it is. I haven’t included endnote citations in this version of the text but have supplied links to many of the referenced texts.

“I lost a limb / on the left hand path / and I never, ever, ever / got it back”

Cold Cave, “A Little Death to Laugh”

Introduction: Poe and Satanic Discourse

This paper situates Poe’s writing in the nineteenth-century discourse of Romantic Satanism while illuminating its pervasive, but critically under-recognized, influence on various forms of modern religious Satanism. In Jesper A. Petersen’s words, “the nature of modern Satanism is delineated through a distinction between discourse on the satanic and satanic discourse,” “the difference between cultural stereotypes and self-ascribed satanic identities.”

In terms of the “discourse on the satanic,” Poe’s writings and literary persona were yoked to popular conceptions of the demonic, a process accelerated by his literary executor and first biographer, American writer, editor, and one-time Baptist minister, Rufus W. Griswold, whose characterizations were amplified in turn by later writers, including Baudelaire in France and Swinburne in England, who saw in Poe’s persona their own ideals of the “poete Maudite,” hurling daemonic maledictions at a tyrannical divinity and perverse universe. My primary interest here is rather Poe’s relationship with “satanic discourse,” the “positive self”-identification shared by various forms of modern Satanism. For, while Poe did not explicitly identify as a Satanist, his writings have shaped the forms of religious self-identity of those who, since the late 19th century, have so identified.

The Crimson Ribbon: Esoteric and Rationalist Satanism

Modern Satanists exist on a spectrum. Imagine it as a crimson ribbon, hung between two horns on a goat’s skull, mounted above a gaudy altar. The first horn is “esoteric”–those who follow what is often referred to, using terminology introduced by the co-founder of Theosophy H. P. Blavatsky, as the “Left Hand Path” (originally her translation of the Sanskrit tantric term vamachara). The second is “rational” —those whose adversarial attitude toward supernatural, theistic religion is informed by a physicalist, atheistic worldview.

For example, the “rationalist” Satanism of the Church of Satan, which holds Anton LaVey’s Satanic Bible (1969) as a definitive text, falls closer to the second horn. Yet LaVey’s teachings foreground a form of magical practice based on the ritualistic amplification of one’s “Will,” a concept deriving directly from the magical philosophy of the early 20th century occultist Aleister Crowley, and indirectly (as we shall see) from Poe’s writings. Even closer to the “rational” horn is the Satanic Temple, or the unaffiliated but ideologically similar Global Order of Satan. Both groups emphasize secularism, religious pluralism, individual autonomy and reproductive rights, and the psychological and social importance of ritual rather than magical practice. In contrast, The Temple of Set, whose founder Michael Aquino split off from the Church of Satan in 1975, falls much closer to the first horn, advocating the use of “Black Magic” to ultimately attain power over reality and personal immortality.

Poe’s work runs the full length of this crimson ribbon. On one hand, it is saturated in esoteric ideas, as Barton Levi St. Armand long ago emphasized: “Poe’s metaphysic derives …from those …unorthodox and even heretical doctrines…current at the beginnings of Christianity itself and then suppressed or driven underground by the actions of… dogmatic Church councils.” Serving as a vehicle for these doctrines, it has influenced the course of Western esotericism since the mid-19th century. On the other, Poe’s work is profoundly shaped by Epicurean philosophy, suffused by a poetics of perishability, and frequently satirizes what Lucretius called religio, which I take to mean those forms of religion that reinforce hegemonic state and social power and prescriptive morality through promises of personal immortality and divine reward or punishment.

Poe’s Romantic Satanism: Farcical Fausts

Understanding Poe’s place in the contemporary Satanic milieu requires understanding how contrastive Gnostic and Epicurean influences shape his version of Romantic Satanism, influences evident in his writings as of the early 1830s, when Poe develops two narrative structures that reflect them. The first and most obvious is the farcical Faustian tale, which Poe deploys first in 1831 with early drafts of “The Bargain Lost,” published after extensive revision as “Bon-Bon” in 1835, and last with “Never Bet the Devil Your Head” in 1841. The second features a male, first person, unreliable narrator who is obsessed with the death and apparent resurrection of a beloved woman. Poe initially develops this structure with “Berenice” but it recurs throughout many of his later poems and tales, from “Morella” and “Ligeia” to “The Raven.”

