The car came before the night. It drove too fast along the dirt road, spitting gravel when it took the bend before Miller’s house. Miller watched from the porch and hefted his hunting rifle onto his lap.

The car slowed some once off the road, wobbling over the potholes that Miller’s pickup crossed every day without so much as a shudder. It crunched to a stop and the driver’s window came down.

“You Quentin Miller?”

Miller nodded. He was careful to nod very slowly and not move any other part of his body. Even his hand sat still on the rifle stock.

The car door opened and Miller watched as the driver climbed out. He hefted a smallish nylon camera bag onto his shoulder.

“My name is Sam Harvey. From the National Star. We spoke on the telephone.”

“Yes.” Miller’s throat was dry, and the word came out like a croak. Sam Harvey looked at Miller’s rifle.

“Been out hunting, Mr. Miller?”

Miller shook his head.

“Is everything all right?”

“For now.”

Sam Harvey took a careful step forward. He was heavy-set; not as big as Miller, but Miller thought that Harvey might be almost as strong. Miller felt a chill scurry up his back.

“I’d feel a lot more comfortable, Mr. Miller, if you’d put that rifle away before we speak.”

“Pay it no mind.” Miller still didn’t move. ” It’s not for you.”

Harvey shrugged, but Miller could tell he was not comfortable with the arrangement. “May I come up on the porch?”

“You may.”

Miller tensed as Harvey mounted the steps to the porch. Harvey came over and sat down on the bench, not too close to Miller. He reached into the breast pocket of his sports jacket. “I’m only taking out my tape recorder, Mr. Miller. I’d like to get this interview on tape, if I may?”

Miller felt himself relax. He smiled a thin little smile.

“You may, Mr. Harvey.”

Sam Harvey returned the smile. “Thank you.” He pressed two buttons on the tape recorder’s edge, and a red light flashed near the volume knob. He set the tape recorder down on the bench between them.

“Now Mr. Miller. You covered a great many of the details of your, shall we say, visitation, in your letters to my editor.”

Miller didn’t like the word visitation, but he didn’t say anything about it. Harvey continued.

“And I have to say that the photographs you provided were very convincing. You took them yourself, didn’t you?”

Miller had. He had used up all of a disk of film back in the barn. Harvey reached into his breast pocket again and took out a little envelope. He opened it up and took out a stack of photographs. Miller peered at them. They were his pictures, but they were bigger, and grainier. The National Star had made copies, Miller realized. Kept the originals at the office.

“In a few minutes, I’d like you to show me where this happened,” said Harvey. “But first, could you describe, in your own words, what happened the night of your `visitation?'”

Miller exhaled noisily. “Don’t like that word,” he said. Harvey looked worried for only an instant before regaining his composure. “There was no vis-it-ation like you put it. Simple thing was, my fears came to life.”

“But Mr. Miller, in your letter you described fabulous lights; `zooming through the cosmos’ were your words–”

“I wrote that letter but two days after my fears came to life. Maybe in those two days what happened seemed like a visitation. But now I don’t think that’s what it was. I’ve done some thinking back on my days, and I think those lights were a …” Miller struggled for the word.

“Manifestation?”

“Yeah. A manifestation. Of my fears. Headlights. From automobiles. Almost killed by one when I’s a boy.”

Sam Harvey was frowning now. “So let me see if I understand correctly. You think that all of the things you’ve claimed happened to you are a figment of your imagination?”

“Nosir. I think they’re a manifestation of my imagination. I can show you the scorch marks in the back field, and the situation in my barn right now if you’d like.”

“You mean the pig.”

Miller nodded.

“Well, under the circumstances maybe we’d better have a look. Shall we talk as we walk, Mr. Miller?”

“Suits me.” Miller waited for Harvey to stand up before he got up himself. The two walked around in back of the house. Harvey held his nose as they hurried past the barn, and Miller let the journalist open the gate to the pasture.

“Helluva stink,” said Harvey. Miller said nothing. They climbed over a rise, and below them Miller’s pasture spread the length of a valley, effectively as far as the horizon. The burnt carcasses of cattle were interspersed with big black patches of charred grass, like giant hoof-prints.

“The lights went away before I knew what to do,” said Miller. “Being as they’re manifestations of my fears I expect them back before long.”

