This post is based on the conference paper I delivered as part of the Henry Armitage Symposium, the academic track of NecronomiCon, held in Providence, RI, from August 15-18, 2024.

Abstract (TLDR!)

In order to better understand the extent and importance of Lovecraft’s conception of “cosmic horror,” we need to recognize it as a transvaluation of a term already widely circulating in the first thirty years of Lovecraft’s life. During this era, the term “cosmic horror” derived primarily from the (at the time, highly influential) writings of American physician, ophthalmologist and medical lexicographer, George Milbry Gould. This short essay builds on one small part of the larger argument of “The Birth of Cosmic Horror from the S(ub)lime of Lucretius,” included in the essay collection New Directions in Supernatural Horror Literature, published by Palgrave in 2018 (if you’re looking for a peer-reviewed and properly citational version of the basic argument, use that.) I develop these connections further and more formally in my in-progress book, which offers a literary-historical genealogy of cosmic horror.

“The eternal silence of these infinite spaces fills me with dread”

Since the mid 20th century, the phrase “cosmic horror” has been closely associated with the writings of H.P. Lovecraft. While Lovecraft’s critical and fictional writings did much to popularize the phrase and develop the concept of cosmic horror as a literary mode closely linked to a philosophical perspective, both the phrase and the emotion it designates have a much older and broader history. For example, American horror writer and philosophical pessimist Thomas Ligotti looks back to the writings of French scientist and Christian philosopher Blaise Pascal for an early modern conception of cosmic horror. Pascal wrote of his a sense of being “engulfed in the infinite immensity of spaces whereof I know nothing, and which know nothing of me; I am terrified. The eternal silence of these infinite spaces fills me with dread.” In Ligotti’s words, “Pascal’s is not an unnatural reaction for those phobic to infinite spaces that know nothing of them.”

“The S(ub)lime of Lucretius“

I’ve elsewhere argued that one can look back further and find a close conceptual and affective kin to what Lovecraft calls “cosmic horror” in the ancient world; namely, the reception of the Latin epic didactic poem De Rerum Natura by Lucretius, whose presentation of a fluctuating universe arising from the unpredictable encounters between atoms falling through the void occasioned a reaction of mingled awe and horror from both many pagan and Christian writers of late antiquity (such as Cicero and Ovid on the one hand and Lactantius and Prudentius on the other), a reaction echoed by early modern writers including Thomas Hobbes, Lucy Hutchinson and John Milton, Gothic novelists including Horace Walpole, Mary Shelley, Marie Corelli, and eventually, even Lovecraft himself, who by the 1930s repudiated his intense self-identification with Epicurean philosophy due to the foundational role the unpredictability of the clinamen, or atomic swerve, played in its metaphysical materialism, expressing a reaction of abject horror that ironically echoed that of most earlier theistic commentators (see my essay, “The Poet’s Nightmare: The Nature of Things According to Lovecraft.”)