“Bon-Bon’s” Devil is explicitly linked to Epicurean philosophy – the Devil insists “I am Epicurus!” – while caricaturing what Peter Schock calls the “daemonic sublimity” of Milton’s Satan. It is the tale’s eponymous gourmand-philosopher that seems to embody the egotistical sublime associated with this figure; it is “impossible to behold the rotundity of his stomach without a sense of magnificence nearly bordering on the sublime,” “in its immensity a fitting habitation for his immortal soul.” In contrast, the tale’s devil is marked by his contemplative air and “a pair of green spectacles,” giving the impression “of an ecclesiastic.” Self-identifying as “the most profound theologian,” this devil suggests he is the source and enforcer of “orthodox” theology and the institutions that enforce it, echoing the Marcionite Gnostic perspective alluded to in “Berenice”’s invocation of Tertullian.

The tale also links the Devil less to Milton’s Satan than to Milton himself, through his monist materialism, physical blindness and theological insight, anticipating the view of Milton as an “Arian” subverter of orthodox Christian doctrine Poe makes explicit in a combative 1845 review of Griswold’s edition of Milton’s prose works (one of many public disputes that fueled Griswold’s later demonizing characterizations of Poe.)

“Bon-Bon”’s devil is close kin to one of the caricatures Poe intended to frame and narrate his proposed collection, Tales of the Folio Club: one “De Rerum Naturâ, Esqr., who wore a very singular pair of green spectacles,” identical to those of “Bon-Bon”’s devil, again, underlining Poe’s Epicurean agenda. Poe approached the New York publishers Harper and Brothers with a prospectus for this planned collection in 1836, receiving a rejection letter in June of that year that claimed, in part, that American readers “have a decided and strong preference for works, (especially fictions) in which a single and connected story occupies the whole volume, or number of volumes.”

Poe’s pique at this rejection was likely intensified by the advertisements for the many titles Harper did publish that year; among the most prominent was the English natural philosopher and theologian John Mason Good’s Book of Nature, a series of lectures claiming consilience between a Trinitarian protestant understanding of the Bible and natural philosophy. Harper recognized that the long-term saleability of Good’s Book was due to this claimed consilience; the catalogue listings for Good’s Book cites a New-England Christian Herald review, trumpeting it as “a safe book for any person to read. There is no skepticism in it.” Harper’s successful marketing led to this “safe book’s” sustained and widespread dissemination in the United States into the 1870s, especially in the wake of the less orthodox natural theology of the Bridgewater Treatises in the late 1830s and Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation in the 1840s (for more on this, see my article “Entro(Poe)tics: Darkness, Decay and the Heat Death of the Universe.”)

Pym subverts Book of Nature’s claim that the natural world is rife with evidence of a benevolent, omnipotent creator through its eponymous naïve narrator, who constantly misreads a world littered with evidence, instead, of a vengeful, temperamental and deceptive author; the comical Epicurean Devil of the “Folio” tales is replaced by a neo-Gnostic nightmare world that serves as, at once, a “single and connected story” to meet the publisher’s demands, and a mockery of the “single and connected story” that is the specious consilience between Christian doctrine and the study of nature presented by one of Harper’s most profitable titles. Poe ultimately returns to such a theologically subversive “single and connected” story with his cosmic poetic romance, Eureka.

Poe’s 1840 collection, Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque, further shows the evolution of his Romantic Satanism. Consider “The Devil in the Belfry” (1839), in which the Devil becomes one of Poe’s first apparitions of entropy, a companion to the fissure running through the contemporaneous “House of Usher” and a precursor to the later “Masque of the Red Death.” The punctilious citizens of the remote town of Vondervotteimittiss (wonder-what-time-it-is) are primarily preoccupied with clocks and cabbage until the arrival of a devilish fiddler who invades the belltower and rings thirteen o’clock. Here, the titular devil introduces disorder to the town’s tightly ordered system, but in doing so, admits the possibility of change and creativity.