Harvey was talking into his tape recorder in a voice too low for Miller to hear. Miller wondered if Harvey would want to take any photographs, but the sun was almost gone.

“You know,” said Harvey, finally loud enough for Miller to hear, “I’ve been to maybe six sites with physical evidence like this, and it always comes after what UFO people would call a `close encounter.’ I wouldn’t be so quick to dismiss this as imagination. How many cattle did you lose?”

“Sixteen.”

“Jesus. Was that the herd?”

“Pretty near.”

Harvey seemed to glow in the dying light. “Mr. Miller, you’ve done the right thing in writing to us. I think you’ve got a real find, here. It was smart of you not to go to the Midnight Globe or one of those other rags.”

Miller grunted. He didn’t tell Sam Harvey how many newspapers he’d considered. Every one he could find under the canning in his wife’s pantry, and some of those had been doozies.

Harvey opened his bag and took out a camera. It had an expensive-looking lens, and Harvey twisted it as he looked through the viewfinder. He put it away without clicking the shutter once.

“Not enough light,” said Harvey apologetically. “I’ll come back tomorrow for this, though.”

Miller grunted. “Let’s look in the barn,” he said. “If you’re up to it.”

“Ah. The pig.” The two started back. Harvey held the tape recorder close to Miller’s face. “While we’re on our way, could you tell me what happened with that?”

“Met the pig the day after the lights. I was still getting my thoughts together on the subject. I’d already begun my letter to your editor. I was setting at the kitchen table when I heard the squealing.”

Harvey put a hand on the gate as they passed through it. “How did the squealing sound to you?”

“Loud.” Miller brushed Harvey aside and shut the gate himself. “Went out to take a look. Over there.” Miller pointed with the rifle barrel at the pig pen. It was smashed so the wood was white along the wall where the pig had broken through.

Harvey let out a low whistle.

“When I was a little ‘un, pigs got loose. Took me ‘n my dad better part of the day to gather them all up, and the last one we didn’t get until well into the night. I tracked him down into the back forty, and by then it was pretty dark. All I can remember is screaming like a baby for my daddy, and seeing those red little pig eyes staring at me from every shadow.”

“What happened at the pig pen?”

“Same thing. Same pig, only twelve times bigger and a hundred times meaner.” Miller looked at Harvey meaningfully. “Manifestation of my fears,” he said. Sam Harvey pursed his lips and nodded.

“So what happened?”

“Pig came at me, that’s what.”

“And?”

“I ran into the barn. Pig followed.”

“And?”

They were at the barn door now, and instead of answering, Miller removed the latch and pulled the door open. A cloud of flies buzzed forward as the door swung free and the smell came out. Harvey gagged and swatted over his forehead with his tape recorder. Even Miller made a face. The pig had gotten ripe.

It lay sprawled across the barn’s width, ass-end towards the door and knife-edged bristles gleaming in the last of the sunlight. At the far end of the barn, tusks curled up over its head, higher than the handle of the pitch-fork Miller had embedded in the monster’s skull. Its belly had bloated and its bruised-purple hide pressed like a balloon between the rungs of the ladder to the hayloft.

Sam Harvey just looked. Finally Miller motioned to the pitchfork.

“That’s where I killed it,” he said.

#

They shut the barn door and went back to the house. Miller invited Harvey inside. It was past supper, but Miller didn’t see any harm in some whiskey before lights-out. And Harvey said he had more questions.

“I’d like a list of all the things that have happened,” said Harvey. “All your `manifestations.'”

Miller didn’t tell him all of them. He did mention the daddy longlegs spider that had grown sixty times its original size and tried to crawl down Miller’s throat one night. And how the barn cat had had to go once it grew a scorpion tail and dragonfly wings and began to hover outside windows after dark. There was a hole from a shotgun blast in the plaster at the back of Miller’s bedroom closet, and another in the far wall of the bathroom, where Miller had finally cornered a bogeyman the night before last.

“How many more do you figure?” asked Sam Harvey finally.

Miller shrugged. “Who knows? How many fears does a man carry through his life?”

“I couldn’t say. Do you always keep that rifle so handy?”

The rifle leaned against the kitchen table beside Miller. “I’d be fool not to.”