“Anomalous Sources“

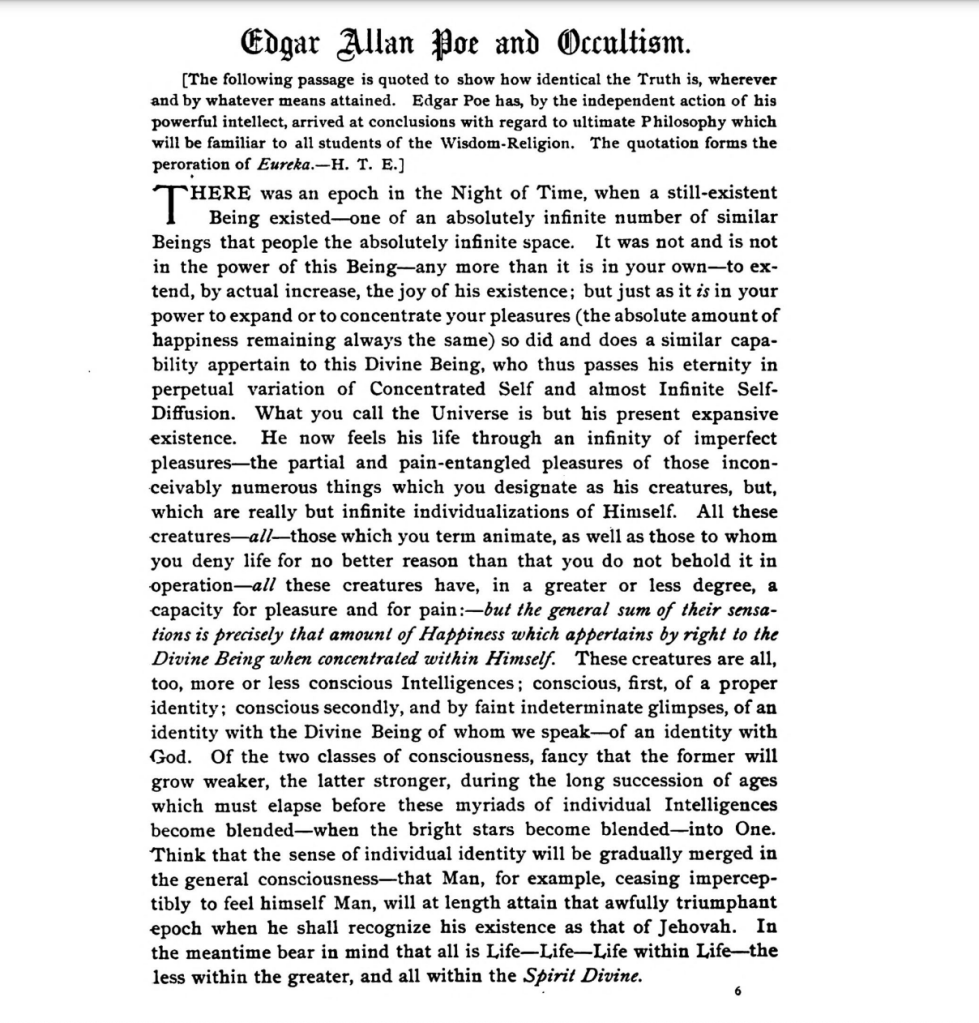

My focus here is more narrowly on the conception of cosmic horror that prevailed during the decades leading up to Lovecraft’s revaluation of the term; this conception was one advanced by George M. Gould. I’m not the first to point out Gould’s pre-Lovecraftian use of this term, although I am the first to explore its influence and significance. In a 2015 editorial, Paul Di Filipo explains that this literary mode is “sometimes dubbed ‘Lovecraftian fiction’ in honor of its most famous exponent …whose work helped to crystallize and codify the subgenre,” but also notes that the “phrase itself predates Lovecraft, being found even in such anomalous sources as George Milbry Gould’s (1848-1922) The Meaning and the Method of Life: A Search for Religion in Biology (1893).

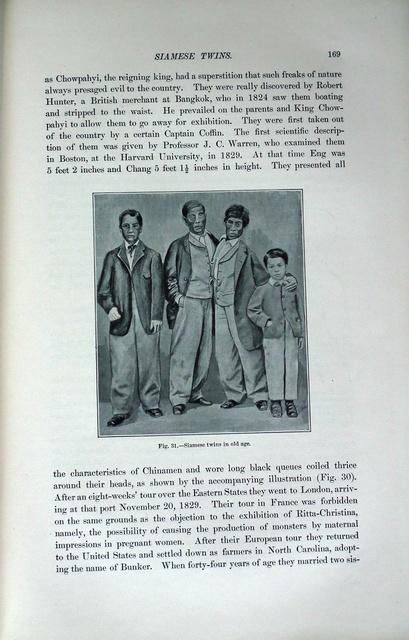

Di Filipo’s characterization of “cosmic horror” in Gould’s writings as “anomalous” is ironic for two reasons. First, it reflects the reality that Gould remains most famous for his 1896 compendium, Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine, a compilation that would remain at once a standard medical, and a widely popular, reference work for half a century. Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine has directly influenced a number of 20th and 21st century works of horror fiction, having often been used as a source of inspiration by writers and film-makers. For example, it was the source through which numerous horror creators found the apparently apocryphal case of Edward Mordrake, whose horrible story has inspired tales by Robert Bloch, episodes of TV series including Tales from the Crypt and The X-Files, and James Wan’s film, Malignant (2021.)