More than his earlier Faustian farces, this tale shows the influence of the German writer-philosophers, August and Friedrich Schlegel, in whose earlier writings Satan figures the freedom, infinity and chaos admitted by the systematically unsystematic exercise of irony. Friedrich Schlegel called irony “the clear consciousness […[ of an infinitely full chaos.” As James Clow puts it, “Schlegel does not really articulate a position … but instead saturates his writing with a self-reflexivity that both performs and explains the philosophical uses of irony.” Poe’s work is rife with Schlegel’s brand of self-reflexive irony, which had earlier influenced the Romantic Satanism of Percy Shelley, whose essay “On the Devil, and Devils” calls Satan “the vulnerable belly of the crocodile” of Christian doctrine, a rebuke of John Mason Good’s Biblical and natural theological views. Shelley’s essay was not published until 1880, making it unknown to Poe. Yet there are striking parallels between the Romantic Satanisms of Shelley and Poe, although Poe ultimately takes Schlegel’s self-reflexive irony much further than his English predecessor in ways that weave his work into the literary foundations of the contemporary Satanic milieu.

“Ligeia,” “Morella” and Poe’s Esoteric Reception

Two other Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque build on the narrative structure Poe initiated with “Berenice,” demonstrating how Poe’s Schlegelian irony led to his work’s embrace as a precursor to what, after Blavatsky, becomes called the “Left Hand Path” of modern esotericism. “Ligeia” and “Morella” are sister-tales of apparent metempsychosis, circulating around an unreliable narrator’s perception that his dead wife’s esoteric studies and tremendous will enable her rebirth into, respectively, the body of his second wife and that of his daughter. These tales shaped the concept of magical will used by later esotericists to distinguish between “right hand” and “left hand” practices, beginning with their adaptation by the African-American occultist Paschal Beverly Randolph, largely responsible for introducing “sex magic” practices to late 19th century audiences.

As Randolph’s biographer John Patrick Deveney explains, “The influence of Poe’s writings on Randolph is quite extensive.” A “constant refrain” of Randolph’s magical philosophy is that “men fail and die through feebleness of will.’” Randolph attributes this idea in his seminal text, Ansairetic Mystery, to Joseph Glanville. The origin of this statement is not Glanville, but Poe’s epigraph to “Ligeia” attributed to him, which bears little relation to Glanville’s theological views. What it does strongly resemble is a stanza from Friedrich Schiller’s poem “Die Worte des Glaubens.” In John Herman Merivale’s 1844 translation:

And God is – a holy Will that abides,

Though the human will may falter;

High over both Space and Time it rides,

The high Thought that will never alter.

Johann Fichte included this stanza at the conclusion of his essay “On the Ground of our Faith in a Divine Government of the World” as exemplary of his own view, fuelling the Pantheismusstreit alluded to in “Morella” as the “wild pantheism of Fichte.” That Poe deploys Fichtean terms in such unsettling ways in these tales, written during the era of the Young America movement and the popularization of “Manifest Destiny,” when Fichte’s nationalist mysticism (which would later infuse Nazi occultism and other forms of radical religious nationalism) was percolating through antebellum American culture surely deserves further consideration, but is beyond the scope of this essay. At base, the Fichtean allusions in both tales emphasize that the human will can, through “intentness,” in effect become divine and abide eternally, facilitating Fichte’s reception as a philosopher of the Left Hand path for later esotericists, from MacGregor Mathers and Crowley to more recent proponents including Aquino and Stephen Flowers.

While originating in Blavatsky’s interpretation of contrastive tantric practices, the terms left- and right-hand path have evolved via later commentators to distinguish those who seek mystical union with the divine by a total surrender of individual self from those who seek to attain knowledge, power, or personal immortality through an act of self-apotheosis. It is exactly such an act that the narrators of “Ligeia” and “Morella” claim to witness in the (however momentary and incomplete) conquest of death performed by their sinister wives.

