In the world of horror fiction, through the booms and busts, writer, scholar and librarian John Glover meditates on a perennial question….

The idea that publication of horror fiction follows boom and bust cycles is common among the people who make up the field, from writers to readers, from publishers to critics. It’s easy to understand why this view persists, given the rise and fall of the Gothic, the penny dreadful, the pulps, and the horror boom that lasted roughly from 1970 to 1995. Readers and aficionados of the genre are accustomed to saying that all of the above are the same thing, just wearing different masks. While this is true in the sense that similar subject matter and tropes recur through the decades, increasingly I’m coming to question whether horror will survive as a formulation for the literature that most of us recognize under that name, whether Dracula, Psycho, or The Drowning Girl.

Caitlin R. Kiernan has long contested the value of the term “horror” as a generic label.

If it weren’t for the rise of the web and its capacity to perpetuate both communities and content, the term “horror” would largely have fallen out of use by now to describe the genre. As things stand, however, I feel that we’re currently in the middle of two waves of fiction that could rightly be called “horror,” each as similar and distinct as the Gothic and the pulps. One of these waves is essentially the long tail of the last boom, and the other is a new formation built from literary fiction, a new attention to sociocultural concerns, and explicit engagement with the genre’s history. The coexistence of these two waves has caused anxiety in the field, not least because the word “horror” itself became anathema after the market crash of the mid-1990s. Many authors working today take a nuanced approach to writing horror—heavily informed by the lessons of the boom.

One of 2015’s most successful horror novels was, on many counts, Paul Tremblay’s A Head Full of Ghosts. This elegant tour de force is graced with both literary style and genuine unease, revolving around a case of suspected possession and a family forced to turn their lives into a media spectacle in the hope of saving their daughter. It quite clearly belongs to horror, drawing on such sources as The Exorcist and the reflexive frights of Scream, featuring a narrative self-awareness based out of reality television and social media that can stand comfortably with literary conceits stretching back through the history of narrative. The fabric of the book is woven from after-action discussions between the protagonist and her literary documentarian, and blog posts analyzing the abortive documentary filmed during the events around which the novel centers. The novel shifts easily back and forth between exposition, recollection, and introspection. These many layers are critical to the book’s success, and leading it to be described in one review as “smartly, viscerally [exposing] the way mass media, the Internet and pop culture have transformed our experience of that primal human impulse, horror” (Heller).

How else can we tell that A Head Full of Ghosts is a horror novel? As of this writing it is a candidate for a Stoker Award from the Horror Writers Association, for Superior Achievement in a Novel. Users of the social reading website Goodreads identified the novel as “horror” more frequently than any other genre. Finally, none other than Stephen King said that it “scared the living hell out of me, and I’m pretty hard to scare.” Awards, readership, and influential voices all indicate that this novel belongs to the horror field.

All of that said, A Head Full of Ghosts was published by William Morrow, a HarperCollins literary imprint. While this high-visibility publication has been cause for celebration among horror writers who aspire to broadly successful authorial careers, HarperCollins has avoided the H-word in describing it (though the imprint does in fact publish works it categorizes as horror). What does it mean for a novel to succeed in a genre to which its publisher does not necessarily feel it belongs? Tremblay himself has diverse interests and a genial social media presence that connects with longtime horror authors and professionals… as well as musicians, educators, literary authors, and all manner of people involved in the book trade. He does not seem to me to resemble the bulk of authors prominent during the boom, who in profiles and interviews were likely to cite a narrower set of influences and interests: Bram Stoker, H.P. Lovecraft, Richard Matheson, and so on.

Authors continually remix literary genres, of course, and genres go in and out of fashion, but both Tremblay and his Head Full of Ghosts exist in two (or more) separate spheres of horror. A quarter century after the boom, one might expect to see a resurgence of horror in a new generic formation. That has happened in the guise of things like “zombie fiction,” and a healthy stripe of dark YA, and horror novels that fly under different colors for any number of reasons, but it has also not happened, insofar as substantial numbers of people still read, write, and talk about “horror.” Here I will leave Paul Tremblay as case study, but it seems worth saying that he has good company in the sundry contemporary authors who exist in a state not entirely unlike that of Schrödinger’s Cat, being both horror authors and not-horror authors.