Second, di Filipo’s quip suggests that Gould’s concept of cosmic horror, unlike Lovecraft’s, is something of an oddity or outlier. In fact, while it has been almost entirely eclipsed by Lovecraft’s since the 1940s, it was widely influential from the early 1890s until the 1920s, and the subject of debate in medical, natural philosophical and theological discourses during that time. Gould wrote about cosmic horror frequently, not just in specialist medical and theological venues, but in widely read popular periodicals like The Atlantic. Gould’s conception of cosmic horror should thus be of interest not just to students and scholars of Lovecraft, weird and horror fiction, but should also interest students and scholars of early 20th century American history, the history of medicine and the medical humanities.

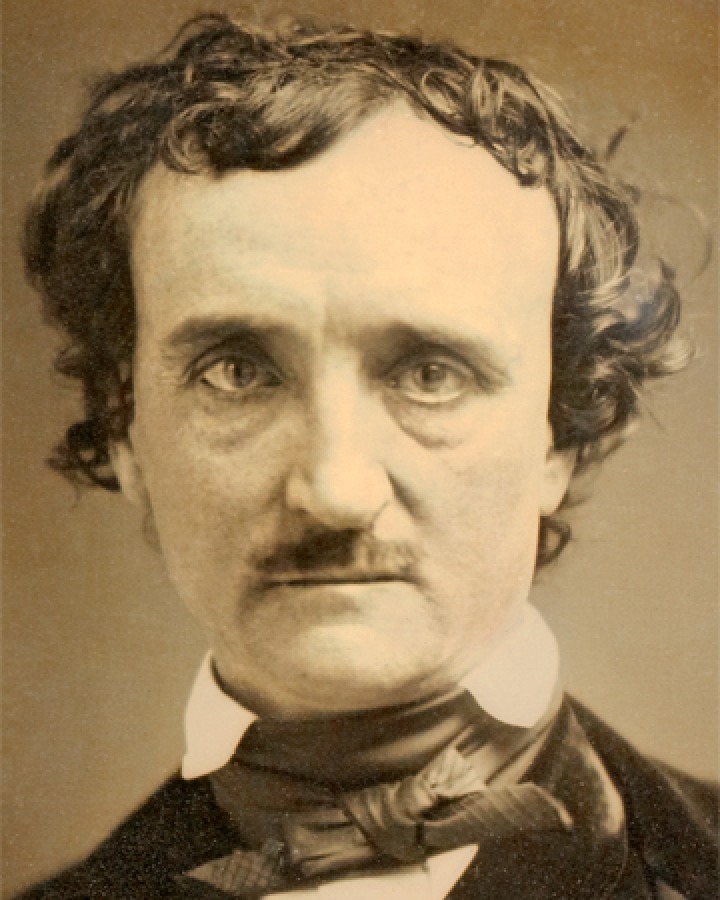

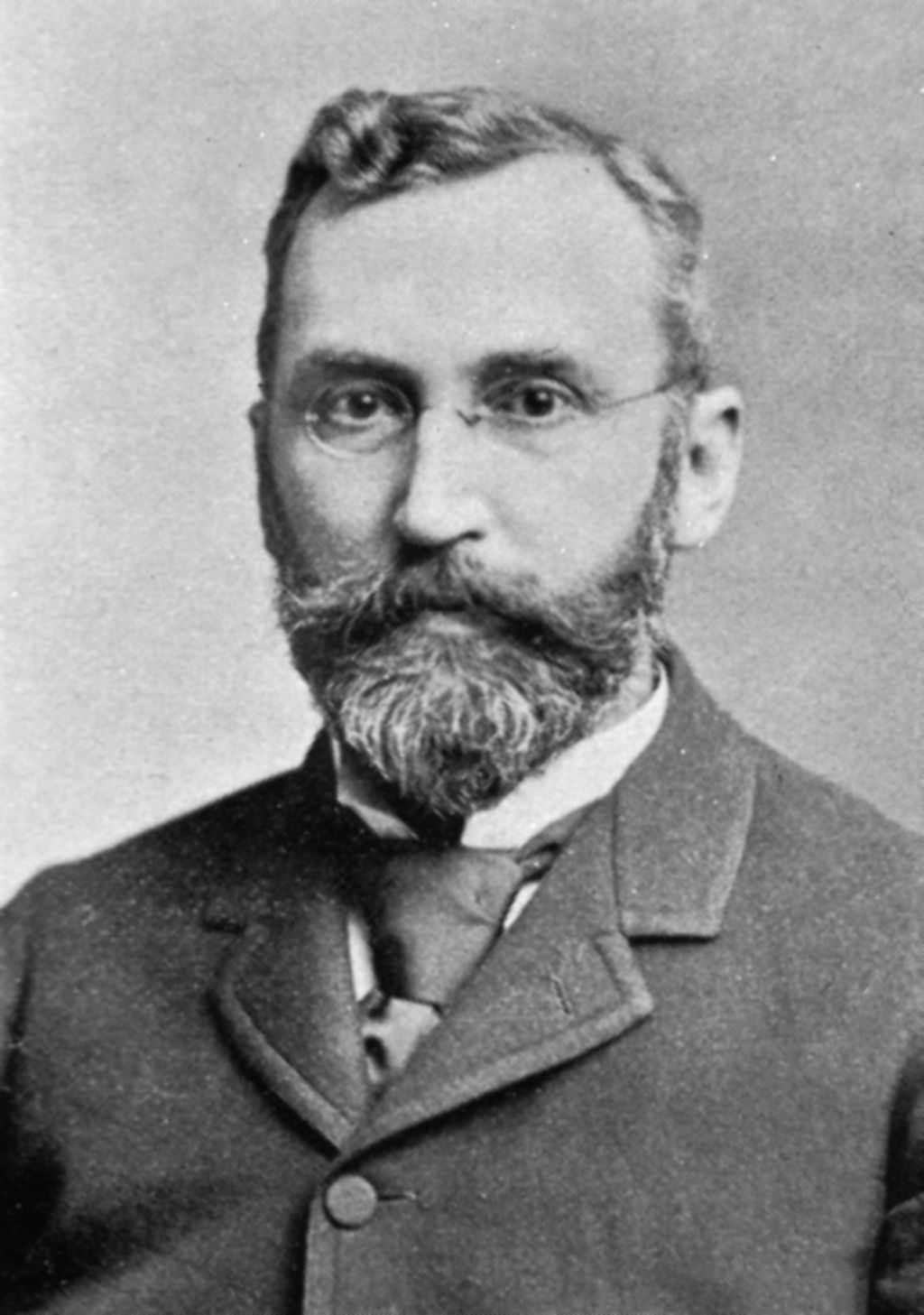

George M. Gould

Gould served the Union in the Civil War and his youthful war experiences shaped his outlook, feeding his interest in both medicine and theology. These interests led him to study theology at Harvard Divinity School and later to study medicine at Jefferson Medical College. He graduated in 1889 and opened an ophthalmology office in Philadelphia, where one of his first clients was the poet Ezra Loomis (later better known as Ezra Pound) who would subsequently recommend Gould to James Joyce, who suffered from a variety of ocular problems. Gould edited the Medical News (1891-1895), the Philadelphia Medical Journal (1898-1900) and American Medicine (1901-1906), earning numerous offices and honors over the course of his career. During this period he also exchanged many letters with his older contemporary and fellow “literary physician” S. Weir Mitchell, best remembered for the “rest cure” treatment to which he subjected Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

