This post is a companion to and continuation of “‘The Dread Contemplation of Infinity’: Some Thoughts on George M. Gould and Cosmic Horror Before Lovecraft,” Where that essay explores how Lovecraft’s conception of cosmic horror is best understood as a transvaluation of that which predominated from the 1880s through to the 1930s, this essay further explores Lovecraft’s developing conception of cosmic horror by focusing on another of Lovecraft’s under-recognized contemporary influences; namely, the American professor, poet, memoirist, and translator, William Ellery Leonard. This post is based on the conference paper, “From Beyond the Pleasure Principle: Freud, Lucretius, Lovecraft and The Locomotive-God,” which I presented as part of the Henry Armitage Symposium at NecronomiCon in August, 2019. Some of the material on Lucretius, Poe and Lovecraft in the first section is drawn from my essay “The Poet’s Nightmare: The Nature of Things According to Lovecraft.” If you want a more developed (and fully cited) version of that material, you’ll find it there.

Much of this material will be further developed in my in-progress book, tentatively titled Repulsive Influences, which provides a genealogy of cosmic horror while exploring the intersecting histories of Lucretius’s reception and the emergence of Anglophone gothic, horror and weird fiction.

LEONARD, LUCRETIUS AND LOVECRAFT

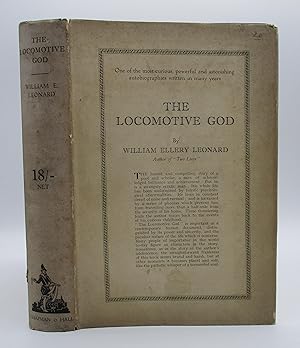

The first American to publish a complete English translation of Lucretius’s epic didactic poem De rerum natura was a professor of Classics at the University of Wisconsin named William Ellery Leonard (for an extensive study of Leonard’s life and work, see Neale Reinitz’s The Professor and the Locomotive-God.)

While his work is little read today, Leonard was among the most widely known American writers of his day, renowned both for his translations of Greek, Roman and Anglo-Saxon poetry and for his own poetry and his two memoirs, Two Lives and The Locomotive-God. The latter focuses entirely on the traumatic phobia that overshadowed Leonard’s life, and was widely read, both by psychologists (including Freud, whose correspondence with Leonard became part of the book) and general readers who were fascinated by Leonard’s minute, dramatically written analysis of his own “case.” Lovecraft thought highly of The Locomotive-God as a psycho-biographical memoir, and his curiosity regarding Leonard was no doubt intensified because, while it does not appear they ever met personally, they had only two degrees of separation via a number of members of Lovecraft’s Circle. Both men were friends with August Derleth, who was among Leonard’s pupils, and both also wrote appreciations of Frank Belknap Long’s writings

Quite apart from their shared social connections, Leonard’s writings bear importantly upon Lovecraft’s in ways that have, to my knowledge, never been critically explored. This essay focuses on two apertures through which Leonard’s work influenced Lovecraft’s developing conception of cosmic horror.

EDGAR POE AND LUCRETIAN COSMICISM

The first occurs in 1916, with the publication of Leonard’s translation and interpretations of Lucretius, On The Nature of Things. Leonard’s translation includes an end-note appended to the first instance of his use of the term Cosmos in translating part of Lucretius’ opening Hymn to Venus (DRN I 21). Leonard justifies his lexical choice by writing:

“In Greek, a technical term of that Stoic philosophy to which Lucretius was opposed; but in English fairly equivalent to the Epicurean “natura rerum,” through the associations of the word with Spencer’s “Cosmic Philosophy” and with modern materialism.”

Lucretius’s avoidance of the Greek word cosmos is informed by its teleological connotations, but Leonard suggests that these connotations need no longer apply given the term’s adoption by modern materialist thinkers. Lovecraft seems to have shared Leonard’s view in this respect, as his adoption of the term cosmicism to characterize his own philosophical sensibility suggests. Indeed, Lovecraft’s cosmic vision, following from Lucretius’s, is radically opposed to teleological assumptions about the natural world. S.T. Joshi writes:

“The central tenet in what Lovecraft called his “cosmic indifferentism” is mechanistic materialism. The term postulates two ontological hypotheses: 1) the universe is a “mechanism” governed by fixed laws (although these may not all be known to human beings) where all entity is inextricably connected causally; there can be no such thing as chance (hence no free will but instead an absolute determinism), since every incident is the inevitable outcome of countless ancillary and contributory events reaching back into infinity; 2) all entity is material, and there can be no other essence, whether it be “soul” or “spirit” or any other non-material substance. Lovecraft evolved these ideas through a lifelong study of ancient and modern philosophy, beginning with the Greek Atomists (Leucippus and Democritus), their followers Epicurus and Lucretius (whose belief in free will Lovecraft was forced to abandon), and such modern thinkers as Ernst Haeckel, Thomas Henry Huxley, Friedrich Nietzsche, Bertrand Russell, and George Santayana. Lovecraft’s metaphysical views seem to have solidified around 1919, when he read Haeckel’s The Riddle of the Universe (1899; English translation 1900) and Hugh Elliot’s Modern Science and Materialism (1919).”

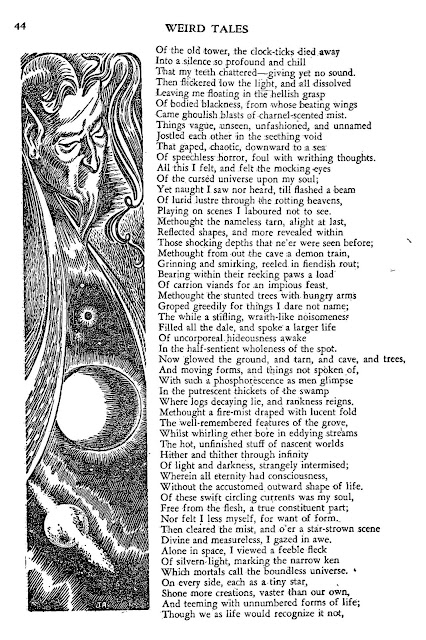

What effect Leonard’s translation and commentary may have had in shaping Lovecraft’s philosophical views is difficult to determine; in all likelihood, it was probably minor. The verbal and aesthetic parallels between Leonard’s translation and some of Lovecraft’s writings from this period, however, are intriguing, and particularly the “Aletheia Phrikodes” section of Lovecraft’s 1918 poem “The Poe-et’s Nightmare.” While the larger poem’s mock-epic structure is a love-letter from Lovecraft to his Augustan idol Alexander Pope, once called the “English Lucretius,” the “Aletheia Phrikodes” section is a cosmic stew in which blank verse Lucretian imitation is peppered with allusions to Edgar Allan Poe, beginning with the longer poem’s original title itself. One brief section serves to illustrate how Lovecraft twines Lucretius and Poe together:

Whilst whirling ether bore in eddying streams

The hot, unfinish’d stuff of nascent worlds

Hither and thither through infinity

Of light and darkness, strangely intermix’d;

Wherein all entity had consciousness,

Without th’ accustom’d outward shape of life.

Of these swift circling currents was my soul,

Free from the flesh, a true constituent part;

Nor felt I less myself, for want of form. (italics mine)

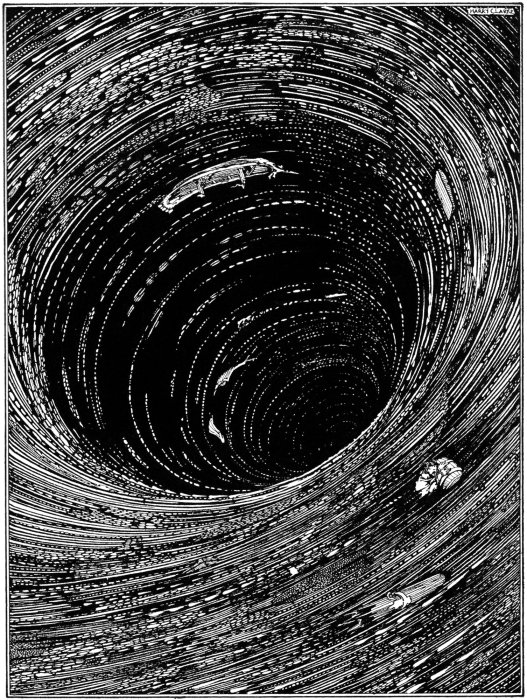

At once cosmogony and nekuia, The passage is part of an extended improvisation on both DRN V’s astronomic and meteorological passages and DRN III’s descriptions of the soul’s perishable materiality, but it also invokes Poe’s cosmic vision in early poems like “Al Aaraaf” and the cosmological prose poem, Eureka. In describing these fluctuating vortexes of metamorphic materiality as “eddying” streams, Lovecraft emphasizes the Poe-etic nature of this cosmic maelstrom.