“And that’s how you protect yourself. Against your manifestations.” Harvey motioned at it with his mug. “Your fears.”

“This is the downstairs gun. Got a twelve-gauge upstairs.” Miller patted the stock of the rifle. “You live on a farm in these parts, that’s how you take care of things. Like fixin’ a fox who got into the henhouse. Only one way.”

Harvey stopped a grin. “Perfect.” He only mouthed the word, but Miller read his lips and Harvey reddened when he looked up and saw Miller’s face. To cover his embarrassment, Harvey jumped into another question. “Do you keep all of the manifestations of your fears around when you’re finished? Like the pig in the barn?”

“‘Till I figure what to do with them.” Miller was getting impatient. He knew the Star printed a lot of fool stories, but not as fool as some of those papers did. But for all the hopes he had for the esteemed journal, the Star’s Sam Harvey was as slow on the uptake as any city boy. “You got any ideas what I should do with half a ton of pig?”

Harvey nodded, and didn’t smile this time. “You married, Mr. Miller?”

Miller bridled. “I suppose.”

“I see.” Harvey squinted at Miller. “Your wife staying with friends while this is going on?”

“I don’t know where my wife and son are staying, Mr. Harvey.” Miller felt his stomach knot. “They’re just not staying here anymore.”

Can you blame them? Harvey seemed to ask with his eyes.

“Ah,” Harvey said aloud. “Didn’t mean to pry, Mr. Miller.”

“No mention of it.”

“One more question, Mr. Miller.” Harvey swirled the whiskey at the bottom of his mug. He didn’t meet Miller’s eye. “Have you ever seen one of these manifestations appear?”

Miller frowned. “Don’t follow you.”

“What I mean is, you’ve seen the end result of these manifestations — UFO lights, a giant pig, a giant spider, a cat with wings… a bogeyman. Have you ever seen one come into the world? The moment it transferred from… your subconscious to reality?”

Miller thought a moment. “Nope,” he finally said.

Harvey smiled into his mug. “It would be interesting to see. It might answer a lot of questions.”

Miller supposed one could look at it that way.

Sam Harvey took a last swill from his mug and stood up.

“Well, Mr. Miller, it’s getting dark, and I’d better be getting back to Wingham. I’d like to come back in the morning if I may, and take some photographs when the light’s a little better.”

“Whatever suits.” Miller stood up to show Harvey out, but Harvey waved him down.

“I can find my way. And don’t worry about me, Mr. Miller. They’re your manifestations, not mine.”

Miller thought about following anyway, but decided not to. He sat down and watched Sam Harvey straighten his coat and turn to leave.

The screen door clattered shut and the reporter stepped off into the night.

#

Miller didn’t move. He had the rifle in his lap again, and he’d taken his nearly-empty box of ammunition out of the cutlery drawer and put it on the table in front of him. Miller sat as still as he could.

Outside, Sam Harvey crunched across the gravel of the driveway and opened the car door. Miller could hear the car door shut more clearly — Harvey had a good arm on him, that was a certainty — and Miller waited for the engine to start. It didn’t.

Miller sat still. There were no sounds at all. None but Miller’s own heartbeat, and the hushed rasp of his breathing. Miller wished he could quiet those too. Then he might hear what was happening outside.

Should have gone with him.

What was it Harvey had said? It might answer some questions.

Miller picked up the box of ammunition and put it in his jacket pocket. He stood up, took the flashlight off its hook over the refrigerator, and went outside. He didn’t let himself tremble.

Harvey’s car was dark and quiet in the drive. When Miller speared it with the flashlight beam, the light only bounced back off the windshield. Inside was inscrutable.

Flies danced through the light in a swarm, and as Miller stepped closer to the car their buzz became audible.

But there was another sound, underneath the buzzing. Miller strained to hear.

The car was starting to thump.

Miller took the remaining two steps to the driver door and, holding the flashlight close to the glass so it couldn’t reflect, aimed it inside.

Sam Harvey looked out at him. Miller wanted to run back to the house, but he held the flashlight steady. Answer some questions. Miller watched.