“Morbid Vision”

Gould wrote most often on ophthalmology, but his legacy as a medical lexicographer is broad. His medical dictionaries sold nearly a million copies and he was also a prolific author of various literary works, including poetry and a series of what he called “biographical clinics,” or diagnostic biographies of famous artists and intellectuals, including Charles Darwin, Thomas de Quincey, and Gould’s friend and sometime correspondent, the writer Lafcadio Hearn. Gould’s “Biographical Clinics” often conclude that the peculiar perspectives of these influential figures is linked to their ocular abnormalities; he believed that “morbid vision” often leads to a “morbid metaphysics.” Indeed, for Gould, the eye was best understood as the external portion of the brain, and he pushed the connection of literal vision to rational thought to extremes – the eyes, for Gould, came to occupy a position of metaphysical privilege, much like the penis for his Viennese contemporary, Freud.

An excerpt from Gould’s study of Hearn illuminates how closely linked his concept of cosmic horror and diagnostic practices were:

“Hearn was no “product of his environment… The great, the distinctive, the dominating force which controlled and created Hearn’s literary makings, his morbid vision, was not “environment” as the critics and scientists mean by the term. These have not yet learned that Art and Life hang upon the perfection and peculiarities of the senses of the artist and of the one who lives, and that intellect and especially aesthetics are almost wholly the product of vision. Conversely, the morbidities and individualisms of Art and Life often depend pre-eminently upon the morbidities of vision.”