That Lovecraft and Leonard shared an appreciation for Poe as cosmic visionary, a sort of American Lucretius, is certain. Such a view had been propounded by James A. Harrison, in his 1902 edition of Poe’s collected works; Harrison declared that “Both, in their poems, were passionate inconoclasts, idealists, dreamers of the speculative philosophies that looked into the causes of things; both set aside what they considered the degrading superstitions,” and were “refined materialists of an almost spiritual type,” which likely shaped both Lovecraft and Leonard’s associations between Lucretius and Poe.

Poe’s work is rife with eddying whirls and turbulent vortices, some of which spiral down into the oceanic depths, others of which whirl up and out through the unfolding universe of stars. Indeed, the spiral, in the dynamic form of the vortex, is the most pervasive and important motif in Poe’s writings, and engenders his aesthetics of the grotesque and arabesque, as Patricia Smith observes:

“The arabesque as Poe sees it is an attempt to suggest something kinetic — the motion toward unity — in a static medium; symbolically, it is always moving in the direction of the form-obliterating spiral. The man whirling about on Aetna resolves all he sees into a radical blur by means of his spin; the universe itself, in Eureka, collapses ultimately into a state of nihility. As in the Maelstrom, where all things “meet together at the bottom,” the final vision toward which the arabesque points is one in which unity is perceived, and it is impossible to distinguish one thing from another.”

Poe’s vortexes reflect his materialist metaphysics, which in turn derive from his own transformative reception of the classical atomist influences he shares with Lovecraft. Whether Lovecraft had read Leonard’s entire translation before drafting his poem is unclear, although he was certainly aware of its existence, and likely to have seen excerpts, as it was widely reviewed and noticed. That he had done so by 1922 is almost certain, as he mentions it approvingly in a letter to Lillian Clark, while noting that Derleth gifted a copy to Sonia Greene : “The generous little divvle is making presents on a large scale–Smith’s ‘Star Treader’ for me, an art book for Kid Belknap, & Leonard’s translation of Lucretius for Mrs. Greene–with whom he is trying to make up after his rudeness of last spring. Leonard is his English professor at the U. of Wis.–a scholar of note.”

Leonard’s phrasing reinforces the resemblance between this passage in DRN and Poe’s description of the whirlpool in “A Descent into the Maelstrom,” a tale that signals its own atomistic underpinnings by both its epigraphic reference to the Democritean δῑ́νη and its deliberate echo of Lucretius’s most famous passage, the “suave mari magno” description of a shipwreck that opens DRN II.

Leonard makes his Poe-tical homage even more evident a few pages later. Lucretius provides a naturalistic explanation for the absence of birds at Greek oracular sites including Cumae, an absence traditionally attributed to the awful supernatural influence of the gods. Instead, Lucretius explains that noxious gases that leak forth from the earth keep the birds away from such sites, which Leonard renders as “birdless tarns,” echoing Poe’s use of this antiquated term in describing the miasmic body of water into which the House of Usher falls. Leonard’s translation reads:

And such a spot there is

Within the walls of Athens, even there

On summit of Acropolis, beside

Fane of Tritonian Pallas bountiful,

Where never cawing crows can wing their course,

Not even when smoke the altars with good gifts,–

But evermore they flee—yet not from wrath

Of Pallas. (VI.280)

This echo of “The Raven” suggests, much as “The Poe’et’s Nightmare” does, Poe’s concatenation with Lucretius. Whether Lovecraft had read all of Leonard’s translation at this stage is unclear, but it nonetheless telling that both writers, soi-disant opponents of Poundian Modernism, returned to the Democritean δῑ́νη via such parallel descents.