If there’s something distinctive about the horror genre, starting around 1970 and ending in the mid-1990s, it seems useful to discuss that time frame. Various books have been associated with the start of the boom: Rosemary’s Baby in 1967, The Exorcist in 1971, Carrie in 1974. All make reasonable candidates for signposts, and certainly there was a market for short horror fiction at the time, including men’s magazines and fantasy and science fiction publications that occasionally published horror.

What is somewhat harder to pin down is precisely when the idea of a “horror author” or “horror writer” emerged. While many authors wrote horror stories of one kind or another prior to 1970, the concept of an author who was segregated from others by the adjective was not common. I’m not going to say that no one called herself a horror writer prior to any particular date, as that would require exhaustive searching to prove a fairly small point. I do think it’s notable, however, that the MLA International Bibliography, WorldCat, and Google Books include virtually no mention of a “horror writer” or “horror author” prior to 1960, and barely any prior to 1970. None of those sources are without their problems, but for all that we have supposedly always had horror fiction, it’s interesting to me that we have not always had horror authors. Not until the late 1970s and 1980s do we really see the idea gain traction, coinciding with the rise of postmodernity in the U.S., the consequent broadening of the canon, and the mass market success of horror fiction.

The end of the boom has been discussed by countless writers, editors, and anthologists, from the end of Zebra Books to the glut of vampire fiction, and I see no need to cover it again here. Scholarly work in this area, however, has been limited. The best study thus far published about the horror boom as a phenomenon unto itself is Steffen Hantke’s 2008 article about Dell’s Abyss imprint and the decline of literary horror in the 1990s. By focusing his work on an imprint exceptional in its time, publishing substantial numbers of female horror authors who wrote in anything but demotic style, Hantke anticipates concerns and disputes that have taken on greater resonance than ever in recent years (64).

In an essay based on a speech he delivered at the 1998 Horror Writers Association Bram Stoker Awards Banquet, Douglas E. Winter discussed at length the rise and fall of the category of “horror” publishing, and how such authors as William Peter Blatty or Jack Williamson did not write books that went under that name. He called this kind of writing “a progressive form of fiction, one that evolves to meet the fears and anxieties of its times,” and claimed that “[w]hat we are witnessing, then, is not the ‘death of horror,’ but the death of a short-lived marketing construct that, although it wore the name of “horror,” represented but a sideshow in the history of the literature” (Winter).

Can we really call “short-lived” a period of vigorous literary productivity that lasted at least a quarter of a century? I don’t think so, and I think it becomes more problematic if you start from the position that there are meaningful differences between Gothics, Victorian ghost stories, pulps, the mid-century fiction of Richard Matheson and Shirley Jackson, and so on. To say that it’s “all horror” makes some sense to me as a reader, because it’s what I personally seek out, and this is supported on some level by books like Becky Siegel Spratford’s The Readers’ Advisory Guide to Horror, one of a class of tools designed to help librarians understand genres and make recommendations for library patrons looking for something to read. The same is true of surveys of the genre like Gina Wisker’s Horror Fiction, which seek less to parse out than to provide a rich overview of the full progression of the literature of fear in its different phases. Useful rubrics for broad understanding or guides for literary taste, however, will not necessarily provide the best guide for periodization.

A significant turning point in the horror boom was the formation of a professional organization devoted to writing horror. The Horror Writers Association met for the first time in 1985, spurred by a sense of shared interests and a need for a professional organization, among other things. The story of its founding, originally as the Horror and Occult Writers League, has been documented many places, but the timing generally seems to come in for little discussion (perhaps a mercy, given what was to follow). Not many years after the field started taking on the trappings of other popular genres like fantasy and science fiction, romance, and mystery, the market started to wane. It didn’t happen overnight, and it didn’t happen totally, but this newly organized group of professionals was to some extent deprived of their newly catalyzed profession. Notables like Ellen Datlow, Stephen King, Anne Rice, or Peter Straub were able to persevere, but countless others changed genres, switched to other kinds of writing, or left the field.