Hearn and the “new pathology of genius”

Gould saw Hearn as exemplifying “a new pathology of genius …coming into view which shows the morbidizing of art and literature through disease, chiefly of the sense-organs of the artist and literary work-man, but also by unnatural living, selfishness, sin, and the rest.” Gould presents Hearn’s personality and writings (in which Lovecraft also found an anticipation of cosmic horror) as characteristic of this modern morbidity, and claims he influenced Hearn’s decision to relocate permanently to Japan. Hearn had in common with both Gould and Lovecraft a suspicion of and even contempt for modern, urban, cosmopolitan industrial life, and Gould suggests that Hearn’s embrace and adaptation of ancient East Asian folklore and traditions offered a means of moving beyond the paralyzing cosmic horror he experienced, a horror that suggestively haunts his earlier American writings, including the Louisiana-set early novel Chita (see Peter Bernard’s essay “Some Notes on Reading Hearn’s Chita as a Gothic Text.”)

It is important to recognize that, like Lovecraft’s later revaluation, Gould’s concept of cosmic horror is a polemical interpretation of a particular, but supposedly universal, human affect, using a phrase that was already circulating through late 19th century transatlantic anglophone print culture. The earliest use I’ve found of the phrase “cosmic horror” via Google’s Ngram Viewer occurs as part of a journalistic description of the period leading up to the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883: “We could feel that some cosmic horror was impending long before the catastrophe took place, and I fancy that other sensations of a like nature are in store. We hear from one part of Asia of atmospheric phenomena which disturb numerous and delicate people.”

From this apparently first reference in the Pall Mall Gazette ten years before Gould publishes The Meaning and the Method of Life, and nearly a half-century before Lovecraft re-defines it in his essay Supernatural Horror in Literature, the term “cosmic horror” was associated with an atmosphere, in the most literal sense, one that “delicate” people were especially responsive to, and one involving a disturbing intimation of threatening immensity.

The Unseen Universe?

The definitions of “cosmic horror” developed by both Gould and Lovecraft are indelibly shaped by late 19th and early 20th century debates about the relationship between scientific and religious worldviews in the spreading wake of Darwinian evolutionary theory and the second law of thermodynamics. They are also contrasting polemical forays into these debates, which led to the publication in 1875 of The Unseen Universe: or Physical Speculations on a Future State, which begins by declaring: “Our object, in the present work, is to endeavour to show that the presumed incompatibility of Science and Religion does not exist”.

The Unseen Universe was the work of two scientists who were also pious Presbyterians, Peter Guthrie Tait and Balfour Stewart. They wrote the book as a rejoinder to “contemporary deployments of the doctrine of the conservation of energy in support of materialism, deployments which presented it as a grand overarching principle that brings all phenomena under the uniform reign of physical causality.” Tait and Stewart’s strategy was not to challenge the first and second laws, but rather to endorse them as evidence for a benevolent divine creator. As they put it, ‘the visible universe must, certainly in transformable energy, and probably in matter, come to an end. We cannot escape from this conclusion. But the principle of Continuity upon which all such arguments are based still demanding a continuance of the universe, we are forced to believe that there is something beyond that which is visible.’ Tait and Stewart made no secret of the fact that their motivation for all this speculation was theological, asserting: ‘We assume as absolutely self-evident the existence of a Deity who is the Creator of all things.”

The Unseen Universe remained influential across the later nineteenth century, being particularly popular with Christian theologians, natural philosophers, and scientists. It was also widely adopted by spiritualists, esotericists and mystics as a means of reconciling metaphysics with modern energy science; warmly embraced by Helena Blavatsky, it became a key text for Theosophy. It was also met with a great deal of criticism from scientists and philosophers.