LUCRETIUS, FREUD AND LEONARD’S LOCOMOTIVE-GOD

A decade before Leonard published his 1927 psycho-biographical account of his phobic obsessions, The Locomotive-God, his often- incapacitating agoraphobia was already reflected in the anxious intensity and alienation of his translations. In Leonard’s Lucretius, the descriptions of immensity and the void and the characterization of the monstrous Religio are particularly harrowing, as are his renditions of Grendel and the dragon in Beowulf, and each of these draws force from the compulsive power of Leonard’s growing anxiety.

Leonard’s phobia worsened considerably after 1918, in the wake of the catastrophic First World War. Near the opening of the book, Leonard writes:

“What was so poignantly my subconscious mind reveals itself, by the laws of our most common organic structure and development, as the mind of mankind. My own pain, my own struggle, has been, even to myself, a spectacle, a laboratory. And my findings differ in some ominous particulars from the previous record of poets and psychoanalysts. I have been persuaded […] by the desire to frustrate, by a neat and unexpected turn, those Demonic Forces which, as appearances go, have backed me for so many years against the wall. Beset by phobias, shell-shocked in a civilian war […] So out of very suffering and very failure I would create value: the value of a scientific document, the value of a work of art.”

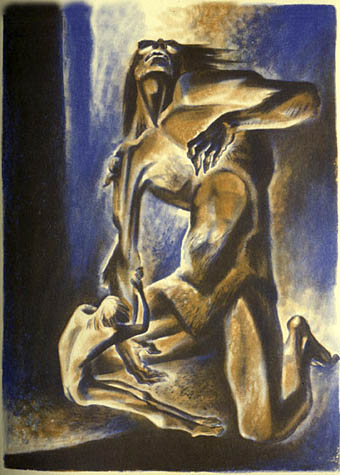

When atoms meet in the void through the clinamen, they can combine, or they can collide. Thus, attraction and repulsion are the fundamental principles of Epicurean physics. Lucretius, however, renders these in mythological terms derived primarily from Empedocles: Venus is a personification of attraction and combination, and Mars of repulsion and collision. In his post-war writings, especially Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Freud returns to such an Empedoclean mythic polarity with his conception of The Death Instinct as a counter to the Pleasure Principle.

It is a conception inspired, as W. Scott Poole emphasizes in his study of the Great War’s decisive influence on modern horror, by Freud’s horror at the catastrophic consequences of the war, consequences that Leonard also believed to have intensified his phobia, amplifying the power of the Locomotive-God over his mind and behaviour.

Leonard expresses this revelation in terms that are both explicitly Freudian, and explicitly Lucretian: “The “love-emotion” “could relive but not break the tension of the tangled mythology in which the subconscious in its deepest levels still believed…and still believes. The Locomotive-God won even against Aphrodite, goddess of manhood.”

The Locomotive-God traces Leonard’s trauma-induced phobic paralysis to a memory from his early childhood. As a two-year-old-child, he stood on a platform and watched a train pulling into the station. Disregarding his mother’s cries, he wandered to the edge of the tracks, until:

“It towers and lowers and grins in one awful metamorphosis, more grotesque than the most bizarre dreams of Greek mythology […] As It roars over the bridge […] scattering dust and strewn newspaper, the black circle of the boiler-front swells to the size of the round sky out of which the Thing now seems to have leaped upon me [….] this Aboriginal Monster. My eyeballs, transfixed in one stare, ache in their sockets.”

This terrifying memory would superimpose itself over, and come to stand for, every subsequent traumatic event Leonard would experience in his life. He writes,

“To me at a little more than two years, the Black Circle flashes a fiercely shaking Face of infinite menace, more hideous and hostile than Gorgon-shield or the squat demon in a Chinese temple, with gaping Jaws, flanked by bulging jowls, to swallow me down, to eat me alive—and the Thing is God […] God roaring from heaven to slay me for having disobeyed my mother and gone so close to the track.”

As an older child, Leonard would witness a cat struck by a train, which triggered the original trauma: “the cat got tangled up in the unseen web of my thought with the instrument of its death—the locomotive.” This led Leonard to claim that “terror is the supreme emotion of life, and it borrows its color from its Master, Death.”

As Leonard wrote his translation of Lucretius, “the Thing” would colour his descriptions not just of the immensities of the void, but also the description of Religio, Lucretius’s figuration of religion as a feminized embodiment of irrational compulsive power, that very force that Epicureanism is supposed to overcome. It is a figuration that resounds throughout Lovecraft’s non-fictional writings on atheism as clearly as his tales of malignant cults. Leonard speculates that “Much that we call Superstition is really Phobic Fear, not understood as such by the victim or those who gird at the victim; even as Phobic phenomenon have surely been a prime source, feeding the speculations and prepossessions of theologies pagan and Christian, of the belief in witchcraft.”