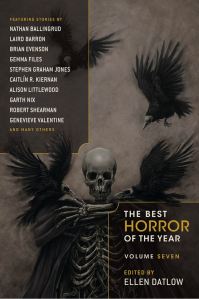

What happened after that was predictable in some ways, less so in others. Writers who wanted to write fear-inducing fiction found other niches where they could do that. Sometimes that meant small press and markets paying well below professional rates, if they were free to write at that level or driven to it by their own natures. Others found welcome audiences in other genres for darker spins on the thriller or fantasy novel. Small presses variously endured, failed, or appeared, and the last decade has seen a surge in new markets for dark fiction. The Stoker Awards given by the HWA did not vanish with the mass market, and neither did World Horror conventions. Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling, who in 1988 launched their summative anthology series, The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, did not call a halt when the field was in a down-swing. Datlow currently edits The Best Horror of the Year, a summative anthology that she launched solo in 2009 after the final volume of Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, and her work has been joined over the years by similar volumes focusing on horror, dark fantasy, weird fiction, and so on.

What also happened after the boom was that many of the people who were part of it, both the professionals and the readers, stayed together in various ways. Some of that resembled historical activities of fans in other genres, such as fanzines and letter-writing, but some of it was not as readily possible after previous literary markets waned. Many members of the horror community stayed connected online via Usenet, chat rooms, message boards, blogging platforms, and all of the social media that have come since. Even with the most powerful signifier of the time, the word “horror,” largely erased from the market, it was possible for the people of horror to stick together as never before. This reaffirmed the existence of both their community and the horror field, even when that field at times looked very sparse.

Earlier I claimed that there are two separate waves of horror fiction ongoing today. The more recent one is characterized by authors like Laird Barron, Stephen Graham Jones, Caitlín R. Kiernan, John Langan, Livia Llewellyn, Nick Mamatas, Helen Marshall, Simon Strantzas, or Paul Tremblay. These authors have by and large been heavily influenced by mainstream literary or academic writing cultures, are socio-politically aware in ways that carry over to their fiction, business practices, or both, and occasionally write metafictional or otherwise highly reflexive stories that engage with the genre’s history.

The other wave, the long tail of the boom, is visible in many places. Publishers like Centipede, Subterranean, and Valancourt are reissuing work from the boom, sometimes in revised or expanded versions. In other cases they are releasing sequels to or alternate versions of decade-old horror novels that have enough of a potential readership that publishers can afford to invest in sometimes lavish editions. Even allowing for the vagaries of memory and searching on the Web, it is easier than in decades past to dive into the memorabilia, fan reports, photographs, and retrospectives associated with the boom. This sustaining of the aesthetic of the boom undoubtedly has fed into the success of any number of recent publications, from presses large and small or authors who self-publish.

Is this a genuine continuation of the boom, or just an outsized case of nostalgia? I’m not sure, but there is a wider range of awards for the horror field these days, and it often seems like significantly different groups of authors and kinds of fiction are associated with different gatherings, whether it be World Horror, Readercon, NecronomiCon, or Necon. In future, I would like to examine more thoroughly the awards, nominees, and guests at such events, and attempt to map the different spheres of the genre, associated with the boom or otherwise.

In a nice irony, the thriving Nightmare Magazine regularly runs a column entitled The H-Word. It consistently features thoughtful commentary from authors across the spectrum of horror. Explicit engagement by professionals writing today under a column bearing a title that was at one point a joke is perhaps indicative of the field’s ability to cope with an ongoing state of flux better than during past publishing cycles.

Where does that leave us? On the one hand, it’s easy to locate published fiction that rests comfortably cheek by jowl with the horror of the boom, whether in anthologies, magazines, or novels. On the other, it’s also easy to locate anthologies, magazines, or novels that partake of horror while eschewing the H-word, whether as prominent as a novel like A Head Full of Ghosts or otherwise. The rise of transmedia spectacles like The Walking Dead lies in this camp to some extent, insofar as one can spend hours trawling through reviews and critical articles describing it as “dark drama” or the like, before getting to anything that will call it without adjective or concession simply “horror.” Whether this reflects actual animus against horror is difficult to say, but it does confirm that some people perceive one term as significantly more useful than another, decades after the boom.