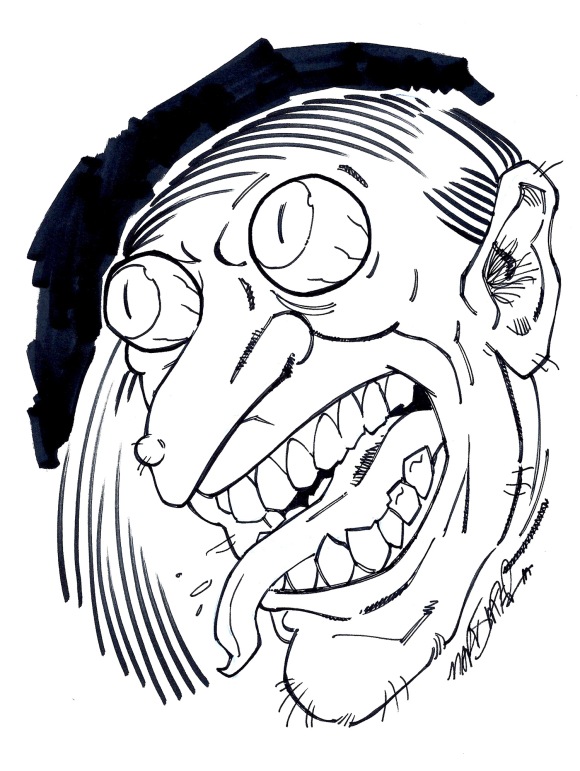

Harvey’s face had started to move. His chin, which had been broad and full like a man’s should be, was pulling thin and pointed. The baby fat in the man’s cheeks was draining away, replaced by lines and crevasses and shadowy pockets around bone. As Miller watched, Sam Harvey’s short black hair started to twist and grow. His whole head spasmed for an instant, and his neck extended seven more inches from his shoulders. It twisted like a snake, and Harvey’s forehead hit the windshield with a muted thud! The skin that pressed against the glass was patched with green.

“The Wicked Witch of the West.”

Recollections of balls of technicolour fire and flying broomsticks and terrible monkeys with batwings came unbidden to Miller.

The thumping grew louder, and when Miller looked down to its source he could see that it was caused by Harvey’s attempts to open the door. His fingers were growing so he couldn’t get his hand around the handle, and now the hand was so big that the noise of those attempts was formidable. Each finger was the length of Miller’s forearm, and attached to it was a razor-steel talon extending another four inches.

Harvey found Miller with eyes that had turned yellow around their cat-slit irises. His lips twitched above growing teeth and tapering tongue, and when he spoke it was in a witch’s cackle:

“Help me Quentin!”

Miller stepped back and raised the rifle. He wished he’d taken the time to carve crosses in the bullets’ tips. It might take a hollow-point this night.

Sam Harvey’s car was beginning to shake back and forth on its suspension as Harvey grew larger within. The cackling shook leaves overhead.

“Quentin! Mister Miller! Make it stop!”

And then it did stop. The car reached equilibrium, the cackling silenced, and only the faint rustle of leaves on this quiet night showed anything out of the ordinary. Miller wasn’t fooled, though.

A low moan started up. Miller shone the flashlight across the car, and stopped at the front windshield. Its edges were pulling loose from the rubber seals. Miller stepped back a few more steps.

The glass escaped with a sucking sound. Long, dark arms lifted it and flung it towards the barn. It shattered unseen in the shadows.

The witch unfolded herself from the front of the car.

Miller knew he should shoot, but something stopped him. Sam Harvey. This was Sam Harvey. Miller let the thing finish.

It must have been nine feet tall on the ground, and standing on the hood of the car its giant head brushed the leaves. The witch’s eyes glowed bright yellow in the flashlight’s glare. They fixed on Miller above a terrible grin. The witch was all but naked, holding only the torn rags of Harvey’s sports jacket that barely covered its long, tube-like breasts. Thick black hairs writhed around its areolae, and at its groin.

The witch’s thin arms lifted, and on a new breeze she rose into the air.

Miller dropped the flashlight and fired twice. The first shot whistled off into the trees, but the second one must have hit. He heard a shriek like tires before a highway wreck, and the witch descended out of the night.

He saw her by her eyes, and the light they cast on her gleaming talons. Miller lifted the rifle and aimed between those eyes.