LOVECRAFT AND THE LOCOMOTIVE-GOD

The Locomotive-God’s influence on Lovecraft has gone largely unremarked, but it is hard to overstate its importance. More than any other single influence, it led Lovecraft further away from Gould’s predominant conception of cosmic horror, and helped cement for him the importance of the work on the nature of horror being done by psychologists including John B. Watson (on which see Dr. Sharon Packer’s essay) and Freudian psychoanalysis.

Leonard’s characterization of terror as “the supreme emotion of life” resonates powerfully with that with which Lovecraft begins his own 1927 essay on supernatural horror. Leonard’s frenetic description of the Locomotive-God, with its fusion of animal and vehicle, raw machinic power and perverse vitality, industrial modernity and primordial psychic dread, resonates powerfully with many of Lovecraft’s post-1929 monsters; most obviously, the shoggoths of 1931’s At the Mountains of Madness derive much of their terrifying imagery and potency from Leonard’s Locomotive-God.

In a 1929 letter to Derleth, Lovecraft acknowledged Leonard as “A character, & a figure of real importance in American letters.” By this point, he had read The Locomotive-God, and his letters praise the penetrating psychology of traumatic obsession that Leonard’s book offers. For example, a 1931 letter recommends it to Robert E. Howard as essential reading for anyone interested in psychobiography. As his recommendation to Howard reinforces, The Locomotive-God was crucial to Lovecraft’s conception of the power of atmosphere, the sine non qua of cosmic horror. Leonard’s provision of a mechanistic explanation for his own psychic trauma was especially valuable to Lovecraft as of 1931, as at this stage in his career he was explicitly looking for ways to generate “an atmosphere” of cosmic dread without turning to the superstitious tropes of classic supernatural horror. Leonard writes,

“The mechanism in its technique can be made clear to the reader. We start with a state of terror generated by past experience. The past experience itself remains in the subconscious. Its emotional effect, terror, bursts into consciousness. At times the emotional effect remains merely a diffused state of terror, in intensity running the whole scale from vague anxiety to intensest feel of impending death; and the agonized mind stands balked of any explanation whatever.”

Lovecraft later praises Leonard’s insight into his phobic experiences in a 1931 letter to Maurice Moe: “Unless one is steeled against the ascendancy of the capricious and meaningless subjective feelings, he is lost so far as the power of rational appraisal of the external world is concerned. Thus poor W. E. Leonard sees and feels things that aren’t there–and knows he does–yet continues to see and feel them just the same. That shows the power of irrational mood over rational perception.” It is precisely this power that, from 1927 on, Lovecraft, departing further from Gould’s nineteenth-century medico-theological concept, sees as the sine non qua of the best supernatural horror fiction, and, reinforcing his adoration of Poe, comes to term an “atmosphere” of “cosmic dread.”

.

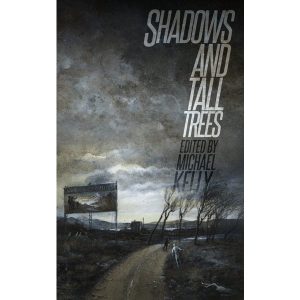

While the entire run of S&TT is excellent, and a must-read for those who enjoy quiet, creeping and artfully insidious horror and weirdness, this volume covers a wider range of voice and tone than its predecessors. Robert Levy, Simon Strantzas and Steve Rasnic Tem read excerpts from their contributions. It was Tem’s story, “The Erased,” that haunted me the most; it is a powerful study of the loss of self and world, a dispersion of identity and memory closely akin to dementia.

While the entire run of S&TT is excellent, and a must-read for those who enjoy quiet, creeping and artfully insidious horror and weirdness, this volume covers a wider range of voice and tone than its predecessors. Robert Levy, Simon Strantzas and Steve Rasnic Tem read excerpts from their contributions. It was Tem’s story, “The Erased,” that haunted me the most; it is a powerful study of the loss of self and world, a dispersion of identity and memory closely akin to dementia.