If my portrayal of this situation of two ongoing waves of horror fiction is accurate, are they going to end? Can we still talk at this point about the cyclical nature of the field, in a world where micro-presses, boutique presses, Kindle, and other means can keep a genre rolling along in some capacity as long as there are customers ready to buy? It may be that we are not, as many have argued, in any sort of golden age or temporary efflorescence, but have actually entered something like a steady state where nothing ever dies.

If I were to point to a marker indicating anything like relative ill health in horror fiction, I might point to changes in the scholarship. A recent Call for Papers that went out on academic discussion lists for a “monster studies” conference session did not use the word horror at all. Likewise, the Horror Literature section of the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts is smaller than it used to be, partly because some members of the association choose to talk in other genre contexts about subject matter that many have seen as belonging to horror. The existence of scholarship is, of course, not a precondition for the existence of the fiction it treats, but it is part of the swirl of the literary ecosystem—reviews, criticism, fandoms, and so on—that reflects the life of fiction once it has left the bookstore or library.

In 2015 I attended the World Horror Convention, still one of the major gatherings for professionals in the field. Panel discussions were vigorous, energetic, and spoke to ongoing engagement with horror and serious questions about what horror is or is not, should be or should not be. This gathering seems to me to be in relatively good health, although the impact of this year’s division of the event into an awards weekend in Atlanta and a convention in Las Vegas, held within days of each other, is yet to be seen.

On the other hand, I recently ended a two year term on the Board of Directors of James River Writers, a thriving literary organization based in central Virginia. In that time, never once did I hear attendees discuss horror fiction at our events, which include a sizeable annual conference that actively works to accommodate writers of YA, erotica, romance, other genres not always welcome in “serious” literary circles. On those occasions when I talked with members of the organization or visitors about what I write, the conversational ground inevitably became shaky the moment I trotted out the H-word. In the most memorable of these interactions, the woman I was speaking with said that her daughter liked Twilight and vampire books. I said that I could appreciate that, because I wrote horror. She hesitated for a long time, but eventually she said that she didn’t usually think about people writing horror, and that you usually thought about horror movies. While this conversation may simply reflect lack of awareness, it suggests to me the possibility that for some people, from experienced readers to novice authors, the subject matter of horror exists, but not necessarily a living genre entirely devoted to ghosts, zombies, vampires, werewolves, serial killers, haunted houses, the occult, and so on.

At the end of the day, I’m not suggesting that we should attempt to rename the genre or the study of its literature. I do, however, think that we should be cognizant of the extent to which the horror boom shaped the way that we consider, write, and write about horror fiction. While I am not prepared to say that M.R. James, H.P. Lovecraft, or Shirley Jackson did not write horror fiction, I am coming to believe that it’s anachronistic to talk about any of them as being horror writers. Our tendency to do so is a byproduct of our own moment in the history of the literature of fear.

Acknowledgments

I presented an earlier version of this at ICFA 37 as “Anxiety, Nomenclature, and Epistemology after the Horror Boom,” where the audience had many helpful comments and useful queries. I am grateful for criticism from Lindsay Chudzik, Mark Meier, and Sean Moreland, all of which helped to strengthen the work, and to s.j. bagley for many thought-provoking conversations about the boom. Finally, I am grateful for the support of my employer, VCU Libraries, in pursuing my scholarly interests.

Thinking Horror, volume 1, edited by s.j. bagley and Simon Strantzas

John Glover is a librarian at Virginia Commonwealth University, where he supports humanities research and instruction, contributes to various digital humanities projects, and studies quaint and curious volumes of forgotten lore. He has chapters forthcoming on Supernatural Horror in Literature and Laird Barron’s Old Leech stories. He also studies the research practices of writers, and last year he co-taught “Writing Researched Fiction” in VCU’s Department of English. He publishes fiction and literary essays as “J. T. Glover,” and his work has appeared or is forthcoming in Pseudopod, Thinking Horror, The Lovecraft eZine, and Nightscript, among other venues.

John (aka J.T.) Glover