The bullet missed and struck the witch’s chest. A breast exploded in a rain of soured milk, and the impact threw her flight askance. A talon tore away the shoulder of Miller’s jacket, and he felt the remaining denim fill with his blood.

The witch landed ten feet off, in the direction of the barn. Miller stumbled back towards the light of his porch as the hag tottered upright on her twig legs.

“There’s nowhere to run, My Pretty!” The witch reached over its shoulder, and a black fabric appeared there, like a splotch of ink. The fabric spread, covering her single dangling teat. Bloody milk still streamed from the other and puddled at her enormous feet as the robe stretched down.

Miller stuffed three more bullets into the magazine and slid the action shut. He almost tripped over the low steps as the hag moved forward.

“When I was a little ‘un,” he told the approaching monster, “my mommy took me to see The Wizard of Oz. Told me it had all the songs she used to sing me to sleep by; told me about the Emerald City and the ruby slippers and the poppy field and the Munchkins. Didn’t tell about you, though.”

The witch cackled his name across the yard: “Quentin!”

There was none of Sam Harvey in the witch’s voice, although Miller listened for it.

Miller raised the rifle to his shoulder, and the witch hesitated. Her eyes glimmered yellow through long, twisted eyebrows.

“You can’t run away, Quentin Miller.”

“No.” Miller’s hands had been shaking, but the word steadied them. He’d done all his trembling as a boy, in the nights after he’d faced that movie. He wasn’t a boy anymore. “I can’t run away,” he told the witch.

The fabric stopped growing. It was a robe now, blacker than the night around it and tattered at the hemline, so that it seemed to throw off November-bare branches in the growing breeze. The witch raised her arms, and in one of her claw hands there was a broomstick, as long as Miller was tall. As long as the broom had been in the movie, to little Quentin Miller’s wide little eyes. The witch took to the air.

Miller squeezed the trigger, worked the lever, squeezed again, slid another round into the chamber and fired a third time. Gunfire echoed and thundered through Miller’s farm.

The first bullet caught the witch through her knee, and because it was so thin the limb severed there in a burst of bone and ichor. The second hit the stomach, sending spaghetti-thin intestine trailing as she flew towards him. The third bullet went high, and found the witch’s skull just above one of her brilliant yellow eyes.

Miller leapt back just in time to avoid her flailing, senseless form as it crashed into the porch.

#

Since his fears had begun to take a life of their own, it had become Miller’s custom to wait until the morning to deal with the previous night’s carnage. Sometimes, as in the case of the pig and the cattle, he could not bring himself to deal with them at all.

But Miller cleaned up the witch as soon as he had dressed his wound and swallowed a shot of whiskey for the pain. He took an old sheet and, folding the birdlike limbs in on themselves, he wrapped the creature up and carried it to the cellar. It wasn’t heavy and even with his wound the most difficult part was negotiating the long arms and single leg around corners. Flies made ticking sounds against the single sixty-watt bulb that lit Miller’s cellar.

He set the Wicked Witch of the West near the back, next to the cat that had flown on dragonfly wings and the daddy longlegs, whose twelve-inch legs had been contorted over its tennis-ball-sized body into an old canning jar. He stood looking at the three fears sitting there, and tried to imagine them as they had been. He found that he couldn’t; not even the reporter, whose name had already faded from Miller’s memory.

Finally, Miller turned towards the stairs. Before he left the cellar, he paused at two more fears: the corpse of the squat vulture thing he had brought down with the wood-axe three days ago; and the tiny, drying bogeyman, shot dead in the bathroom the night before last.

Miller looked at the two of them, and his lips pursed bitterly. There had been a question today; he remembered that much. Where do they come from, Mister Miller? someone had asked.

Where do they come from indeed? Miller stopped tears before they had a chance to start. He knelt close to the manifestations and studied them for what seemed like a very long time.

And then, because he could think of nothing better, Quentin Miller kissed his wife and son and went to sleep.

*

© 2014 by David Nickle. “Manifestations” first appeared in Northern Frights Volume 1 (1992).

Original illustrations © 2014 by Mark Slater.

David Nickle is the Stoker-award winning author of, most recently, The ‘Geisters and Knife Fight and Other Struggles.

Mark Slater is a Toronto-based illustrator and graphic designer.