Clifford’s “Cosmic Emotion”

Among its most forceful critics was the British mathematician and philosopher William Kingdon Clifford (1845-1879). His 1875 appraisal for the Fortnightly Review emphasized the “machinery of Christian mythology” that drove the book, which he (correctly!) predicted “will be warmly welcomed and widely read by those whose dearly-loved convictions it is designed once more to prop.” In philosophical circles, Clifford remains best known for a paper, spurred by his reading of The Unseen Universe, ‘On the Ethics of Belief’ in which he argues that we have not simply an epistemic but also a moral duty to confine our belief to what is warranted by evidence, an essay that would inspire William James to write his own rejoinder, The Will to Believe (1896).

In 1877, Clifford published a related essay that would give rise to both Gould and Lovecraft’s conceptions of cosmic horror. “The Cosmic Emotion” “outlines the ancient conception of nature as an orderly system… as times have changed so have our ideas … replacing the providential plan of some transcendent deity with a scientifically discoverable system of natural evolution. The divine logos of the ancients, we moderns conceive as evolution.” Clifford explains:

“By a cosmic emotion—the phrase is Mr. Henry Sidgwick’s—I mean an emotion which is felt in regard to the universe or sum of things, viewed as a cosmos or order. There are two kinds of cosmic emotion—one having reference to the Macrocosm or universe surrounding and containing us, the other relating to the Microcosm or universe of our own souls.”

Clifford calls it “the cosmic emotion,” rather than specifying what emotion it is, because “the character of the emotion with which men contemplate the world, the temper in which they stand in the presence of the immensities and the eternities, must depend first of all on what they think the world is.” In other words, whether the cosmic emotion is awe or terror depends on how “the world,” reality, is understood, an understanding that changes drastically with historical and cultural context and the development of scientific knowledge: “Whatever conception, then, we can form of the external cosmos must be regarded as only provisional and not final, as waiting revision when we shall have pushed the bounds of our knowledge further away in time and space.”

“That volcanic shuddering and sickening of the soul”

Gould’s fascination with Clifford’s concept and debt to The Unseen Universe are alike clearly evident throughout The Meaning and the Method of Life, in which he writes the following breathless and adjective-laden description, which so tellingly anticipates the language of many of Lovecraft’s horror-struck narrators:

“Until I reached the vivid knowledge of the foregoing truths these two things were precisely they that inspired me with that utter desolation of despair I have called cosmic horror—that volcanic shuddering and sickening of the soul at the contemplation there without of the awful infinity of the dead, cold and purposeless universe; whilst within, an unknown God, by an unknown instinct, commanded an unknown self to do an unknown duty. I have learned that many another sensitive despairing soul, in the face of the glib creeds and the loneliness of subjectivity, has also and often felt the same clutching spasm of cosmic horror, the very heart of life stifled and stilled with an infinite fear and sense of lostness. But I can now lie and look into the starry depths of space without soul-sickening or spirit-shudder, for knowledge lends comfort even to fate, and the certainty of the vision and love of God in the world about and within me translates the stern command of duty into a sweet and irresistible invitation of the Father to help Him.”

Gould designated this evolutionist deity Biologos, claiming that “He Himself may also be a divine victim of some “struggle for existence.” The thought may make us shudder as if icy-steel were in our soul, but every deep spirit has often felt the sudden sickening cosmic horror and chill as the infinite doubt of stability clutched his palsied heart while peering tremblingly over the crumbling precipice of supposed certainty into the abyss of past and future night.”

“Morbid Metaphysics” vs. “Biologos”

Gould insisted that the revelations of the new sciences, like the horrors of the Civil War, could only be borne and made intelligible by faith in a benevolent natural divinity, one whose governance, much like American democracy, required human effort and participation. His attempt to mingle monotheism with evolutionary biology also involved an attempt to reconcile the turn of the 20th century’s two most influential theories about the origin of terrestrial life; xeno-panspermia (basically, all earthly life originating from space-borne alien seeds) and abiogenesis ( all earthly life gradually arising from non-living matter, especially organic compounds.) In Gould’s synthesis, “not matter-born but matter-taming, Biologos came to our planet from without, whether, as has been taught, gaining the first foothold by means of a meteor-carried cluster of organic cells, or whether such an elementary organism were nursed and fanned into activity here in the warm ooze of some tropic shore, matters not. Life’s organizing architectonic force is so profoundly unlike any mechanical force that the materialist of our day can only command our sincere pity for his congenital atrophy of perception. “

In Gould’s conception, cosmic horror is a base material that “man’s sense of law” must sublimate by affective alchemy into an elevated “ceaseless awe.” For Gould, the inability to reach such “sublime pleasure” indicates “a morbid metaphysics.” The overcoming of such “morbid metaphysics” and transcendence of cosmic horror, requires recognizing and accepting the invitation of Biologos, and working with this purposive intelligence to further transform the alien stuff of mere matter. This medical theology led Gould to advocate for eugenic policies: “Future sociology and government must undertake a certain ordering and regulation of the reproductive function. God is waiting to turn the task over to man.”