Conclusion: Eureka, A(Poe)theosis and the Invention of “The Left Hand Path”

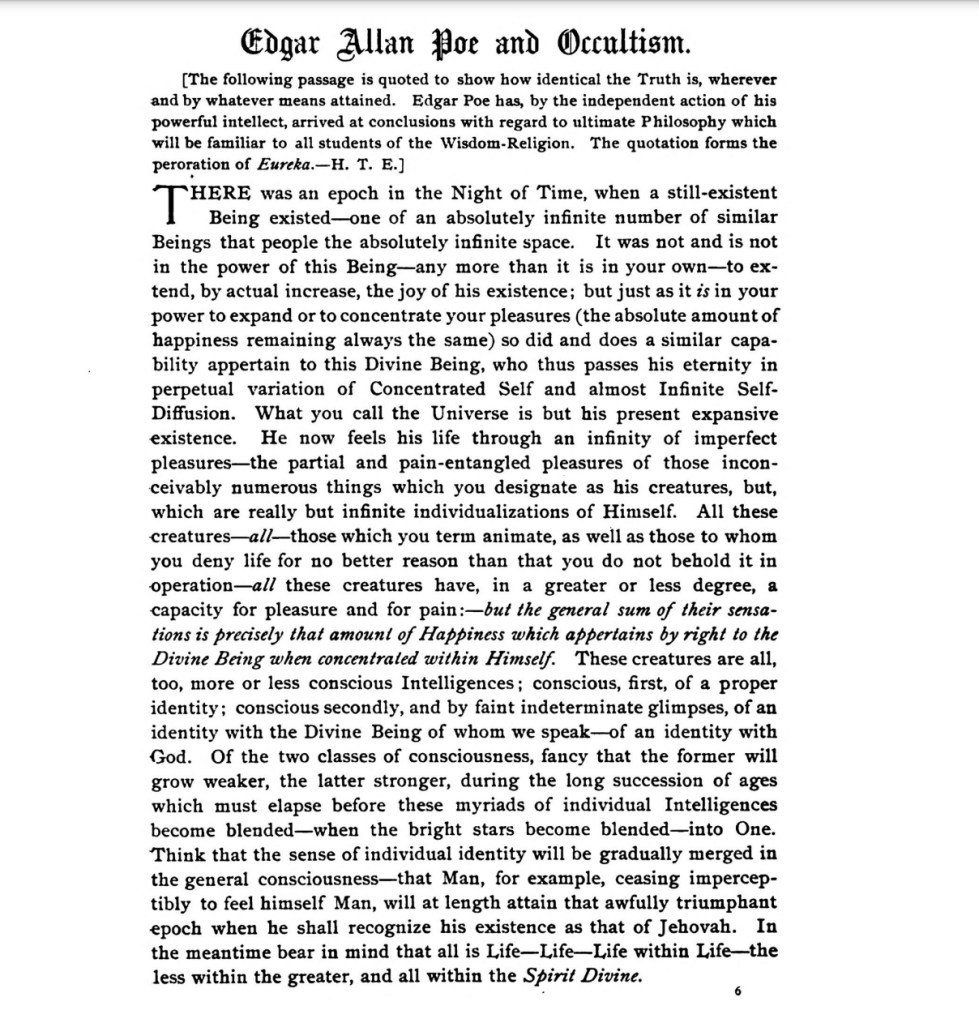

These tales are far from the only writings by Poe to influence the worldview of later esotericists; Eureka has had an even greater influence in this regard. In 1893, the Theosophical Society’s official periodical, Lucifer (Vol. 12, March-August) included the brief article “Edgar Allan Poe and Occultism,” claiming that Poe, “By the independent action of his powerful intellect, arrived at conclusions with regard to ultimate philosophy which will be familiar to all students of the Wisdom-Religion.” It reproduces the passage from Eureka culminating in Man “will at length attain that awfully triumphant epoch when he shall recognize his existence as that of Jehovah.”

Peter Gilmore, current High Priest of the Church of Satan, describes LaVeyan Satanism as not a form of “atheism,” but of “I-theism.” It’s a pun that Poe, as a (witting, willing or otherwise) “Lord of the Left Hand path” and literary architect of modern Satanism, made possible. His identification of divinity with humanity and ambiguous synthesis of Gnostic and Epicurean materials seeded the ground from which both modern rational and esoteric Satanism would spring. From the neo-Gnostic literary Satanism of The Revolt of the Angels, the 1914 Anatole France novel which serves as a core text for The Satanic Temple, to “satanic woman” Maria de Naglowska’s Randolph-inspired surrealist sexual ritualism, to Anton LaVey’s use of Satan as an adversarial floating signifier, Poe’s work has become foundational to an incredible proliferation of Satanic discourse over the last 150 years.