This “task” is underlined by Gould’s preface to Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine (1896), whose comprehensive catalogue of medical abnormalities and monstrosities is meant to allow readers to “catch forbidden sight of the secret work-room of Nature, and drag out into the light the evidences of her clumsiness, and proofs of her lapses of skill,–evidences and proofs, moreover, that tell us much of the methods and means used by the vital artisan of Life,–the loom, and even the silent weaver at work upon the mysterious garment of corporeality.”

Gould’s cataloguing of medical anomalies was a decisive influence on his conception of Biologos as a constrained deity, working with recalcitrant materials, requiring the cooperation of His human creations to complete the “vitalization of dead matter and mechanical nature,” a view he used his considerable influence as a medical writer, editor and lexicographer to promulgate.

Gould’s “Biologos” was taken up by other writers through to the 1920s (for example, it features prominently in Theodore Dreiser’s 1915 novel The Genius) and became one among many popular attempts to synthesize Darwin and Christianity in the era of the Scopes Monkey Trial, anticipating many versions of “intelligent design” which persist today.

Cosmic Horror: Lovecraft’s Transvaluation

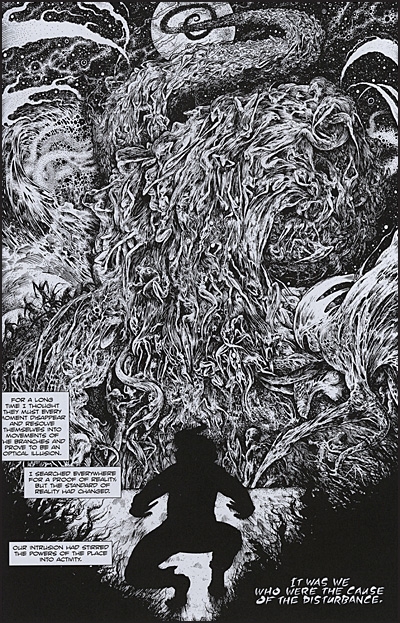

Probably the most direct and best documented literary source of Lovecraft’s conception of cosmic horror is Blackwood’s “The Willows,” which Lovecraft described as the “foremost” of Blackwood’s fictions for the “impression of lasting poignancy” it evokes.

“The Willows” details “a singular emotion” closely related to, but distinct from, natural sublimity, in which “delight of the wild beauty” mingles with “a curious feeling of disquietude, almost of alarm” that “lay deeper far than the emotions of awe or wonder,” due to the narrator’s “realization of our utter insignificance before this unrestrained power of the elements.” The primary difference between this and Gould’s description of cosmic horror is that Blackwood presents a simultaneous commingling of horror and awe, rather than the resolution of the former into the latter.

Lovecraft consistently follows Blackwood in presenting cosmic horror as a “sense of awe” “touched somewhere by vague terror,” and thereby implicitly rejects the “sublime turn” which is the conceptual crux of Gould’s theologically freighted concept.

For Gould, cosmic horror is a pathology and an obstacle, one that must be overcome by faith in the natural divinity Gould calls Biologos. For Lovecraft, it is instead an ambition and an invitation to the speculative exploration of the consequences of a vast, complex and indifferent universe. Lovecraft applies this transfigured conception to works of literature and art that convey the abyssal contrast between a belief in human exceptionalism grounded in the persistent, palliative notion that we are made “in the image” of a benevolent creator, and the reality that we are but one species among tens of thousands, struggling for survival on one planet among millions, in a universe whose virtually infinite reaches are beyond our paltry epistemic grasp, and from which we will one day pass, leaving no more than a tiny ripple in the oceanic expanses of space and time.

For further exploration of contemporaneous influences on Lovecraft’s conception of cosmic horror, read my essay “Lovecraft, Lucretius, and Leonard’s Locomotive-God”: